By Ian A Ingram

Terms used:

- Sunrise and sunset positions:

- MSSR: Mid-summer sunrise.

- EQSR: Equinox sunrise

- MWSR: Mid-winter sunrise

- MWSS: Mid-winter sunset

- EQSS: Equinox sunset

- MSSS: Mid-summer sunset

- Equinox: Throughout the year, the Sun appears to travel northward and southward because of the Earth’s tilt of 23.3°. The Sun sits at Due East and Due West twice in a year on the Julian calendar dates of March 22nd and September 22nd.

- Azimuth: the angle between True North (0°) and a distant point, expressed in degrees, minutes and seconds.

- Ecliptic: a circle on the celestial sphere representing the sun’s apparent track during the year.

All stated elevations are in feet or metres above sea level, defined by usually Ordnance Survey concrete markers (trig. points).

Introduction

The question of why megalithic structures are situated where they are is an area of research that is developing and is open to more detailed examination. The surrounding landscape of each megalithic structure is obviously its immediate context. There, a trained or sensitive eye can find evidence for the builders’ concerns and decisions. Very often the local horizon is combined with sunrise and sunset events, weaving the circle’s structure into the landscape and the heavens. This article will demonstrate that the local topographies of two megalithic structures on each side of the Irish Sea were extended at scale as part of a cohesive network of sites aimed at linking widely spread communities.

Ballynoe and Swinside stone circles: descriptions

The megalithic stone circles of Ballynoe and Swinside are situated on opposite sides of the Irish Sea. Ballynoe is a small village south-west of Downpatrick and approximately seven miles directly west of the County Down coastline. Swinside is a slightly remote circle in Cumbria, approximately 10 miles east of the small coastal town of Bootle. The circle is reached by road from Millom or Broughton in Furness.

There are no definite datings for the construction of the two circles; they were probably built in what is now recognised as the main megalith period of 2500-1800 BCE. Similarities are evident in the arrangements of stones; both circles have almost the same number of stones that are placed closely together; generally, both have taller stones at north and south. Both circles have received relatively little archaeological investigation.

The circles are large. Ballynoe has a diameter of about 106 feet, 32 metres, with 61 stones forming the circle, reaching heights of 1.8 metres. Additionally, in its interior, there are 25 stones positioned in an arc around a large cairn of uncertain date. There are outlying stones in the surrounding fields, with a block-like standing stone 122m west of the circle. The central cairn at Ballynoe was excavated in 1937-8, but no further investigations have been carried out near the circle stones, nor on its many outliers.

Swinside has a smaller diameter of 93.7 feet, 28.56 metres and has 55 stones. The tallest stands at 2.3 metres at the north of the circle. At Swinside, a brief excavation in 1901 opened two trenches, but revealed little about the site (Burl 2005). There have been no further excavations.

Ballynoe and Swinside stone circles: parallels

There are clear similarities in their respective local topographies. Each circle is in a gently sloping valley near a stream flowing north to south. At Ballynoe circle, the ground slopes down at the south and west. To its east is the higher ground of Carney Hill, at 200 feet, 58 metres, the highest point between the circle and the Irish Sea. At Swinside circle the ground slopes down at the south and east. The highest ground is to the west at Swinside Fell, which rises to 1233 feet, 376m. These similarities are striking: each location is a mirror-version of its neighbour across the Irish Sea. Notably, each circle has the high ground between it and the Irish Sea. The significance of these higher hills and fells will be explored in depth below.

The architectural details of the circles show parallels. Professor Aubrey Burl writes on the circles’ similarities:

[Ballynoe]…Is reminiscent of the very large stone rings of Cumbria, the meeting places for dispersed groups of people. Ballynoe’s low-lying position by a river is in agreement with this, as is its architecture.

[At Ballynoe] All these features: the large diameter, many stones, the north-south line, the entrance, the outliers, are ‘Cumbrian’ in style, very like Swinside 100 miles ESE…. It is likely, therefore, that Ballynoe is one of the earlier circles (Burl 1976, p.238).

In the Neolithic period, there is considerable evidence to show that communities on each side of the Irish Sea were closely connected. The circles amplify this. Sea routes were travelled. Possibly from 4000 BCE onwards, domestic animals were introduced to Ireland alongside arable crops such as barley (Wikipedia 2025). There are clear influences in pottery styles; dolerite axes imported from Cumbria and the Preseli hills in Wales have been found in Co. Antrim.

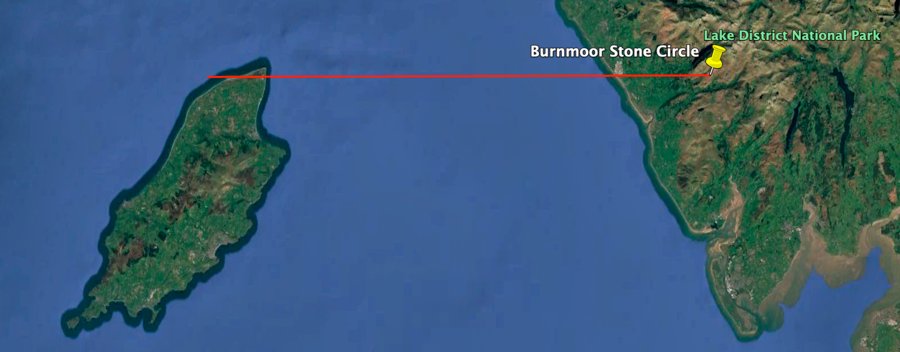

Ballynoe and Swinside stone circles: co-ordinating their geographic positions

Unfortunately, Burl’s ‘ESE’ direction is mistaken. The latitude of Ballynoe is 54° 17’ 27”N /54.29070°N and the latitude of Swinside is 54°16’57”/ 54.28245 N. Therefore the two circles are sited, almost exactly, on the same latitude. The centres of the respective circles are apart by only 0.00825° of latitude. Since a degree of latitude at 54°N = 365,173.03 feet, their separation north to south by 3,012.68 feet, 0.918261 kilometres. Over a distance of nearly 100 miles, 160 kilometres, they therefore sit relative to each other almost exactly at the cardinal compass points of East and West. The following will show that this is unlikely to be coincidental as they are part of a network of megalithic monuments around the Irish Sea whose locations are determined within a consistent systematic framework.

| Distances in miles and kilometres | Ballynoe to Swinside |

| Statute Miles (spherical Earth) | 98.738 |

| Kilometres (spherical Earth) | 158.903 |

The distance between the circles is such that, viewed from their respective adjacent hills, across the Irish Sea, there is no possibility of them being inter-visible. To align the circles, a mid-point was needed. That point is near to the highest mountain on the Isle of Man: Snaefell, 2037.4 feet, 621 metres. The island and its peak are visible from the respective higher grounds near to the circles. Snaefell sits, almost, on the same line of latitude as the two circles. But this alignment does not explain how the circles were positioned so accurately on the same latitude. A problem also is that mountain peaks were not used primarily by the circles’ builders for tracking the sun. They needed an horizon that was less elevated and more horizontal. Additionally, Snaefell is too far south for a precise east/west alignment between the circles.

Comparison of coordinates between Ballynoe / Snaefell / Swinside

| Latitude | Longitude | |

| Snaefell summit | 54°15’48” / 54.26324N | 4°27’43”W / -4.46157 |

| Ballynoe | 54°17’27” / 54.290833 N | 5°43’34” W / -5.725880 |

| Swinside | 54°16’57” / 54.28245 N | 3°16’21” W / -3.27386 |

Snaefell summit is close to the median point between the two circles.

| Distance, miles and kilometres | From Ballynoe to Snaefell | From Swinside to Snaefell |

| Statute miles (spherical Earth) | 51.039 | 48.753 |

| Kilometres (spherical Earth) | 82.14 | 78.46 |

In all probability the Isle of Man was a significant geographic and symbolic marker for the communities on the shores of the Irish Sea. Edward Bernbaum identifies ten characteristics of ‘mountain’ that can pertain in any quantity to a local culture. The height of a mountain is its first quality:

Poised above the surrounding landscape, set in a fluid realm of drifting clouds and flowing sky, its summit appears to float in another world, higher and more perfect than the one in which we dwell (Bernbaum, cited in Wikipedia 2025).

Viewed from the coasts of the Irish Sea, this is a very apt description of the island. His second characteristic of the mountain as a centre might also typify Snaefell:

the center appears in its most comprehensive form as a central axis linking together the three levels of the cosmos – heaven, earth, and hell or underworld. As the link between heaven earth, and hell, it acts as a conduit of power, the place where sacred energies, both divine and demonic, spew into the world of human existence (Bernbaum, cited in Wikipedia 2025).

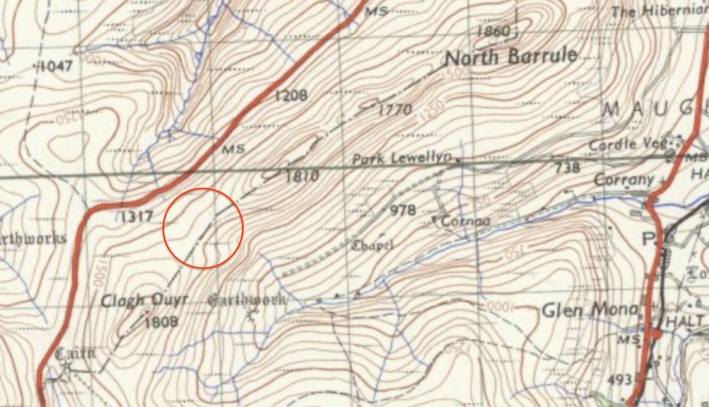

Because of the Earth’s curvature the profile of the Isle of Man, seen from the adjacent coasts, appears slightly below the horizon. To the north of Snaefell there is a col – a dip in the height of the hillsides – between North Barrule (565m ) and Clagh Ouyr (550m ). Its location is at 54° 16’ 39”N, very close to the respective latitudes of the circles. The elevation of the col is 472m, about 80 metres, below the adjacent summits. The col is therefore visible, just above the sea horizon.

