Ronnie Gallagher and Tom McLellan offer evidence associating solar alignments with simulacric images, serpent worship, and indications of a significant prehistoric ritual landscape.

Introduction.

A work secondment in Azerbaijan alerted Ronnie to large-scale anthropomorphic and zoomorphic imagery at archaeological sites.1 Studies by Dr. Leonid Marsadolov in the Altai region of Siberia have indicated solar reverence, such as an equinox sunset alignment in the mouth of a ‘fish’ at Mt. Ocharovatelnaia.2 Among the Neolithic sites was possibly the world’s largest serpent carving, over 1000m long; its sunset orientation raised the question whether other serpent landforms might also have sunrise and sunset connections suggestive of solar religious significance.

This led to a visit to the Serpent Mound at Loch Nell,7 where it seemed that the mound may indeed have been created with solar observation in mind. Certainly, the eye is drawn to the E, along the body of the serpent to the distant Ben Cruachan and summer sunrises. However, like the Ohio Serpent Mound, which orients to the W and sunset, so too does the Loch Nell earthwork. However, apparent alignments to a cairn mound and three white granite marker stones suggested other possible solar sunset alignments.3

Loch Nell: Rubha na Moine Crannog and the Skull Stone

In 2008, we also visited other prehistoric monuments in the area, including a chambered cairn, Strontoiller stone circle, Strontoiller standing stone, burial cairns, various cup-marked boulders and (views of) two crannog islands.

Hiking over the Ballygowan estate to get a good view of the crannog Rubha na Moine (RnM), a curious skull-shaped granite boulder was found overlooking the crannog. The ‘Skull Stone’ appeared to be deliberately shaped, with its ‘face’ oriented towards RnM. While it may be a glacial erratic, its precarious positioning overlooking the crannog, and in alignment with the winter solstice sunrise (WSSr), seems potentially significant (Figs.1,2). 4

In 2018 the owner of the Ballygowan estate contacted Ronnie to inform him he planned to develop the land as a woodland for nature conservation, with over 190,000 trees5. He was keen to ensure that the Skull Stone would remain visible for visitors.

1 & 2. The Skull Stone, overlooking Rubha na Moine crannog (Ronnie Gallagher)

A visit to the Skull Stone with his forester Tom McLellan followed, and led to a commitment to try to photograph key sunrise and sunset events associated with RnM, the Skull Stone and Serpent Mound. This meant visiting the area in winter, summer and at Easter – and given Scottish weather, it remains a bit of a challenge! However, Google-Earth (GE) has proved valuable to test the alignments, as it can accurately determine sunrise and sunset positions and timings for any location.

In standardising alignments with GE, sunrise is considered the point at which the sun just appears over the horizon, and sunset the point at which the sun touches the horizon. Where the sun crosses the horizon is also important, and the spectacle generally lasts around 40 minutes, covering an azimuthal angle of around 15 degrees.

3. Crannog and Standing Stone alignment to the Winter Solstice Sunset (Tom McLellan)

Our first photo (December 2018) was taken from the hillside behind the standing stone looking towards the RnM crannog, down the length of Loch Nell and towards the winter solstice sunset (WSSs) (Fig.3). It confirmed the alignment between the crannog and the standing stone, and in time revealed that the configuration also included a submerged crannog at the SW end of the loch, re-discovered in summer 2019 – we call this ‘Blundell’s crannog’, after the man who had mentioned a second, lost, crannog. From this crannog, the view to RnM crannog should focus on the summer solstice sunrise (SSSr). and did (Fig.4). Three artificial structures along the solstitial line – two crannogs and a standing stone – seemed more than coincidence.

4. Alignment with submerged crannog towards RNM crannog and SSSr (Ronnie Gallagher)

Given the solar astronomic associations of other Neolithic sites such as Maes Howe, Newgrange and Stonehenge, it is not unlikely that such orientation would be familiar to the crannog folk, which begs questions over whether these monuments were planned to sit along the solstice line, and over the age of the Loch Nell crannogs. Although crannogs can range from the Neolithic through to the Iron Age, does the association with the Strontoiller standing stone and presumably the associated stone circle and burial mound imply a Neolithic origin here, or a multi-period recognition of this association?

