Victoria and Paul Morgan help raise Cheshire’s prehistoric profile

INTRODUCTION

Cheshire is not a county famed for it its prehistory. At a push the megaraks can only really name The Bridestones (the remains of a Neolithic long cairn near the town of Congleton), but even that is often listed as belonging to Staffordshire.

The purpose of this article is to highlight one particular E Cheshire monument that has evaded the attention of many modern researchers and seemed to defy satisfactory classification, perhaps until now.

As you will read, The Bullstones did not escape the delicate touches of a 19th century antiquarian but beyond this much has remained theoretical. The odd arrangement of millstone grit cobbles and single monolith is scheduled. The County Sites and Monuments Record (CSMR) indicates that it is a round barrow, but it is like no ordinary round barrow and may soon come under scrutiny from one of prehistoric archaeology’s leading researchers.

The Bullstones can be found high above the town of Macclesfield on the S boundary of a moor called

Cessbank Common (NGR SJ95576761) but it is not marked on any OS map. Close to the village of Wincle, the stones sit just off a public right of way a couple of hundred metres from a convenient lay-by. If you visit the site and work up a thirst two pubs are located within a kilometre – The Hanging Gate to the N and The Wild Boar to the S.

Geographically and topographically this site lies within the Peak District National Park. It is itself part of a wider Bronze Age monumental landscape found in east Cheshire but is generally overlooked as being part of the Peak District.

ANTIQUARIAN REFERENCES

So far we have only given a vague clue as to the appearance of The Bullstones, but to visualise the site properly we need to take a look at the early descriptions.

The Bullstones first came to the attention of one Dr John Dow Sainter in the 1870s. When Dr Sainter (field surgeon, apothecary, geologist, naturalist and archaeologist) published his Scientific Rambles Round Macclesfield in 1878, this is what he found on the edge of Cessbank Common:

…a stone circle twenty feet in diameter, with apparently a headstone, more or less mutilated, four feet in height and the same in breadth, placed not in the centre of the circle, but between two and three feet to one side of it, northwards. Directly opposite the headstone, the circle was entered northward by a short avenue of stones; a line of stones also ran up to the circle in an oblique curve from each corner stone at the entrance to the avenue, leaving a small semi-triangular space on both sides…”

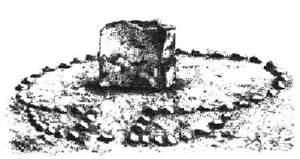

Sainter does not commit himself as to the purpose of the two triangles either side of the entrance (“…a fanciful addition to the to the avenue, or for a religious purpose”) but he does note that they are large enough “to accommodate four or five persons standing upright in each”. Sainter did investigate the triangles – “upon a trial being made with a spade no burial was found in either of them.” The publication contained his sketch of the site (Fig. 1).

Sainter worked closely with the Macclesfield Scientific Society and during these excavations an interment, that of “a child or young person”, was unearthed. An associated urn which he describes as being of Celtic-type and inverted, a calcined flint knife and a flint arrowhead were found with the burnt remains. He attributed the burial to the Romano-British period from “a time when a few of that [Celtic] race still lingered on those lonely and barren hills”.

Interestingly an urn, reputedly from The Bullstones, resides in the basement of the Congleton Chronicle’s offices awaiting re-homing in a local museum, should Congleton ever get one.

The next description of any significance (although a local historian, Rowley (1982) did discuss the site in a brief guide to the prehistory of Macclesfield) appeared in the Victoria History of the County of Cheshire (Lockley, 1987).

This work compares The Bullstones to other sites in Cheshire that contain stone settings (namely the ring contained under the Church Lawton III barrow near Crewe, a barrow near Warrington and a site in Delamere in the heart of Cheshire). Lockley suggested that all these sites ‘may be a development of free-standing stone circles of primarily ceremonial rather than burial function’.

As an aside, an attempt was made in 1984 to excavate The Bullstones. Archaeologists planning the dig had actually turned up on site and were about to break ground when the landowner changed his mind and withdrew consent at the last minute.

TODAY

Things have changed slightly since Sainter’s day. We first visited the site in February 2001 just before the Foot and Mouth epidemic took hold. We were not hopeful of locating anything easily because of the reference in the Victoria County History notes that the stones are ‘obscured by vegetation’.

However after only a short walk crossing two stiles, the standing stone soon became visible on the horizon above.

This was a good sign and having crossed a third stile and taken a route up a slope we were pleasantly surprised by what we found.

