We frequently hear the word ‘shamanism’ bandied about in the context of prehistoric and tribal religion, and even in the context of witchcraft and modern contemporary trance techniques. But how far, really, does this all-encompassing idea of shamanism take our understanding of the phenomenon itself? We asked Alby Stone to comment.

Since about 1950, shamanism has often been cited by scholars – some more successfully than others – attempting to unlock the secrets of obscure European ritual objects and practices, ancient myths and legends, and archaeological sites.

For instance, in 1957 E.O. James suggested that the therianthropic ‘sorcerer’ depicted in the cave art of Les Trois Fréres was a shaman, wearing a costume akin to those of recent Siberian history or in the process of transforming into an animal. This idea was taken up by others, including Makkay in 1963 and Lommel in 1967. Dodds identified a shamanic element in Greek religion and philosophy. Ross saw a parallel between druids and shamans. Tolstoy argued that Merlin was a shaman. Norse scholars such as Dag Strömbäck linked shamanism with the cult of Odin. The idea of the witch as shaman was implicit in Murray’s work on witchcraft and has resurfaced regularly – Ginzburg traced ideas of the witches’ sabbath to an ecstatic tradition that stretched back to the shamans of the Palaeolithic caves, while Wilby has seen shamanistic elements in accounts of British witchcraft. Miranda and Stephen Aldhouse-Green have treated shamanism as a major factor in pre-Christian religious and ritual contexts in European archaeology [1].

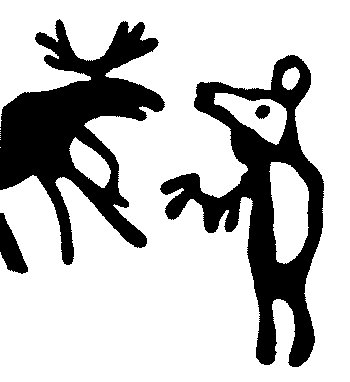

Two therianthropic figures from the palaeolithic art of Les Troise Freres cave; on the left is Abbe Breuil’s famous but flawed ‘shamanic’ figure.

Interest in shamanism among archaeologists and prehistorians has expanded and accelerated rapidly since the mid-1980s. This burgeoning interest in shamanism as a major component of ancient European religion is largely due to David Lewis-Williams, whose studies of southern African rock art in the context of San beliefs and rituals led him to conclude that prehistoric rock art arose from the visions of entranced shamans. Abstract patterns and images of cave art are elaborations of patterns and visual effects – known as ‘phosphenes’, ‘entoptic’ images or ‘form constants’ – hard-wired into the human nervous system. They occur as visions in various stages of trance induced by ritual dance, sensory deprivation or the ingestion of hallucinogens. Other images, such as elongated or apparently flying people and animals, are visual representations of physical sensations experienced during trance. This is now arguably the prevailing explanation of rock art among archaeologists. Recently, Lewis-Williams has extended the scope of his shamanic interpretation of rock art from the Palaeolithic to the Neolithic, particularly looking at the decoration and function of chambered stone structures [2].

At first sight, Lewis-Williams seems to have identified a ‘smoking gun’ that proves that shamanism was indeed the religion of Palaeolithic Europe. Plenty of archaeologists have accepted his ideas, which if true would add support to those earlier scholars who have seen evidence for shamanism in their own fields.

But it is by no means cut and dried. In the first place, Lewis-Williams and many other Anglophone scholars have an imprecise idea of shamanism. In the course of the 20th century, the name ‘shaman’ was increasingly applied to all kinds of magical practitioner: sorcerers, witches, priests, poets, seers, diviners and healers. In part this was due to sloppy scholarship, but it has been exacerbated by a growing tendency to remove supposedly pejorative terminology from academic debate (Terms such as ‘witch-doctor’ and ‘medicine man’ are hardly ever used academically these days, but they are often near-literal translations of native names). Shamanism is a phenomenon first recognised among the Evenk of Siberia, from whose language the word šaman was appropriated as a generic label for similar practitioners among neighbouring or related peoples. Some Westerners – such as Ronald Hutton and Alice Beck Kehoe [3] – argue that the term should properly be restricted to the Evenk of Siberia, though they accept the use of the word ‘shaman’ to denote similar practitioners. This restriction has always been prevalent among anthropologists in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. In short, people who don’t do what a Siberian shaman does in the same way are not shamans and should be given a more appropriate name.