On two days of the year, the col provided the means to coordinate the latitude of the respective circles. On these days the sun rises due East and sets due West. They are the Equinox dates in the Julian calendar of March 22nd and September 22nd . Along the same line of latitude, the col viewed from the west is the place of Equinox sunrise. Likewise, viewed from the east, the col is the place of Equinox sunset. Each circle needed high observation points with unobstructed sightlines to the col.

At Ballynoe, Carney Hill provided the observation point. From the circle, the ground rises gradually to the hill’s summit at 200 feet, 54m. Its latitude is 54° 17’ 24”N. The hill fulfils a key function since it is the highest point between the circle and the Irish coastline to the east. It overlooks an extensive low-lying area- a landscape in which the maximum elevation is about 100 feet, 30 metres, The Isle of Man is thus visible from the hill’s summit. A curiously shaped and positioned standing stone to the west of the circle may have provided a clear sightline to the summit.1

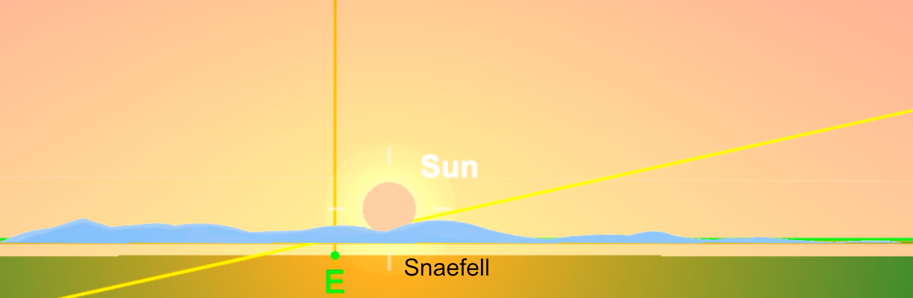

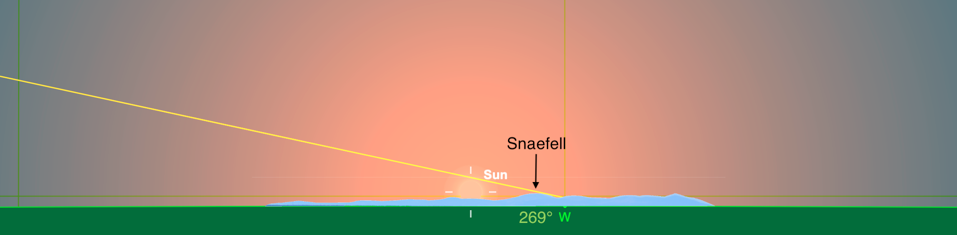

Viewed from the summit of Carney Hill, the uplands of the Isle of Man are visible, with the elevation of Snaefell summit at 0° 16’ 36” (because of the Earth’s curvature, the lower 300 feet, 100m, of the island are below the horizon). On the day of Equinox, directly East, the sun shows its first glimmer over the hill of North Barrule (to the north of Snaefell) then the full orb of the sun appears in the col between that hill and the summit of Snaefell. The sun rakes the northern flank of Snaefell as it rises.

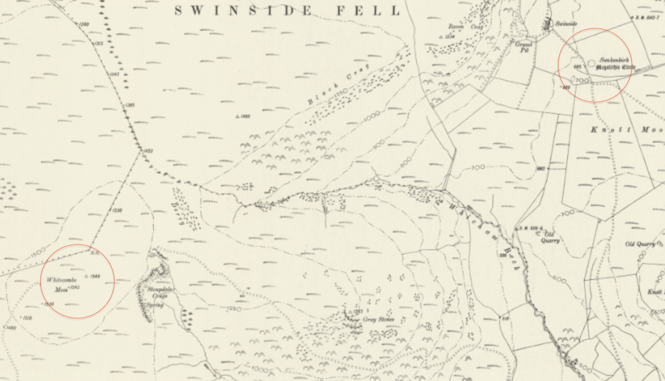

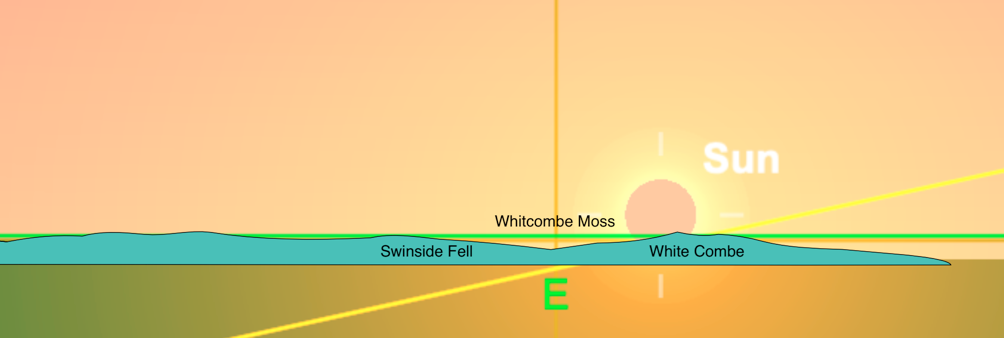

At Swinside, the fells to the west provide the observation point from which the Isle of Man and the circle are similarly intervisible. Approximately 1.3 miles WSW of the circle, there is a watershed at Whitcombe Moss, 54° 16’ 30”N, 3° 18’ 16”W. This proposed viewing point is marked by an OS trig point at 1548 feet, 472 metres. There is an uninterrupted view westwards to the Irish Sea and to the Isle of Man and eastwards to Swinside circle.. The area around Whitcombe Moss has considerable prehistoric community activity. West of the the watershed are several Neolithic and Bronze Age cairns and field systems dating from 3000-1500 BCE. We shall see that Whitcombe Moss has further significance in the network of neolithic sites around the Irish Sea.

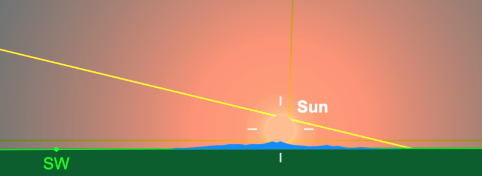

The sun sets into the southern flank of Snaefell and may illuminate a ‘last glimmer’ as it sinks into the col, due west, on the northern flank of Snaefell. This is the same col on which the equinox sunrise is seen from Carney Hill. The yellow line is the ecliptic. The observation points at each circle are below:

Summary

Comparison of coordinates between Carney Hill / Col / Whitcombe Moss

| Location | Latitude | Longitude |

| Carney Hill | 54°17’24”N | 5°42’40” W |

| Coll | 54°16’39”N | 4°25’50”W |

| Whitcombe Moss | 54°16’30”N | 3°18’ 16”W |

| Difference maximum Lat / Long | 00°00’ 54” | 2°24’24” |

| From | To | Bearing |

| Carney Hill | Col | 90.96° (East) |

| Whitcombe Moss | Col | 270.05° (West) |

Evidence of equinox markers at the stone circles

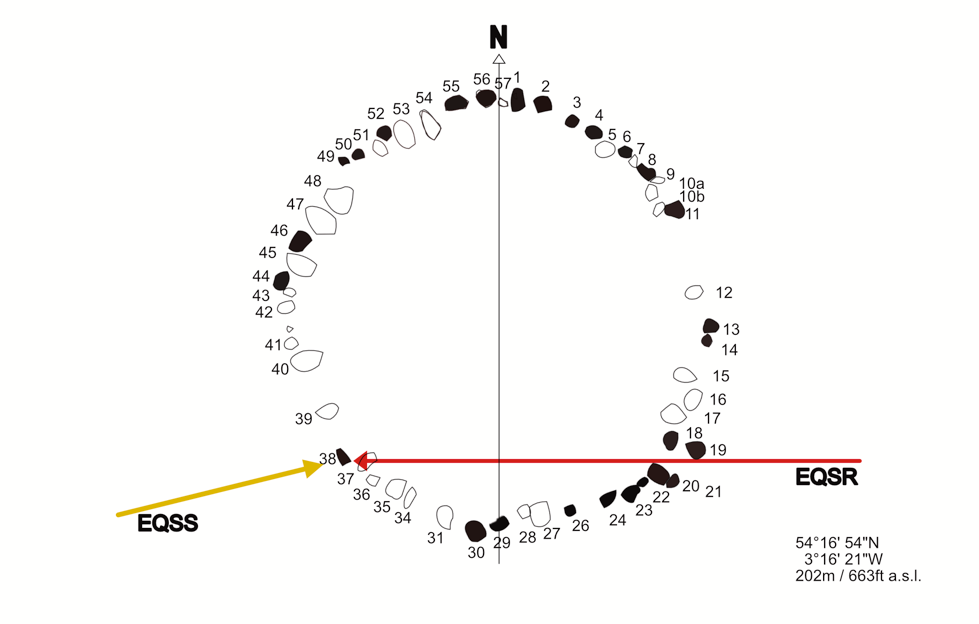

1. Ballynoe circle, equinox sunset (EQSS).

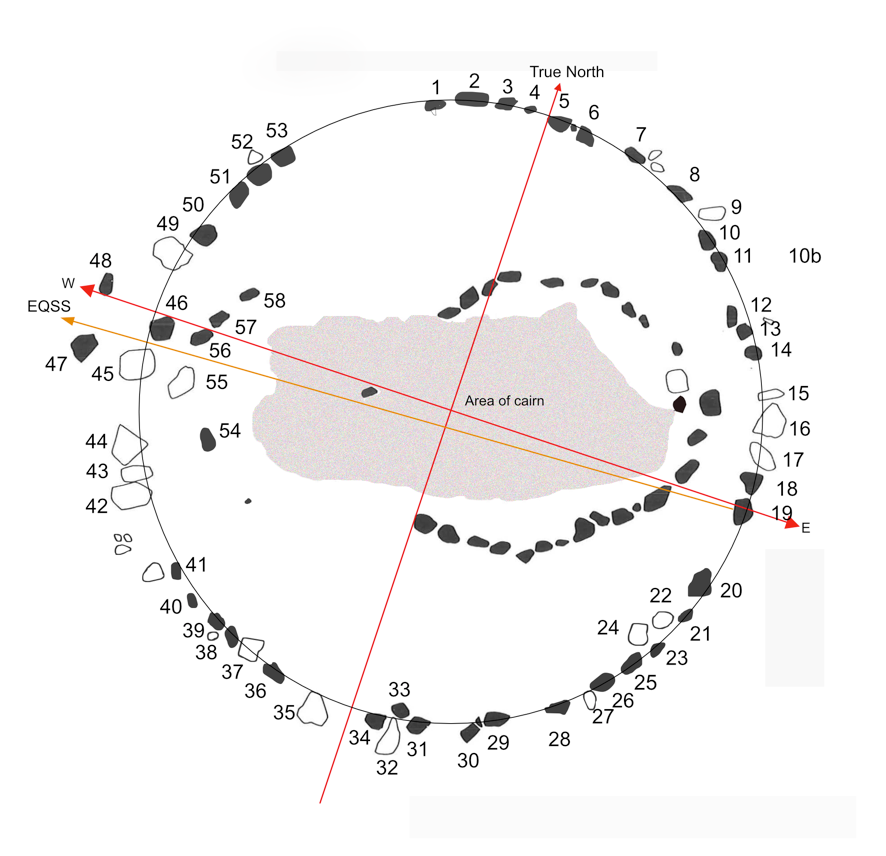

True north at the circle was established on my visit site in May 2025 with a calibrated compass, correct to 0.3°.

The sight lines across the circle to the cardinal points are slightly interrupted by the height of the cairn at 1-1.4 metres. Perhaps this is an indication that the cairn, whose date is not presently known, may have been inserted into the circle after its construction. On the plan, the east/west axis of the circle can be seen extending from stone 19, the circle’s most easterly stone, to stone 48. Stones 54 to 58 are smaller kerb stones related to the central cairn.

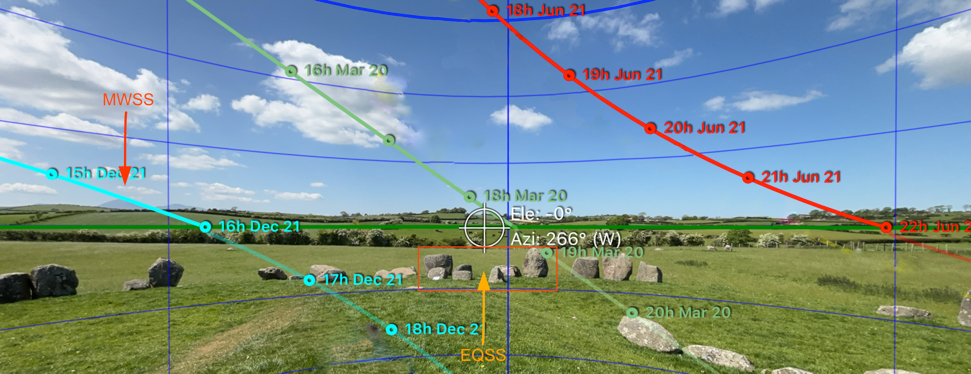

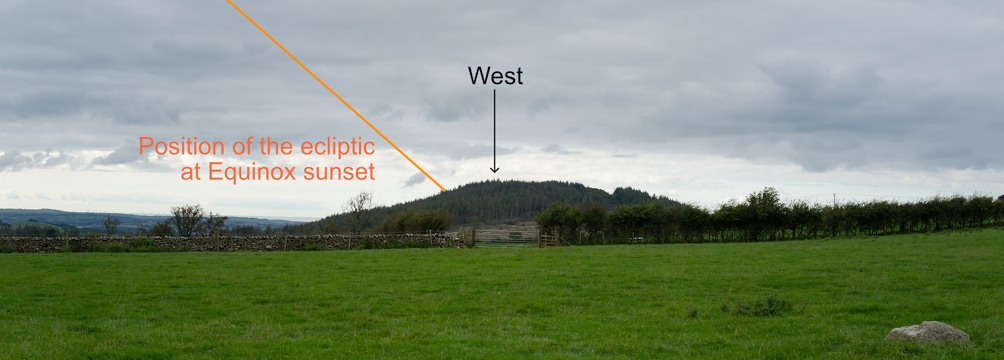

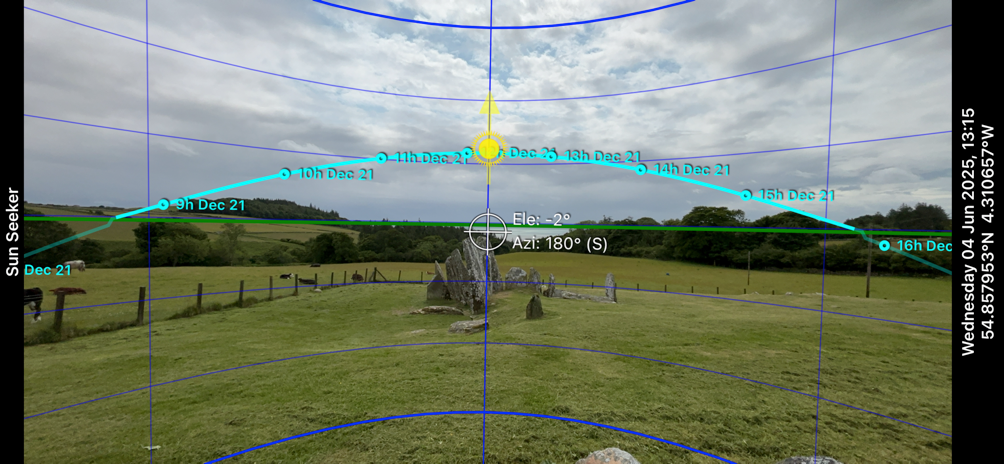

The circle stones 45, 46, 47 and 48 form an ‘entrance’ or ‘gateway’ below the setting equinox sun. Using the Sun Seeker app (image below) to determine a sunset position seen from stone 19 shows the equinox sunset full disk to be at an azimuth of 266° as it sits on the horizontal horizon, which has an elevation of approximately 2° from the circle. The equinox sunset (EQSS) alignment is represented by the orange arrow on the photograph below.

The Sun Seeker app illustrates the position of the ecliptic (the track of the Sun) throughout the year. Equinox is represented by the green line. The quadrangular feature is outlined by the red rectangle in the the photograph above.

Incidentally, astronomical alignments do not make themselves obvious at the circle but once seen, they are not forgotten. The mid-winter sunset is marked by two pointed stones (12 and 41, see plan above) aligned to the summit of Slieve Donard.

The circle stones reflect the shape of the mountain, which has two massive neolithic cairns on its summit.

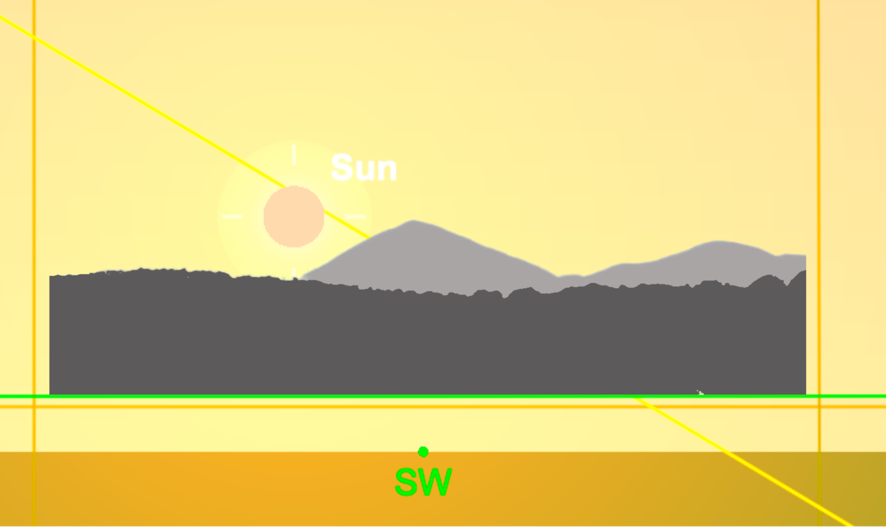

The elevation of the Slieve Donard summit from the circle is 2.7027°; below is a diagrammatic replication and estimate for the MWSS in 2300BCE as seen across the circle. The yellow line is the ecliptic – the sun tracks into the southern flanks of Slieve Donard as it moves towards a sunset azimuth of 228-229°. The established convention appears to have been to use the flank of a mountain, rather than its summit, as a calendrical marker.