Another question concerns the importance and function of the RnM crannog. At 138m from the shoreline, it is significantly further out than other Scottish crannogs, which are typically around 30m from shore. Building an artificial island is a major task, so there had to be a good reason for it. Another oddity is that it was built beyond the natural protection of the nearby Rubha na Moine (=promontory of the peat or moss) and SW prevailing winds. Do these counter-intuitive elements imply deliberate siting for viewing solstice alignments, and if so, might RnM have served a religious purpose?

Loch Nell naturally orients NE/SW, lending itself to potential solstitial alignments; perhaps this is why the loch was selected, and why the area has such rich archaeology.

As for the Skull Stone, which sits above RnM, it is evident from GE that when viewed from the crannog the sun would set behind the stone on the summer solstice sunset (SSSs). Accordingly, Tom visited the island by kayak on a blustery day on 21 June 2018 to take sunset pictures, and was able to get some that further confirmed the value of GE as an investigative tool. He felt he might be the first in a very long time to view and grasp the meaning of this particular sunset, and that it was not just the skull stone, but also the small hillock it sat on that was part of the overall experience. From the photographs, the hillock can certainly be seen like an animal’s body, with its stone head or skull both positioned and scaled appropriately (Fig.5). To our modern eyes this may seem to be a trick-of-the mind, an example of pareidolia, but given apparent simulacric inclinations in prehistory, it’s likely that they too saw a large beast. If so, it supports the suggestion that the skull stone was not simply an erratic but was arranged to represent a zoomorphic impression, similar to the Serpent Mound.

5. View of Skull Stone on skyline at summer solstice sunset. Skull appears to have a body!

(Tom McLellan)

Could this then mean that Loch Nell has two metaphoric beasts as guardians? Perhaps, like Azerbaijan’s anthropomorphic images, this indicates that the Neolithic Loch Nell folk were animistic in their outlook and may have venerated the sun.

To recap then: for solstice sunsets when looking out from the Rubha na Moine crannog to the Skull Stone and Blundell’s crannog, these accurately align to the SSSs and WSSs respectively. For sunrises, the Skull Stone aligns with the RnM crannog to the WSSr, while RnM crannog aligns with the Strontoiller standing stone for the SSSr. The submerged Grianan Mor crannog to the S may also have astronomical significance.

Loch Nell SW End.

In the context of solar alignments, the key features of interest here are the Serpent Mound, a chambered cairn known as the ‘Tomb of the Giants and of the Finn’, Blundell’s crannog, Dalineun crannog, a stone mound, and three large granite boulders opposite the Serpent’s head.

Woolf, McKim and Murray, and McLennan have followed the local folklore7 about serpents and the Serpent Mound through 19th-century Scottish antiquarianism, and quote the important researchers John S Phené, Robert Angus Smith, J.S. Blackie and Constance Gordon-Cumming.8

It is worth noting that Phené’s excavation work in 1871 and a later commentary by Mrs. Gordon-Cummings in 1883 described the mound as “wonderfully perfect in anatomical outline”, “that the whole length of the spine was carefully constructed with regularly and symmetrically-placed stones at such an angle as to throw off rain”. This feature, she believed, had been instrumental in preserving the structure from erosion. She could see that the ‘spine’ was a long narrow causeway “made of large stones, set like the vertebrae of some huge animal”. On the burial mound – which she calls the ‘head’ – she found a circle of stones “exactly corresponding with the solar circle as represented on the head of the mystic serpents of Egypt and Phoenicia, and in the great American Serpent Mound”. Both commentators had no doubt that the Serpent Mound was artificial.

Serpent Mound Alignments.

The following list details apparent solar alignments from the Serpent Mound, looking towards:

Cairn 60m to the E. Orientation 267o. Possibly to observe equinox sunset.