Russian anthropologists once used the term ‘shamanhood’ to denote the condition of being a shaman, with all that entails in the way of rite and social function – to emphasise that it is a ritual technique used by particular individuals within a variety of social and religious contexts and not a discrete religious ideology. This usage is gradually coming back into favour. In the West, the word ‘shamanism’ has come to imply a cohesive belief system with mystical experience at its core. This is almost wholly due to Eliade’s epochal study of shamanism, in which he included as shamanism belief systems that had at best only the flimsiest resemblance to the Siberian model. This was chiefly based on the idea of ecstasy. Eliade wanted to prove that ecstasy – mystical experience through altered states of consciousness – was a universal phenomenon, humanity’s ur-religion [4].

Ecstasy, trance or altered states of consciousness are central to both Eliade’s vision of archaic religion and Lewis-Williams’ interpretation of rock art as an expression of shamanic experience. Unfortunately for both, Siberian shamans do not usually undergo real trance. The use of hallucinogens is pretty rare and where they are used tends to be communal and mainly designed to prime the audience for supernatural phenomena. Furthermore, shamanic performance is complex and requires the shaman to be in complete control: performances include narrative, mimicry and ventriloquism, drumming, mime, song and legerdemain. Shamanising is a skilled and demanding enacting of otherworld journey, with the emphasis firmly on performance. There is no actual visit to other worlds – the main exception being shamans’ initiatory experiences, which normally occur as dreams or hallucinations during sickness. These factors alone are enough to demolish Eliade’s fantasy, and ought to deter archaeologists from labelling ancient trances as ‘shamanic’. More damagingly, Helvenston and Bahn (among others) have offered strong arguments against ‘entoptic’ rock art being down to trance [5].

Siberian shamanism has only been known to Europeans for about 500 years. Possible shamans are briefly mentioned in Chinese documents and European travellers’ tales before about 1500, but in little detail. Saami or Finnish shamans are described in Old Norse texts of the 13th and 14th centuries, but they and earlier mentions are usually brief and vague. Eskimo shamans have been studied for about as long as their Siberian counterparts. In short, shamanism as we know it is a modern phenomenon. And thanks to evangelical Christians, Stalinism and the lure of modern life, it is one that largely died out more than half a century ago. Thankfully, shamanic traditions and rituals were recorded by travellers, missionaries and anthropologists, and many shaman drums and costumes have been preserved in museums. But since the last generation of traditional shamans died out, hardly any shamans practising today are untainted by New Age ideas. In recent years Michael Harner’s foundation has been heavily involved in educating would-be shamans of the former Soviet Republics in how to ply their trade, and has a strong influence on local anthropologists. The revived practices have little to tell us about traditional shamanism.

This Siberian rock art, showing what appears to be a bear-headed human, dates from c3500 BCE

Another problem is that Siberian shamanism has clearly been subject to external influence. For instance, Evenk and neighbouring peoples’ shaman costumes have clearly accommodated elements of Lamaist dress, while local variants of the so-called shamanic cosmos reflect the influence of Buddhism and Islam. The extreme variation of shamans’ costume poses another problem: Eskimo and Saami shamanism shows no tradition of special costumes. It could be that these represent the most archaic form of shamanism, while their Siberian counterparts’ apparel is a late development.

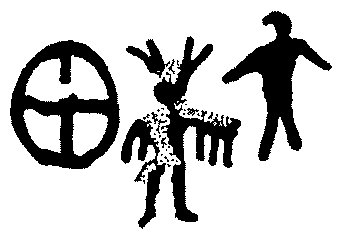

These figures, considered to be a shaman and a spirit helper, are from Siberian rock art of around 400 years ago

Obviously Siberian shamanism did not simply appear, fully formed, out of nothing. There must have been some early stratum of religion and ritual from which it developed. But we can only guess at what that proto-shamanism was like. Even in Siberia there is precious little evidence for prehistoric shamanism. Mihály Hóppal and Ekaterina Devlet have observed that the earliest probable depictions of shamans or shamanic ritual (as rock art, ironically) date from around 2000 BCE. Anna-Leena Siikala has interpreted Finnish rock art that may be as old as 3000 BCE as evidence for shamanism, but a shamanic provenance is debatable [6]. Elsewhere, there is nothing of greater antiquity that can unequivocally be called shamanic. Whether or not so-called shamanic elements of African and European rock art are derived from trance along the lines suggested by Lewis-Williams – irrespective of the arguments against that idea – authentic altered states of consciousness are not part of the ritual technique found in Siberian shamanism and its analogues. We cannot date shamanism by evidence for trance.