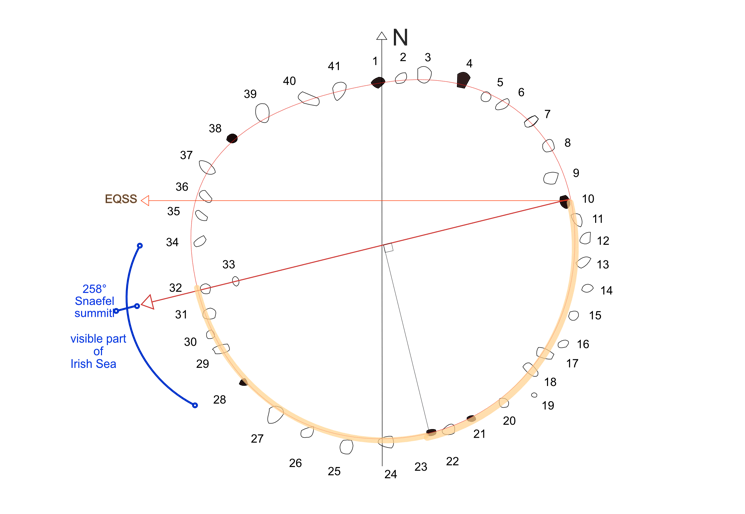

2. Equinox sunrise at Swinside

Swinside stone circle provides indubitable evidence for the recognition of the equinox sunrise. The so-called ‘entrance’ at its south-east is a striking and elegant placement of stones 18, 19, 20 and 21, arranged to delineate equinox sunrise. It closely resembles the quadrangular stone arrangement marking EQSS at Ballynoe.

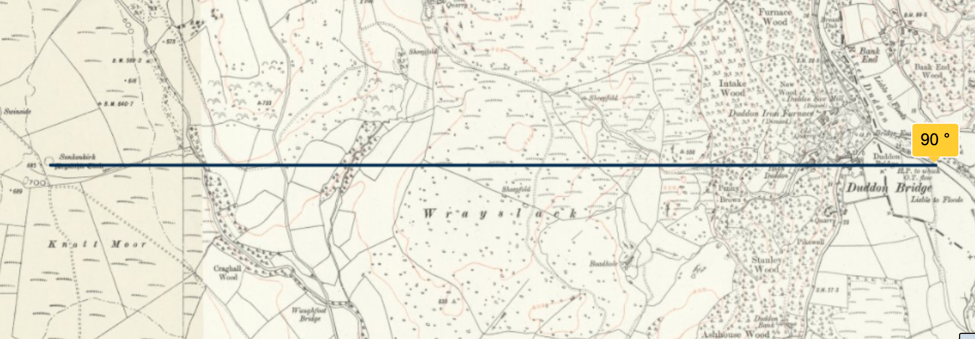

The position and plan of the circle was determined by the arrival of the equinox dawn light into the circle over the horizontal ridge of Wrayslack, one mile, 1.57k, to the east. This ridge shares the same elevation as the circle at 673 feet, 205m, , and thereby provides a flat horizon on which the equinox sunrise could be easily observed. It simultaneously provided a very precise bearing for the cardinal direction of East.

A few minutes after sunrise the full disk of the Sun reveals light travelling down stone 38; gradually a shaft of light appears on the ground near the stone and then develops across the circle to the ‘entrance’ stones. In the course of ten minutes, the shaft of light moves laterally across the base of the stone followed, for several minutes, by the shadow of stone 20. I regard this shadow as a confirmation for the day of equinox; on the days each side, the shadow would be below and to either side. The placement of the stones is therefore a considerable feat of engineering. On September 22nd 2025, the weather was kind enough to allow, possibly for the first time, a photographic record of this event on the day of the autumn equinox.

Swinside EQSR September 22nd 2025

Summary: Equinox at Ballynoe and Swinside

The architectural similarities between the two circles – especially the ‘entrances’ at each circle – reinforce the idea of a shared interest in the equinoxes. They are a detail in the wider reflected similarities of the circles, whose positioning on almost the same latitude indicates that a scheme was in place to reinforce their mutuality across the Irish Sea. A notion that calibrating the calendar between the communities cannot have served any purpose as knowledge of the equinox dates was already in place. The larger context of the Irish Sea and the Isle of Man need to be considered in answering this question. Our neolithic ancestors navigated a world of near and distant horizons without the aid of maps as used here to illustrate their achievements.

Living in the proximity of a stone circle in the modern era is possibly as close as anyone can now be to the experience of understanding and witnessing the annual passage of the year. For example, Margaret R. Curtis and her husband Ron have contributed significantly to understanding Callanais by their presence (Curtis & Curtis 2008). Similarly Martin Brennan and Jack Roberts carried out research into the stone art at Newgrange, the Boyne Valley and Loughcrew beginning in 1979 and ending a year later (Brennan 1983). Brennan demonstrates the sunlit illumination of rock art, at specific times in the annual calendar, in the neolithic passage tombs of those areas.

Predominantly, this interaction is between stone and the near-horizontal light of sunrises and sunsets.

Burnmoor and Elvaplain stone circles

Two other Cumbrian circles need to be considered in relation to Swinside. Both have a sightline to the Irish Sea and specifically to the Isle of Man. There is no archaeological information on the dating of any of the Cumbrian circles, so that the order of their construction is unknown. Both are situated to make use of observation points on hillsides directly to their west, thus marking locally the Equinox sunset viewed from each circle whilst also providing an elevated viewpoint extending across the Irish Sea. We shall also see below that these two smaller Cumbrian circles have a direct connection to Swinside.

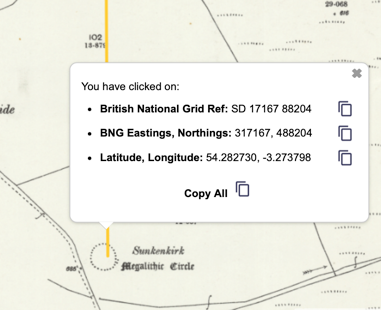

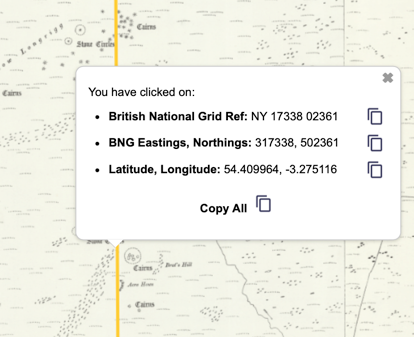

Burnmoor, or Brat’s Hill Stone circle

The circle is situated 0.7 miles (1.2k) north of the village of Boot in upper Eskdale, sited on moorland at an elevation of 862.9 feet, 263m. Its co-ordinates are 54° 24’ 36”N, 3° 16’ 29”W. The site is complex. The main circle has, according to a 1880 survey, a diameter of about 103 feet (31.39m) and 43 stones. Its diameter is the same as that of Elvaplain. Four other stone circles are nearby, as is a large cairn field of more than 403 cairns.1

The horizon around Burnmoor circle shows a marked contrast between east and west. To the east of are some of the highest and most dramatic peaks in Cumbria, which fall away southwards towards Hard Knott Pass. By contrast, to the south and west of the circle the horizon is close by, consisting of rolling post-glacial moorland.

Significantly, WSW of the circle the elevation drops to reveal a short stretch of the Irish Sea – a window that played a significant part in the positioning of the circle.