The most striking feature is a central standing stone which dominates the monument. It is a square looking monolith measuring 1.40m wide, 0.70m deep and 1.10m tall. Its ‘flat’ top contains a bowl-shaped depression formed along the stone’s natural bedding, similar to the weathering ‘bowls’ found on many standing stones found in this region.

This ‘headstone’ sits in a rough oval of cobble-sized stones (overall dimensions 2.8m by 2.5m, including the ‘headstone’). This paved area is absent from Sainter’s sketch and description.

Surrounding the stone is an incomplete outer ellipse of rounded cobble to small boulder-sized stones with a diameter of 7.9m x 8.5m which appears to mark the perimeter of a small platform (Fig. 3). Parts of this ring are barely visible and can be followed or inferred through the encroaching grass.

The entrance avenue, as described by Sainter, is difficult to make out as a mass of small boulders is found today, but a few minutes spent with Scientific Rambles can unravel the mess (compare Figs 1 and 2).

The ring and standing stone are located on the eastern flank of Brown Hill with an uninterrupted view through approximately 180 degrees. It would seem that any view to the W of the monument was not as important, as Brown Hill itself blocks this panorama.

However the view to the N, E and S is stunning. This takes in sweeping moorland and the summits of Shining Tor and Shutlingsloe to the NE and the outcrop of The Roaches and Hen Cloud to the SE.

Shutlingsloe and The Roaches are very prominent in the landscape (Shining Tor, despite being higher than Shutlingsloe, is really a smooth ridge rather than a summit).

As mentioned, The Bullstones’ standing stone is rectangular and therefore has a number of ‘faces’ that could hold alignments. The long axis of the stone appears to be orientated to ~128o in the direction of Roach End (the N tip of The Roaches outcrop). The sight line takes the eye across the Dane valley, over Back Forest (where Lud’s Church gorge is situated) and on to the N end of the millstone grit ridge.

The north-eastern long plane of the ‘headstone’ is orientated in the direction of Cessbank Common, past the characteristic summit of Shutlingsloe to the smooth featureless ridge of Shining Tor (the highest peak in the area) at an angle of ~38o.

The SW face of the stone points to the flank of an adjacent hillock (further suggesting that this outlook was not considered as important as the one to the E), with the southerly end of Wincle Minn being visible.

As mentioned, The Bullstones is not an isolated prehistoric feature in this landscape. Our recent researches have pulled together a gazetteer of finds, barrows, standing stones and earthworks which indicate that although somewhat overlooked, this part of E Cheshire is closely linked with the Neolithic and Bronze Age ritual activity in the Pennine region.

DISCUSSION

During our research both in Cheshire and the Peak District (Morgan, 2001) we have come across no other monument quite like this one.

The Bullstones is an enigmatic monument set in a spectacular location – this cannot be doubted. However until now the site has evaded modern attention so no satisfactory description as to what The Bullstones actually is has been forthcoming. Without the benefit of full academic enquiry the following interpretation may not be confirmed.

To start with, let’s look at what The Bullstones is not. The Cheshire CSMR classifies it as a round barrow. A note accompanying the record states that there are “some indications that there was formerly a round barrow or cairn”. Indeed Dr Sainter also postulates this when he suggests that the circle and standing stone may have been enclosed in a “tumulus ten or twelve feet in height, with the circle of stones placed round its base”. But he also suggests that the stone could have been part of a larger menhir, or part of a small cistaven or that perhaps there was no tumulus or mound placed over it at all.

There are many round barrows in this region and they all look as one has come to expect – grassy humps in fields. But could agriculture and the weather have played their parts in destroying this mound so completely?

Stone circle near Clulow Cross (J D Sainter)

Stone circle near Clulow Cross (J D Sainter)

It could be argued that if a mound of earth had enclosed the whole then there would be evidence of soil within the

cobble ‘nest’ around the base of the standing stone. The area is in the heart of drystone wall country so it is feasible a stone mound could have been robbed but, if this was the case then why was suitable stone left in the cobble ‘nest’? In addition the topographical position of the ‘barrow’ is such that ploughing on surrounding slopes would have been difficult.

Lockley classifies the site as a kerb circle – a cairn with a closely packed ring of boulders around the perimeter. This is fairly close to the description of The Bullstones but any cairn is absent and does not take into consideration the ornate entrance or standing stone.