Nor can we estimate the antiquity of shamanism from the type of culture in which it is found. While received wisdom has it that shamanism is a religious form proper to nomadic hunter-gatherers, the simple fact is that most shamanist peoples in Siberia live by herding reindeer and subsistence farming – and have done since records began. With the Eskimo and a handful of other peoples in the north circumpolar region, hunter-gatherers and other ‘Stone Age’ peoples do not have anything that is remotely like Siberian shamanism. Yet shamanism is consistently projected back to Palaeolithic Europe.

The theory of Palaeolithic shamanism is based on a crude logic. Primitive is the same as archaic; shamanism is a primitive technique, therefore it is very old. Siberian shamanism was considered primitive as soon as Europeans began studying it in a scientific way, as Czaplicka’s survey of 19th-century Russian scholarship makes abundantly clear [7]. Shamanism was a primitive form of worship among primitive peoples. We no longer use the word ‘primitive’, but it has been replaced by a raft of unsatisfactory euphemisms – ‘indigenous’, ‘tribal’, ‘pre-literate’, ‘pre-technological’ and so on – that all really mean the same thing: unevolved people who have yet to attain a level of cultural sophistication comparable to our own. It is basically getting the idea of ‘primitiveness’ in through the back door.

At the last we are left with no reliable way of ascertaining the antiquity of Siberian shamanism, and no way of ascertaining whether ancient ritual in Palaeolithic Europe was shamanic, except in the most watered-down and meaningless sense. Undoubtedly, authentic shamanism was present in ancient Europe. Iranian-speaking steppe nomads (Scythians, Alans, Sarmatians, and so on) who may have been shamanists were in contact with Eastern Europe from at least 500 BCE and made deeper inroads soon after, followed by shamanist Avars, Magyars and Turks. The Finns and Saami settled in Finland and the north of Norway and Sweden several millennia ago; their shamans were known to the Norse and inspired many of their tales of witches and wizards. One or more of these groups may have transmitted their rites and beliefs to the peoples already living in Europe, descendants of the first waves of Homo sapiens to settle the continent after the last Ice Age. But whether any kind of home-grown European shamanism ever developed independently has yet to be established.

Notes

We frequently hear the word ‘shamanism’ bandied about in the context of prehistoric and tribal religion, and even in the context of witchcraft and modern contemporary trance techniques. But how far, really, does this all-encompassing idea of shamanism take our understanding of the phenomenon itself? We asked Alby Stone to comment.

References

[1] Miranda and Stephen Aldhouse-Green, The Quest for the Shaman, Thames & Hudson, 2005. E.R. Dodds, The Greeks and the Irrational, Univ. California Press, 1951. Carlo Ginzburg, Ecstasies, Hutchinson, 1990 (Italian ed. 1989). E.O. James, Prehistoric Religion, Thames & Hudson, 1957. Andreas Lommel, Shamanism: The beginnings of art, McGraw-Hill, 1967. Janos Makkay, Two Studies on Early Shamanism, J. Makkay, Budapest, 1999. Margaret Murray, The God of the Witches, OUP, 1933. Anne Ross, Pagan Celtic Britain, 1967, 2nd ed. Constable, 1992. Dag Strömbäck, Sejd, Hugo Geners Förlag, 1935. Nikolai Tolstoy, The Quest for Merlin, Little, Brown & Co., 1985. Emma Wilby, Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits, Sussex Academic Press, 2005.

[2] David Lewis-Williams, The Mind in the Cave, Thames & Hudson, 2002. David Lewis-Williams & David Pearce, Inside the Neolithic Mind, Thames & Hudson, 2005.

[3] Ronald Hutton, The Shamans of Siberia, Gothic Image, 1993. Alice Beck Kehoe, Shamans and Religion, Waveland Press, 2000.

[4] Mircea Eliade, Shamanism, Princeton Univ Press, 1964.

[5] Patricia A. Helvenston & Paul G. Bahn, Desperately Seeking Trance Plants: Testing the ‘three stages of trance’ model. RJ Communications LLC, 2002.

[6] Ekaterina Devlet, ‘Rock art and the material culture of Siberian and Central Asian shamanism’, in Neil S. Price (ed.), The Archaeology of Shamanism, Routledge, 2001. Anna-Leena Siikala, ‘Finnish rock art, animal ceremonialism and shamanic worldview’ and Mihály Hóppal, ‘On the origin of shamanism and the Siberian rock art’, both in Siikala & Hóppal, Studies on Shamanism, Akademiai Kiado, Budapest, 1998.

[7] Marie Antoinette Czaplicka, Aboriginal Siberia, OUP, 1914.

Published in NE111 (Autumn 2007), pp.9-12