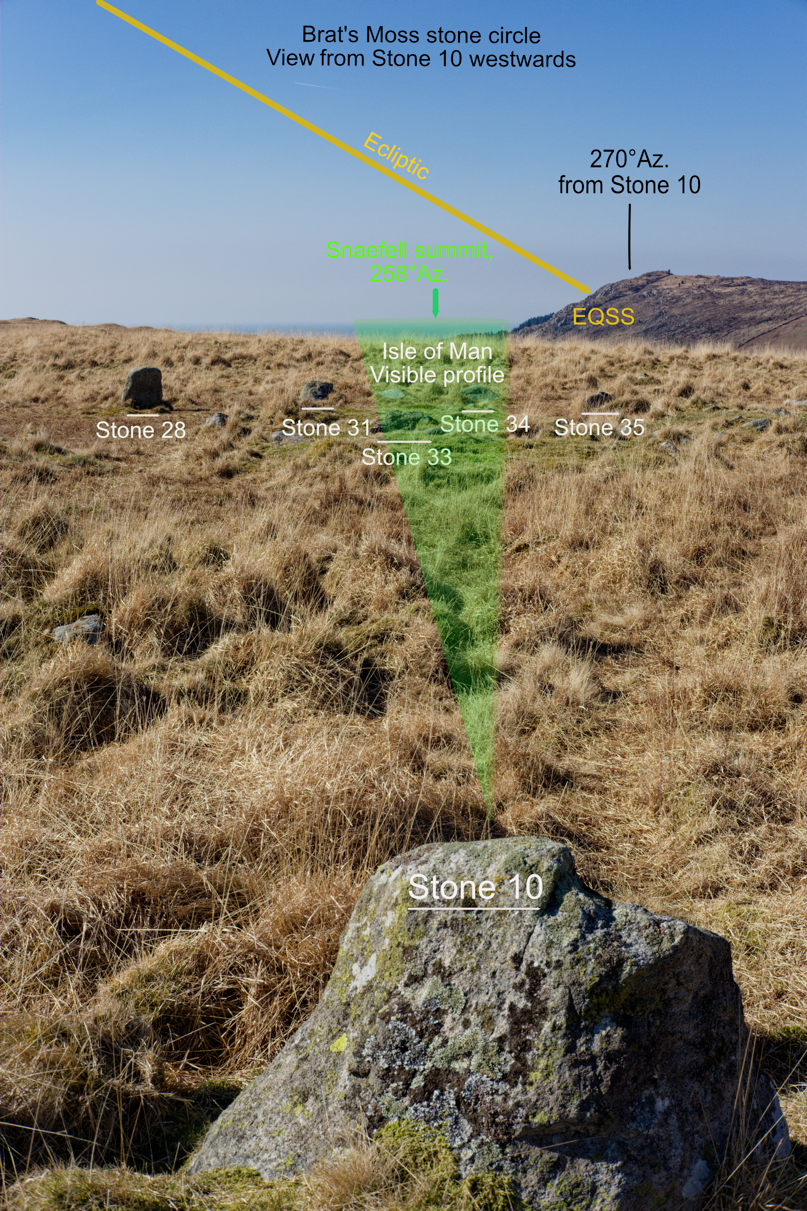

Burnmoor circle is, to use Thom’s term, a ‘flattened circle’, part constructed on a half-circle with its opposite section on a flattened curve (see diagram). The half-circle would have been outlined on the ground by scribing a straight line as a basis for the circle’s diameter. Then, at the central point of the line a peg and rope would have been used to scribe the line of the half-circle on the ground. The direction of the diameter line points to none of the cardinal directions. Instead, it is directed towards the Isle of Man and specifically to Snaefell (or possibly to the col) on the distant horizon, at a bearing of 258°. In the circle, the line of the diameter is defined by a three-stone alignment between Stones 10, 32 and 33. On the west side of the circle, stones 28 and 34 appear to define the extent of the visible area towards the Irish Sea.

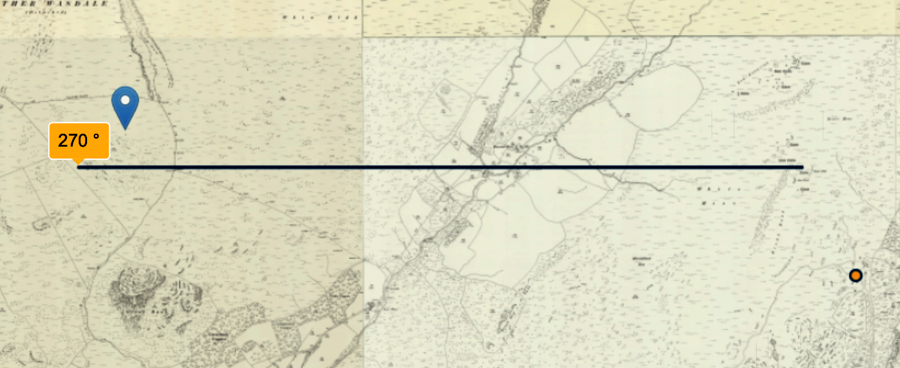

Equinox sunset at Burnmoor

The second tallest stone in the circle, Stone 10, additionally contributes to an Equinox alignment. Looking due west (270°) from the stone, the bearing crosses the flank of Irton Fell. The elevation of this point is 360 metres , which is 100 metres above that of Burnmoor circle. Allowing for the hill’s elevation, a viewer at the circle will see the equinox full orb sunset enter the slope at an azimuth of 268-269°

An observer standing on the hill summit would have an unrestricted view due west to the equinox sunset over the Point of Ayre at the northern tip of the Isle of Man.

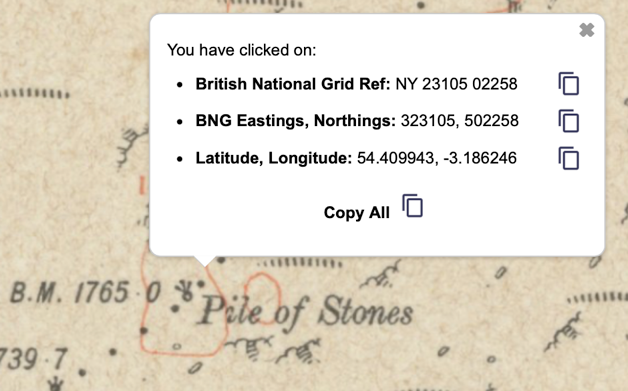

There is a possible backsight on this alignment. Marked on the early 25-inch OS maps east of Burnmoor circle on the ridge near Hard Knott, is a ‘pile of stones’, whose latitude corresponds exactly to that of stone 10. The possibility is that the stones are the remains of a neolithic cairn. Stone 10 is perhaps the tallest in the circle and appears to be in its original position at 54° 24’ 36”N, 54°.409N. The bench mark on the ‘pile of stones’ is also 54° 24’ 36”N, 54.409°N. The stone pile is 902 feet (275m) above the circle. There is then a clear sightline along a bearing of exactly 270°, between the stone pile and the Isle of Man. Viewed from the pile of stones, the three points on this bearing -–the stone circle, the hill and the Point of Ayre – would be visible and aligned on the equinox sunset.

Summary: Burnmoor stone circle

Despite the circle’s poor condition, it’s possible to recognise the significance of its positioning by means of its visual access to the Irish Sea and to the Isle of Man. Snaefell was a key component in the initial laying-out of the circle. Following the pattern of observation points at Carney Hill and Whitecombe Moss, Irton Fell doubles as the EQSS marker for the circle and the observation point for the Equinox sunset behind the Point of Ayre.

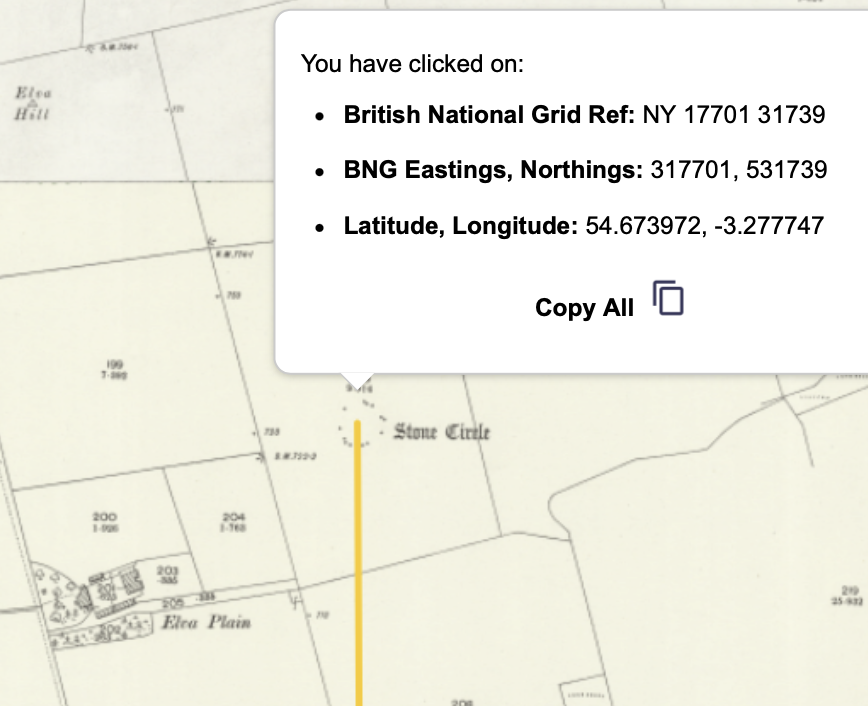

Elvaplain stone circle

The circle stands on terrace that slopes slightly downhill to the south. Originally it had 30 granite stones, of which 15 remain. Historic England describes Elvaplain as an almost perfect circle with a diameter of 30.5 metres, which bears comparison with Burnmoor at 31.4m, and Ballynoe, where the diameter is 33.5. metres, as reported by Burl.

The circle is in poor condition. According to Historic England (2026):

‘those in the north east quadrant are level with the ground, one on the east side has recently become partly buried, and the remainder of the stones have fallen, with the possible exception of the stone due west of centre which stands to a height of 0.7m”.1

It appears that the site was much damaged at the time of early modern agricultural development:

In John Askew’s Guide to Cockermouth of 1872 he notes that some forty years earlier a Fletcher Grave of Cockermouth described two concentric circles on this site, the inner twenty paces and the outer sixty of which most were removed when the land was enclosed (https://www.themodernantiquarian.com/site/1708/elva_plain.html).

This is a great pity, since the circle’s position and elevation provide potential for near and distant astronomical alignments on the surrounding horizon lines.