Three granite erratics. These large boulders sit opposite the Serpent’s head and may have been intentionally placed: 1.150m distant. Orientation 245o. Possibly to view Samhain sunset (Oct. 31), to mark the end of harvest season and beginning of winter. 2. 145m distant. Orientation 234o. Possibly to view Imbolc sunset, a traditional festival marking the beginning of spring. 3.140m distant. Orientation 224o. Possibly to view winter solstice sunset.

Ben Cruachan. Various observers have noted that Ben Cruachan can only be viewed from the Serpent Mound at the SW end of the loch, the first opportunity to get a full view of the mountain when travelling W-E. Using GE it was possible to determine when the sun could be seen to rise from behind this impressive mountain – approximately 15th April and 29th August (Fig.6). These dates do not correspond to the traditional start and end of either astronomical or meteorological summer, nor the modern calendar. However, perhaps the ancient folk of Loch Nell considered their mid-year or ‘summer’ months to lie between the sunrises behind Ben Cruachan of April and August. This could be significant, for traditionally summer begins on 1st May, only two weeks different, and harvest time ends at the end of August.

6. Sunrise view from Mound to Ben Cruachan, April 15 & Aug. 29

Tomb of the Giants and of the Finn. Just as RnM crannog aligns to the Grianan mor crannog as noted above, both the Serpent Mound and Finn’s Tomb are aligned N-S at 181o, which may or may not be coincidental. Either way, the alignment will inform observers of noon when looking S, and of polar N.

Blundell’s crannog. GPS. 56°23’4.55″N 5°25’57.28″W. When viewed from the Serpent Mound’s head, this orients towards the winter solstice sunrise (WSSr) (Fig.7). Curiously, Blundell’s submerged crannog also sits on a direct line between the Tomb of the Giants and of the Finn and the Dalineun crannog, which needs to be considered for any possible significance.

7. View from Serpent Mound towards submerged crannog, Dec. 21, WSSr

Other Alignments

- Dalineun Crannog aligns to the Serpent Mound and the SSSs, as the sun touches the horizon.

- Blundell’s crannog a) Aligns directly to the RnM crannog and the SSSr, as discussed above. B) Aligns with the Serpent Mound at the SSSs as the sun dips below the horizon. Between the two crannogs the full SSSs may be observed.

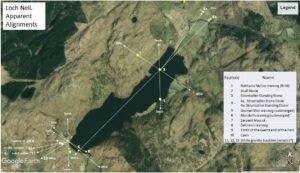

A summary of the various Loch Nell alignments is provided in Fig. 8.

8. Loch Nell features and their apparent solar alignments

From the various alignments associated with the Serpent Mound, it seems reasonable to infer that the head of the serpent was a focal point to observe solar sunsets and sunrises for key dates in the year. While other alignments might yet be discovered, there are sufficient to demonstrate that the mound, in addition to being a Neolithic cairn and ceremonial centre, may have functioned as a solar observatory. Taking other Loch Nell alignments into consideration, it would seem that the sun played an important role in the life of these ancient folk, who were presumably able to use it to judge seasons and determine important times for hunting, planting and harvesting, and possibly social occasions. Perhaps the sun featured prominently in their belief system.9

Making Sense of Loch Nell and its monuments

While the various alignments noted above seem evident, questions remain as to whether the Serpent Mound and Skull Stone Beast are natural or artificial, coincidental or designed. Answering these questions will require detailed archaeological, archaeo-astronomical and anthropological investigation.

Victorian antiquarians certainly considered that the mound was human-made, and that it may have involved serpent worship (ophiolatry).10 Indeed, ophiolatry may have been known in Scotland, as there are other serpent mounds at Skelmorlie on the Clyde and Glenelg on the mainland opposite Skye.

Also, in England, the Neolithic Rotherwas Ribbon (or Dinedor Serpent) near Hereford was discovered in 2008 during road construction; it comprised fire-cracked stones carefully laid to form a surface covering a distance of 300m (65m of this now buried under the new road), and dates back to 2150 BCE.11 As an important archaeological find, it offers an opportunity to study ancient serpent cults in Europe, but inexplicably was not listed as an ancient site.12

The low relief of the Rotherwas Ribbon indicates a different nature from the Scottish serpent mounds, but its form suggests that an archaeological investigation of the Loch Nell mound might well add to understanding of ancient culture and tradition. Limited excavation might confirm Phené’s findings and determine to what extent the mound is artificial. Interestingly, the Oban Times reported that Phené intended to make a detailed model of the mound and donate it to the town,5 but whether this was done is not known.