So we can confidently say that The Bullstones is not a round barrow, but it could be some form of hybrid kerb circle. However there is ‘tradition’ of megalithic architecture particularly concentrated in one area over 250 miles away recently highlighted to us (Barnatt, 2001) which may hold the key.

The south-west Scotland area west of Kirkcudbright is home to a number of centre-stone circles, the best example being Glenquickan.

Reading the description of Glenquickan one gets the feeling of deja-vu. This site “is composed of twenty-nine very low, closely set stones in an ellipse…” with an “apparent gap in the ring at the south-west filled by a stone whose tip just shows above ground. The interior of the ring is tightly laid with small stones like cobbling” (Burl, 1995). This description continues “At the middle of the circle is an immense upright pillar…”.

Compare this description with Sainter’s and his sketch and you will note some striking similarities – even down to the ‘hidden’ cobble in the entrance.

In his 2000 volume Burl expands his description and explanation of centre-stone circles. He states “circles with

centre stones appear to be late and frequently have a cremation deposit at the foot of the centre stone…” and

that “the circles are composed of unobtrusive, rounded stones whereas the interior pillar is distinctly bigger.” He adds “such monuments can never have been conspicuous and were probably for local ceremonies”.

When Figure 1 and 2 are compared with pictrues of Glenquickan (for example that in Cope, 1999) the striking

similarities between the two site can be clearly seen. The Bullstones appears to be the ‘baby brother’ of Glenquickan as the ellipse is about half the size and the central stone is about half the height. The only difference between the two is the ornateness of The Bullstones entrance and the closer packing of the perimeter ring of cobbles. More generally The Bullstones share the tradition of placing a cremation under the central stone as mentioned by Burl.

As an interesting aside – not far from Glenquickan are located a number of Neolithic Clyde cairns with their characteristic semi-circular forecourts and horned cairns. Ten kilometres south-west of The Bullstones is located The Bridestones, a ruined long cairn with close affinities to these Clyde cairns.

So do we have the answer? Is The Bullstones a centre-stone circle akin to those found in south-west Scotland, Shropshire, Wiltshire, south-west Ireland and Cornwall? If it is this then this ignored site is quite unique in the Peak District and northern England and requires the addition of a new triangle to the distribution map of these monuments (Burl, 2000).

However Vicky and I must not get carried away. Following a long discussion with John Barnatt (Senior Survey Archaeologist with the Peak District National Park and stone circles expert) we gave him two pictures and a write up on the monument. He recently visited the site and his preliminary thoughts are that being composed of ‘a combination of ubiquitous single standing stone, and platform cairn the site truly does not fit with ‘normative’ typologies’. He calls it ‘a truly cracking site’.

There can be no doubt that this particular monument was important – the interment, urn and artefacts tell us that.

Clearly the surrounding landscape was also significant to Bronze Age man who would surely have been aware of other monuments close by (such as the now lost sites of the Henbury stone circle (Burl, 2000 and Rowley, 1982) and the Gawsworth henge (Rowley, 1982) both within the Borough of Macclesfield). But how a possible link with south-west Scotland or even Shropshire was made we will never know.

Whatever this site turns out to be it is a wonderful yet much ignored location with stunning views of the Peak District. I would recommend to anyone that they visit The Bullstones (if only briefly) if they are in Macclesfield and enjoy the stones and the place.

REFERENCES

Barnatt, J. 2001. Personal communication.

Burl. A. 1995. A Guide to the Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany. Yale Univ. Press.

Burl, A. 2000. The Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany. Yale University Press.

Longley, D.M.T. 1987. ‘Prehistory‘. In C.R. Elrington (ed). A History of the County of Chester, Vol 1. London: Victoria County Histories.

Morgan, V.B. and P.E. 2001. Rock Around the Peak: megalithic monuments of the Peak District. Sigma Press.

Rowley, G. 1982. Macclesfield in Prehistory.

Sainter, Dr J.D. 1878. The Jottings of Some Geological, Archaeological, Botanical, Ornithological, and Zoological Rambles Round Macclesfield. Macclesfield: Swinnerton and Brown, Printers. Repub. Silk Press Ltd 1999 (ISBN 1 902685 02 4) in limited numbers but still available.

Paul and Victoria Morgan are the authors of ‘Rock Around the Peak’, a guide to prehistoric sites in the Peak District , published by Sigma and reviewed in NE87.

Published NE90, Summer 2002, pp16-21

https://northernearth.co.uk/subscription-2024/