EQSR at Elvaplain

There is a possible calendrical indicator directly east of Elvaplain, where the northern flank of Skiddaw provides a notch in which the equinox sun rises.

The circle is situated at 720 feet, 220m, with a broad 360° horizon around it – close to the north and more distant to the south and south-west. Its coordinates are 54° 40’ 26”N, 3° 16’ 40”W. On its slope, there appear to be several possibilities for monitoring of the Sun. Among them are equinox sunrise over Skiddaw (photo above). In the opposite direction, there is a low summit at 833 feet, 254m. on Setmurthy Common. It is precisely at 270° west of the circle – the direction of equinox sunset – and has an uninterrupted view of the Irish Sea. Known locally as Watch Hill:

it is an excellent viewpoint. Skiddaw, Blencathra, the Lord’s Seat group and Grisedale Pike are all seen, and there is a first-class view of the Cockermouth area and the Solway Coast AONB. (Wikipedia, 2025).

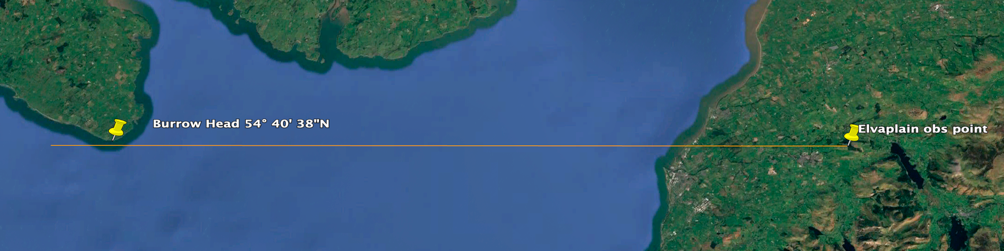

A pattern is followed, previously seen in the vicinities of Ballynoe, Swinside and Burnmoor, where a high point to the east or west of the respective circle provides a panoramic view of the Irish Sea. From this hill the Equinox sunset would occur directly behind Burrow Head in Dumfries and Galloway at latitude 54° 40’ 42”N, 4° 23’ 43”W.

The Isle of Man is visible from Elvaplain circle, although diminished in profile by the Earth’s curvature. Viewed from the circle, the lower 102 metres of the island are hidden below the horizon. Taking this into account, Snaefell’s summit therefore projects 1700 feet, 518.5 metres, above the horizon with a summit elevation of 0° 19’ 48”. Snaefell is at an Azimuth of 239° 20’, viewed from the circle. A sunset viewed behind Snaefell at the azimuth of 239° 20’ would have occurred in early February and November. Using the SkySafari reconstruction for 2300 BCE (see fig) the sun possibly touches Snaefell summit and then tracks north to set behind the hills in the area of Slieau Monagh,

This sunset bearing is calendrical, as it indicates the cross-quarter days in early February and November – in the Celtic calendar, Imbolc and Samhain. The cross-quarter days occur mid-way between the equinoxes and solstices.

Summary: Elvaplain

It’s not possible in this article to demonstrate the full range of possible astronomical horizon events at the site. Without doubt, its position was selected because of its potential for a conjunction of those alignments. The equinoctial sunrises and sunsets are recognised, particularly the sunset over the hill on Setworthy Common, from whose summit a considerable expanse of the Irish Sea is visible, including the Isle of Man and Burrow Head, behind which the equinox sunset occurs. The positioning of the circle in relation to the hill follows the pattern and function established at the three sites already examined. However, there is yet one other factor that connects the three Cumbrian sites that will be examined below.

The four circles: a summary

The stone circles of Ballynoe, Swinside, Burnmoor and Elvaplain share distinct characteristics despite their separation across the Irish Sea and, in the case of the three Cumbrian circles, a 27 miles, 43.5k, separation north to south. All have clearly indicated references in stone to either the Equinox sunrises and sunsets with the exception of Elvaplain, because of its poor condition. All have nearby high grounds that serve as both local and distant reference points for indicating the days of the equinox. Whilst Ballynoe and Swinside have no sight of the Isle of Man, the island is clearly indicated in the means by which they were positioned at the cardinal points of east and west. The two northern Cumbrian circles appear to be positioned because of their respective calendrical sightlines to the island.

It is unfortunate that there has been no sustained archaeological investigations at the circles, so that we have no idea of their datings or chronology. All four circles are the largest on the borders of the Irish Sea. Their distance from the sea is considerable yet their associated sea horizons are evidently significant and meaningful. Holistically we are made aware of a long-term project involving several communities having extensive communication and planning at distance. There are other stone circles nearer to the Cumbrian coast, but none show the characteristic environments of the four here selected. Additionally, the stone circles at Greycroft and Blakely Rise are thought to be reconstructed. To an experienced eye, the modern reconstruction of the stones in the northern circle at Burnmoor has no meaningful relationship to the immediate environment. The four circles examined here are therefore not arbitrarily selected.

The Isle of Man and the Irish Sea

The Isle of Man was evidently a focal point for the four stone circles. On the island, there is a multiplicity of prehistoric sites, among them megalithic sites dating from the early neolithic. In all probability the island had profound symbolic, cultural and geographic significance for the cultures on each side of the Irish Sea. A part of that significance can be recognised through the use of the Equinoxes to establish cardinal directions and linkage between the circles on adjacent shores.

One site in particular site may have been the origin of the network. Cashtal Yn Ard is a chambered tomb located on a hill 492 feet, 150 metres, near the east coast of the Isle of Man. It dates from approximately 3500 BCE, in a group of five megalithic tombs between Clay Head and Maughold Head. The structure is aligned on a bearing slightly north of west at 277°; the west end is a paved forecourt edged by standing stones behind which a single row of five cists or chambers containing burials runs eastwards from a small entrance between two of the forecourt stones. Developed in a number of stages, a mound of earth and stone was used to cover the burial chambers. Together with the forecourt, the total length of mound is 128 feet, 39m. Its eastern end overlooks the coastline. At this end there is a ‘burnt mound’ presently 0.9 metres high consisting of slabs laid on top of each other to create a platform containing burnt shale. In the 1932 excavation there was no evidence of bone. The mound remains un-excavated (Henshall 2017). The evidence of fire at this location may possibly indicate that it served as a navigation beacon.

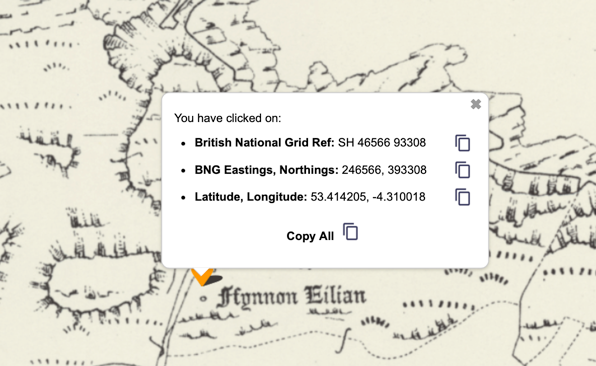

The site’s location is significant, being due west of Swinside’s proposed observation point at Whitcombe Moss, visible over 40 miles away. The two locations share the same latitude: the trig point on Whitcombe Moss is 54° 16’ 30”N, Cashtal Yn Ard is 54° 16’ 31”N. They are apart latitudinally by just 100 feet, 30 metres.

Viewed from Cashtal yn Ard the Cumbrian skyline shows Whitcombe Moss to be a low dip in the surrounding Cumbrian fells. It is the position of the equinox sunrise in 3200 BCE2 as viewed from Cashtal yn Ard.

The illustration shows the position of the sun a few minutes after the equinox sunrise. The sun shows first glimmer in the col of Whitcombe Moss then tracks along the northern flank of White Combe.

Cashtal yn Ard dates from a millennium prior to the construction of the stone circles. Whitcombe Moss may have therefore gained recognition in the early neolithic as a significant location. Their are neolithic cairnfields nearby at Little Grissoms , 54° 17’ 12”N, 3° 19” 24”W. Later, when the stone circles were constructed, its significance played a key part in aligning the Ballynoe and Swinside stone circles. Below, the latitudes of the observation points in this history show very close correspondence.

| Location | Latitude | Longitude |

| Carney Hill | 54° 17’ 24”N | 5° 42’ 40” W |

| Coll, Isle of Man | 54° 16’ 39”N | 4° 25’ 50”W |

| Whitecombe Moss | 54° 16’ 30”N | 3° 18’ 16”W |

| Cashtal yn Ard | 54° 16’ 31”N | 4° 21’ 51” W |

The Irish Sea coastlines and its megalithic sites

Working their way along the western seaways, travellers would thus have been following a well-known and long-established routeway. The pattern of tidal streams and flows enabled movement along a north/south axis, with only a minimal period of exposure to wind and waves blowing in from the Atlantic Ocean. (Callaghan & Scarre 2009)

It is now generally accepted that the western seaways of Britain and Ireland were navigated in journeys originating in European Atlantic communities. Sea-going boats have been found in the Mediterranean dating from 5000 BCE (Gibaja et al, 2024) although the physical evidence for boats in British waters is sparse prior to 2000 BCE. The possibilities are that so-called “colonising” travellers met with local settled communities, evidenced in the mixing of distinct pottery styles. It is unclear if sea-going vessels used sail or paddle, or a mixture of both. What does seem certain is that, away from the Atlantic, the winds and currents in the Irish Sea encouraged sea travel. The Isle of Man must have played a significant role in these travel routes, because it has a number of curious correspondences with the surrounding coastlines of Scotland, Cumbria, Wales and Ireland.