As for the three granite boulders opposite the serpent’s ‘head’, if these sit on bedrock or glacial till they may simply be natural erratics. However, if they have soil below them, this could indicate they were repositioned in the past. The Skull Stone beast is perhaps more difficult to investigate, but a petrologist might ascertain if it was carved.

Possibly the most intriguing observation is that all four crannogs are associated with solar observations, indicating they may have been deliberately positioned with potential solar alignments in mind. If this was the case, then it may be anticipated that other lochs with crannogs might show similar alignments. To test this, a brief study of the thirteen Loch Tay crannogs was carried out using Google Earth, noting alignments between crannogs, plus a single standing stone. Twelve alignments were found, with orientations towards summer solstice sunrise (2), summer solstice sunset (2), winter solstice sunrise (3), winter solstice sunset (1) and equinox sunrise (4). Fig.9 shows the relevant alignments, which obviously need to be further investigated – but 12 putative alignments suggest the possibility of intention. Should research find that crannog-to-crannog solar alignments, possibly involving standing stones, are not uncommon, this could shed further light into prehistoric culture and belief locally.

9. Location of crannogs in L. Tay and apparent solar alignments

References

- Gallagher, R. ‘Anthropomorphic Images in Azerbaijan’s Landscape and their possible significance’. https://www.academia.edu/37625563/Anthropomorphic_images_in_Azerbaijans_landscape_and_their_possible_significance

- Marsadolov, L., 2005. ‘Mt Ocharovatelnaia and Mt Siniaia in Altai: legends and reality’. Folklore 31: 57-78. http://www.folklore.ee/folklore/vol31/marsadolov.pdf.

- Kurgan, 2008. ‘Serpent Mound, Loch Nell’. https://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=19474.

- ‘Loch Nell Skull Stone’. https://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=19473.

- Woodland Plantation’. https://www.obantimes.co.uk/2018/03/08/community-pride-to-love-and-nurture-new-oban-woodland/.

- Lockyer, N. The Dawn of Astronomy. 1894. p.145.

- Woolf, Jo. ‘Loch Nell: The Tomb of the Giants and a Serpent Mound’, https://www.thehazeltree.co.uk/2019/07/26/loch-nell-the-tomb-of-the-giants-and-a-serpent-mound/, July 26 2019; Susan McKim and Edward Murray. ‘The Serpent Shall Rise from the Mound’, Northern Earth 152, 2018, pp.16-21; McLellan, Gordon and Tom. The Serpent Reprised, Northern Earth 153, 2018, pp.28-29.

- C.F. Gordon Cumming, ‘The Serpent-Shaped Mound of Loch Nell’, in Good Words, Strahan & Co., London 1872.

- Constance F Gordon-Cumming, 1883. ‘In the Hebrides’, Solar Deity, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solar_deity.

- ‘Snake worship’. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Snake_worship

- ‘Rotherwas Serpent’. https://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=17076.

- English Heritage appear unwilling to accept a non-natural explanation – a gravel hollow underlay the ‘Ribbon’ – and the apparent subsequent development of it as a ‘feature’ in the Bronze Age, despite the submissions of the academic excavators of relevant dating samples to c2150 BCE. A full account of its form and possible significance can be found in Ray, K., Archaeology of Herefordshire (Logaston, 2015), pp.87-88.

Other reading

Devereux, P. Sacred Geography: Deciphering Hidden Codes in the Landscape. Octopus 2010

Gardiner, P. and Orborn, Gary. The Serpent Grail. Watkins 2005

Guthrie, S. Faces in the Clouds. A New Theory of Religion. Oxford Univ. P 1989

Miller, H. and Broadhurst, P. The Sun and the Serpent. Pendragon1989

Michell, John. Simulacra: Faces and Figures in Nature. Thames and Hudson 1979.

Published in NE163 (March 2021), pp14-21