A scheme for navigating the Irish Sea appears to have been established using the extreme easterly and westerly points of the island and, from those points, taking bearings northwards or southwards.

How this was achieved is unknown, since there was no Pole Star in the neolithic period. Evidence, in the form of prominent megalithic structures or associated sites, at each end of these bearings indicates that the scheme was established in the early neolithic period, or earlier.

For clarity, the geography of the Isle of Man and the surrounding mainland coasts is presented below in the form of maps (i.e. the Archimedean viewpoint). But the key features need to be seen from a different viewpoint – that of the navigator in a world of horizon and this approach will lead to the practicalities and motivations for travel in the Irish Sea.

Navigating horizons

North: Maughold Head to Cairnholy Cairns

Maughold Head defines the easternmost extreme of the Isle of Man. Travelling by boat or canoe northwards, the sailor arrives on the shores of Wigtown Bay, where Kirkdale Burn enters the sea.

Two-thirds of a mile, one kilometre, north of the landing point are the neolithic chambered cairns of Cairnholy 1 and 2. The cairns’ estimated dates of construction are the fourth millennium BC. At an elevation of 400ft, 120metres, they hold an unobstructed view to the Isle of Man, framed by the Kirkburn Valley.

| Location | Longitude | Construction date |

| Maughold Head | 4° 18’ 33”W | Neolithic copper deposits |

| Cairnholy Cairns | 4° 18’ 39”W. | ? 3500-3000 BCE |

South: Maughold Head to Ffynnon Eilian

From Maughold Head travelling due south, the northern shore of Anglesey is reached 300 feet,100 metres, east of a small fresh water outlet. The water flows from Ffynnion Eilian, a spring or well with long-standing associations with healing. (Both the north and south ends of the bearing lead to fresh water, an essential supply for sea travel). However, there is a further significance to this location. Less than 2.5 miles, four kilometres, to the south west is Parys Mountain, the site of massive copper deposits.

There is evidence that copper mining began here in the early neolithic:

During later centuries when underground mining commenced some of these ” ancient Druidical workings” collapsed. A number of these have been found underground at Parys mine. The collapses contain of a mixture of hammer stones and oak charcoal. Three samples of charcoal have been radio carbon dated by the British Museum and have returned dates of 3500 to 3600 BCE (Grwp Tanddaearol PARYS 2025).

North: The Calf of Man to the Mains of Park

The Calf of Man is a small island at the southerly and westerly extremes of the Isle of Man. It has a summit at 417 feet, 127m . A bearing extended northwards reaches the coast of Dumfries and Galloway at the estuary of the Water of Luce, a considerable river. Specifically, the bearing meets the present day Mains of Park, 100 feet, 30m .

| Location | Longitude | Construction date |

| Calf of Man | 4° 49’ 29”W | Neolithic: copper deposits |

| Mains of Park | 4° 49’ 29”W | Part of massive settlement

3500 BCE to medieval |

The locations are 56.6 miles, 91k, apart.

Recent excavations in the Mains of Park reveal extensive flint production and food processing of hazelnuts. Carbon dating shows the site was used from the mesolithic to the neolithic.This area is the eastern end of a six-kilometre excavation stretching from its western end near Dunragit. It contains the earliest Mesolithic house in south-west Scotland; a Neolithic timber alignment linked to the ceremonial complex; two Bronze Age cemeteries; and an Iron Age village. It was in use for eight millennia (Bailie 2020).

South: Calf of Man to Carreg Coetan Arthur

A bearing due south from the Calf of Man passes within 1.5 miles, 2.4k, of Bardsey Island, of the western tip of the Lleyn Peninsula. The island has a summit of over 500 feet, 167m . at Mynydd Enlli. The bearing proceeds southwards to meet the Welsh coast two miles above the Avon Nevern estuary at Newport. In Newport is Carreg Coetan Arthur, a dolmen that was possibly sited on a neolithic shore. Bone fragments have been carbon dated to 3500 BCE. Its longitude is 4° 49’ 42”W. The area was possibly used for the transfer of bluestone and dolerite axes from the Preseli Mountains, 5 miles, 8k, to the south-west, Dolerite axes from these hills have been found in Ulster.

| Location | Longitude | Construction date |

| Calf of Man | 4° 49’ 29”W | Neolithic: copper deposits |

| Carreg Coetan Arthur | 4° 49’ 42”W | Carbon dating 3500 BCE |

Summary

Each bearing leads to:

- Fresh water

- An associated megalithic site dating from the early neolithic or

- Copper deposits and workings dating from the early neolithic.

- Stone artefacts

The navigation scheme was possibly in operation from the early neolithic or the mesolithic. The locations of megalithic structures must have had associated communities; commodities such as copper, stone axes, pottery, animals, grain etc are trading from these to the far reaches of the Irish Sea and possibly with those on the near continent. The bearings are the possible traces of a rule-of-thumb navigation scheme or system for the Irish Sea.

Navigation points

North / south navigation points

An operational navigation scheme would have been aided by prominent features on the surrounding coastlines. For example, travelling south from Dunragit, the Isle of Man is clearly visible. The Calf of Man would be visible as the west coast of the island was navigated. Steering west of Anglesey, the Lleyn Peninsula leads to Bardsey Island. The journey to Carreg Coetan Arthur could possibly rely on the Welsh mountains to the east until Strumble Head would give a clear indication of the approaching eastward turn to the Avon Nevern estuary. Travelling northwards from Ffynnon Eilian was a shorter journey, with the east coast of the Isle of Man to keep to until Maughold Head indicated that the coastline towards the Point of Ayre should be kept parallel. The Kirkburn Valley framed the elevation of Cairnholy:

Cairnholy… was built on top of a domed rock outcrop. At all of these sites, it would seem that the builders of each monument could have made the construction process considerably easier by avoiding outcrops and natural features. Instead they seem to have deliberately chosen distinctive outcrops on which to construct sites which adds weight to the suggestion that the precise location of each site was much more important than mere “convenience’ or practicality. (Cummings 2009)

East / west navigation points

In terms of navigation these are connected to shorter routes around the Isle of Man. Visibility, whilst still a key factor, would not pose the challenges of north and south navigation. Nevertheless, there are similar possible geographic correspondences between the Isle of Man and its surrounding coastlines. On almost the same latitude as the Calf of Man, westward is Carlingford Loch whose area is rich in Megalithic sites, including the portal tomb of Kilfeaghan Dolmen, Clermont Carn on top of Black Mountain, 1670ft, 510m., dating from the early Neolithic. East of the Calf of Man is Walney Island, where there is evidence of Neolithic settlements, farming, flint working and polishing of Langdale axes. Similarly, to the East of the Point of Ayre, on the Cumbrian coast at Ehenside Tarn was a neolithic settlement where Langdale axes were polished and possibly furnished with wooden hafts. There is also the possibility of a dugout canoe with paddle (Heritage Gateway 2012).

Burnt mounds

Burnt mounds are the most common type of prehistoric remains found around the coasts of the Irish Sea. They consist of piled stones and charcoal. Their function is unknown, perhaps serving a multiple of purposes. Often associated with water, their cited uses suggest cooking, brewing, textile and leather manufacture.

Around the Irish Sea, their proximity to coastal routes suggests they served as seasonal camping areas or temporary stopping points for groups traveling between Ireland, southwest Scotland, western England, and the Isle of Man.

At Dunragit the mounds sit close to the shoreline:

the burnt mounds were set on the grey clay of the former estuary at Whitecrook Bay. In the east the burnt mounds at Boreland Cottage Upper were set on a sandy clay within another smaller bay defined to the north by the curving southern edge of a raised beach, on which the funerary complex of Boreland Cottage Lower was located to the north, and on which the Neolithic settlement activity of Mains of Park was located to the east (Baillie 2020).

However, evidence of mounds and fire appears at elevated areas, for example:

…at Cairnholy I in south-west Scotland a whole series of charcoal spreads were uncovered in the forecourt area, probably indicative of small fires (Piggott and Powell 1949).

As we have seen, this is somewhat replicated at Cashtal Yn Ard, where the burnt mound at its eastern end faces the sea. It is entirely possible that fires at the mounds acted as navigational aids for seafarers in darkness or low visibility.

Irish Sea travel in the neolithic

At present, very little is known about neolithic sea travel. In 2010, one man and his dog crossed the Irish Sea in a kayak, from St. Bees to Ramsey, in nine hours. (BBC News 2010). More recent records show reverse traverses in sea kayaks, west to east, timed between six and ten hours, (Performance Sea Kayak (2026). But there can be little comparison between custom-designed sea-going kayaks and neolithic wooden vessels that may have been powered by paddle or sail. Perhaps the timings of the kayak journeys between the Isle of Man and the Cumbrian coast give, for the equivalent neolithic journey, a working approximation of one day’s travel in daylight. This same figure could be applied to distances between the Isle of Man and the Galloway coastline to the north. Wind and tides would of course play a significant part.

We can then estimate that, for example, a journey from the Isle of Man southwards to Anglesey may have taken two days, perhaps with a night at sea. A similar journey southwards to Carreg Coetan Arthur may have taken four to five days, depending on conditions. Landfall stops for water and food may have been necessary – Holyhead and Bardsey Island provide potential provision and shelter a day’s journey apart.

Garrow and Sturt (2011) used a computer simulation to evaluate conditions in the western seaways around Britain using tidal and wind data from the United States Navy Marine Climatic Atlas (US Navy 1995). Access to the western seaways of the British Isles was heavily dependent on the seasons. Accordingly, boats (paddle or sail) leaving the near continent would not have been able to cross the English Channel in winter. The data for paddled boats in the Irish Sea is reported as follows:

Between Antrim and Argyll strong following winds in winter would make travelling to Argyll easy but return voyages more difficult. Spring would have good conditions for sailing in both directions. In summer, winds are lighter than in spring but two-way travel is not difficult. In autumn, travel from Antrim is easiest and if voyagers wait for favourable winds the reverse journey is easy. The same pattern would apply to contacts between the Boyne Valley and Anglesey. Except in winter, winds in this region are quite variable and given the short sailing time of one to two days would only require waiting for favourable winds. (Garrow & Sturt 2011)

In other words, travel in winter would have been reduced considerably and may have been avoided completely. Garrow and Sturt divide the year into the standard four seasons. But transition periods between the seasons are a factor – when was it deemed safe to travel in the Irish Sea?

The emphasis placed on the Equinoxes in the four circles may have provided the answer. Certainly the period between the Equinoxes must have been full of productive activity – farming, trade and associated travel included. But the months between high summer and the depths of winter needed to be reckoned with. The forty days before the March Equinox is a transition period, as is the same number of days after the September Equinox. The forty days periods coincide with the cross-quarter days in early February and early November. We have seen the emphasis placed on the identification of the Equinoxes in all four circles. The February and November cross-quarter days are indicated in the Azimuth between Elvaplain stone circle and the Isle of Man. Perhaps this is an indicator that the navigation and calendrical systems worked in tandem.

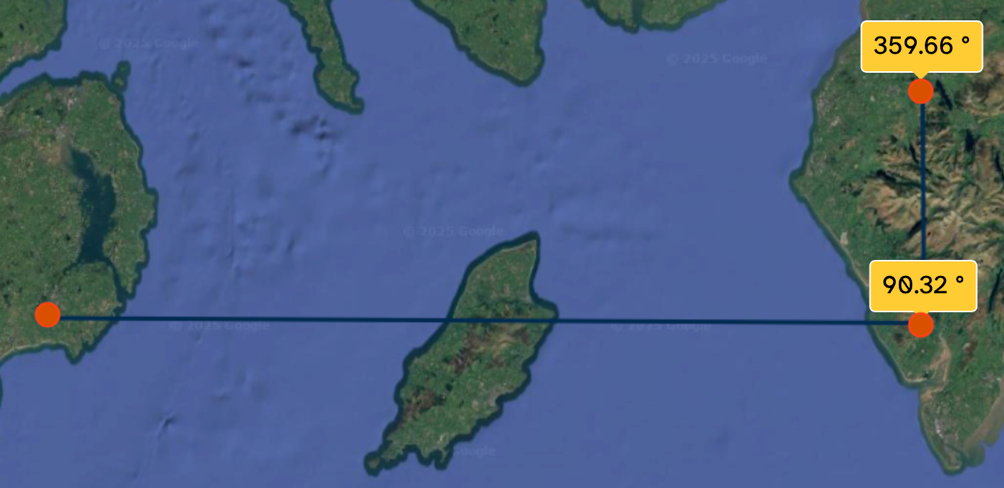

The three Cumbrian stone circles

If the ability to determine the bearings of True North and South was developed in the Irish Sea during the mesolithic or late neolithic period, that knowledge was later applied on land to the three neolithic Cumbrian circles examined here. Between Swinside and Elaplain, the most northerly, is a distance of 27.03 miles, 43.51k. Using online 25-inch OS maps to measure centre-to centre between these two circles, the bearing is 359.66°, one-third of a degree from True North. En route it passes 35 feet to the west of Burnmoor circle, through a possible stone mound or cursus.

There I can be no doubt that this alignment of the three circles over some of the highest peaks and deepest valleys of Cumbria is physically and astonishingly difficult to achieve. Sighting by the present North Star, Polaris, was not possible in the neolithic era; there was no clearly identifiable star at the celestial pole.

How was it so accurately aligned on True North to within 0.33° and why? There is no easy answer.

Added to it, is of course the equally difficult question of the alignment between Ballynoe and Swinside, at that location forming an almost exact 90° angle with the Cumbrian circle alignment.

At this time, there is no immediate answer.

Postscript

I am neither an archaeologist nor an astronomer. The above insights originate in site visits, sometimes several to the same site over years in order to evaluate and re-evaluate the research. My training, education and practices are in the visual arts. Observing the relationships between megalithic structures and their horizons developed from those practices. Taught to draw accurately at art college, the emphasis was on measuring the environment around the figure, or object. This helps tremendously to establish proportion by relationships. By analogy, being in the landscape requires an awareness of the cultural importance of the four directions within monumental design and the way that light defines those directions and their divisions.

As archaeology delves deeper into detail made available by the microscope, the phenomenology of landscapes and skycapes is, by contrast, a complementary and corrective study. Sunlight and moonlight were important factors in neolithic monumental design.

I welcome constructive comments and insights, especially from those who have carried out site visits.

Acknowledgement

In Stone Circle Calendars, A New Understanding, Jack R Morris-Eyton examines with scrupulous care the role of shadows and light at Swinside. Light-lines enter the circle and create a continually changing display of light and shadow, which cross the whole of the circle’s interior, at times to stones opposite, indicating key times of the year. Our equivalents are the hands on a clock; but the circles describe time in a wholly circular manner. His research extends to the Swinside locality and beyond. His work brought my attention to the north / south alignment between the three Cumbrian stone circles. (O’Neil S. 2023)

© 2026 I A Ingram

All diagrams, illustrations and photographs by the author unless otherwise stated.

Reference list

- Bailie, W. (2020) Dunragit, The Prehistoric Heart of Galloway.

- Glasgow: GUARD Archaeology Ltd. Available from: https://www.guard-archaeology.co.uk/DunragitBlog/DunragitPopularPublication.pdf. [Accessed 23 January 2026].

- BBC News (2010) One man and his dog kayak from Cumbria to Isle of Man. Available from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-isle-of-man-10987377. [Accessed 23 January 2026].

- Brennan, M. (1983) The Stars and the Stones : Ancient Art and Astronomy in Ireland. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Burl, Aubrey (2005) A Guide to the Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Burl, Aubrey. (1976) The Stone Circles of the British Isles. New Haven ; Yale University Press, Print. p.238.

- Callaghan, R. & C. Scarre (2009) Simulating the Western Seaways. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 28: 357–72.

- Cummings, V. (2009) A View from the West : The Neolithic of the Irish Sea Zone. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Curtis, G. Ronald, and Margaret Curtis (2008) Callanish : Stones, Moon & Sacred Landscape : 2008 Windfarm Submission. Callanish, Isle of Lewis: R. & M. Curtis.

- Department for Communities, Northern Ireland Sites and Monuments Record (2025) Available from: https://apps.communities-ni.gov.uk/NISMR-PUBLIC/Details.aspx?MonID=8031 [Accessed 23 January 2026].

- Garrow,D. Sturt, F. (2011) Grey waters bright with Neolithicargonauts? Maritime connections and the Mesolithic–Neolithic transition within the ‘western seaways’ of Britain, c. 5000–3500 BC.ANTIQUITY 85.

- Gibaja, Juan & Mineo, Mario & Santos, F.J. & Morell Rovira, Berta & Caruso Ferme, Laura & Remolins, Gerard & Masclans, Alba & Mazzucco, Niccolò. (2024) The first Neolithic boats in the Mediterranean: The settlement of La Marmotta (Anguillara Sabazia, Lazio, Italy). PLOS ONE. 19. 10.1371/journal.pone.0299765.

- Grwp Tanddaearol PARYS (2025) Bronze Age Copper Mine Anglesey. Available from: https://parysmountain.co.uk/bronze-age/ [Accessed 23 January 2026].

- Lynch F. & Davey P. Eds. (2017) The Chambered Tombs of the Isle of Man : A Study by Audrey Henshall 1969-1978. Summertown, Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd.

- Heritage Gateway (2012) Historic England Research Records. Ehenside Tarn. Available from: https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/Results_Single.aspx?uid=8682&resourceID=19191. [Accessed 23 January 2026].

- Historic England (2026) Large regular stone circle 240m ENE of Elva Plain. Available from: https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1013385?section=official-list-entry [Accessed 23 January 2026].

- O’Neil S. (2023) ed. Stone Circle Calendars: A New Understanding. Nortoft Publishers

- Performance Sea Kayak (2026) Crossing Isle of Man – England. Available from: https://performanceseakayak.co.uk/Pages/Crossings2a/crossingsIOMEngland2a.php#:~:text=Route Distance: ~27 nm / [Accessed 23 January 2026].

- The Modern Antiquarian (2026) Miscellaneous. Available from: https://www.themodernantiquarian.com/site/1708/elva-plain. [Accessed 23 January 2026].

- Wikipedia (2025) Sacred Mountains (last updated 30 December 2025). Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacred_mountains [accessed 24 January 2026].

- Wikipedia (2025) Watch Hill (Cockermouth). Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Watch_Hill_(Cockermouth). [Accessed January 23 2026].