Robert W E Farrah looks into the esoteric furore ignited by a new public artwork in Carlisle

The curse

In the very heart of the city of Carlisle, as the new millennium was beginning, a tale of the supernatural was unfolding which would be worthy of the wild imaginings of many a horror writer. Word spread of an occult ritual being carried out on the streets of Carlisle and eventually reached the national newspapers, with headlines such as ‘Archbishop to lift ‘evil’ curse linked to foot and mouth’1, ‘Bishop tries to lift curse blamed for causing foot and mouth’2. These concerned a sculpture commissioned by Carlisle City Council, the ‘Archbishop’s Stone’, which more informally became known as the ‘Cursing Stone’ and became the centre of accusations of satanic rituals.

The reason for considering the spiritual controversy surrounding the Archbishop’s Stone is in affording a better understanding of the perception of sacrilege and desecration to our ancient sacred sites. A perception which is perennial – constant to spiritual time.

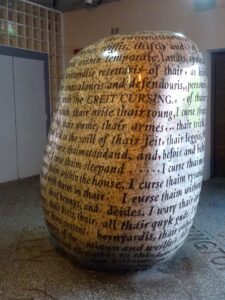

The Archbishop’s Stone and the ‘Reiver’ pavement on which it is sited form a complete artwork, commissioned as part of the City Council’s millennium project, and was to be the centrepiece of a new £6.7 million exhibition (see Note). The Stone started life as a glacial granite boulder from Galloway, weighing 12-14 tonnes. It was then carved towards a sphere and finally reduced to a more natural shape resembling a beach pebble weighing approximately 7.5 tonnes. The completed sculpture is 1.75 m high and 1.5 m diam. The ‘Reiver’ pavement is a type of granite known as French Tarn, which has a light brown fleck to echo the steel wall of the Millennium Gallery. It is inscribed with the names of the reiving families, almost all of the inhabitants of the Borders in the 15th-16th centuries. The pavement has a wandering trail design leading towards the Stone. The artwork is housed underground in the public subway beside the Millennium Gallery. This subway connects Carlisle’s Tullie House museum with the castle; this site was a water-filled ditch in medieval times, separating the town from the Castle.

The ‘Archbishop’s Stone’ (hereafter referred to by the more descriptive ‘Cursing Stone’) is inscribed with part of a curse written in 1520 by the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Glasgow, Gavin Dunbar. The curse excommunicates the ‘common traitors, reivers and thieves’ dwelling in the Scottish Middle and West Marches of the Anglo-Saxon Border. The reivers were English and Scottish rustlers and robbers who terrorised the border regions with systematic raiding, blackmail, kidnapping, arson, extortion and internecine murder, in a region of total lawlessness. The curse was written in a southern Scottish dialect and is one of the longest on record, running to over 1500 words, and has never been revoked. It was read aloud to congregations from pulpits of every parish within the border regions.

The ‘Cursing Stone’ is inscribed with just a fragment of the full curse, amounting to 383 words using ‘Benbar’ font, an appropriate antiquarian script. As a visual artist and not a writer Gordon Young did not feel inhibited by the editing of the text for the sculpture. The text was chosen in a ‘…relaxed, subjective manner…it was, I like this…it’s powerful…I just wanted the stone, the sculpture (surrounded by the swimming pool of names), to echo and transmit the qualities, the passion, of the content’3. The text is continuous and runs in horizontal lines anti-clockwise around the stone, with arrows pointing down to indicate where a sentence is continued onto the next line. The inscription commences at the top of the stone with part of a sentence from near the end of the written curse. It then continues with a proclamation and declaration, before becoming a repetitive rant against the reivers. The Telegraph’s description of a ‘colourfully worded curse’ is an understatement – the curse is a masterful piece of venomous rhetoric which in its chant-like rhythm still makes a powerful impression:

…to be hang syne revin and ruggit with doggis, swyne, and utheris wyld beists, abhominable to all the warld. I denounce, proclamis, and declaris all and sindry the committaris of the said saikles murthris, slauchteris, brinying, heirchippes, reiffis, thiftis and spulezeis, oppinly apon day licht and under silence of nicht, alswele within temporale landis as kirklandis; togither with thair part takaris assistaris, supplearis, wittandlie resettaris of thair personis, the gudes reft and stollen be thaim, art or part thereof, and their counsalouris and defendouris, of thair evil dedis generalie CURSIT, waryit, aggregeite, and reaggregeite, with the GREIT CURSING. I curse their heid and all the haris of thair heid; I curse thair face, thair ene, thair mouth, thair neise, thairg toung, thair teith, thair crag, thair schulderis, thair breist, thair hert, thair stomok, thair bak, thair wame, thair armes, thair leggis, thair handis, thair feit, and everilk part of thair body, frae the top of their heid to the soill of thair feit, befoir and behind, within and without. I curse thaim gangand and I curse thaim rydand; I curse thaim standand, and I curse thaim sittand; I curse thaim etand, I curse thaim drinkand; I curse thaimwalkand, I curse thaim sleepand; I curse thaim rysand, I curse thaim lyand; I curse thaim at hame, I curse thaim fra hame; I curse thaim within the house, I curse thaim without the house; I curse thair wiffis, thair barnis, and thair servandis participand with thaim in their deides. I wary thair cornys, thair catales, thair woll, thair scheip, thair horse, thair swyne, thair geise, thair hennys, and all thair quyk gude. I wary their hallis, thair chalmeris, thair kechingis, thair stanillis, thair barnys, thair biris, thair bernyardis, thair cailyardis, thair plewis, thair harrowis, and the gudis and housis that is necessair for thair sustentatioun and weilfair. All the malesouns and waresouns that ever gat wardlie creatur sen the begynnyng of the warlde to this hour mot licht apon thaim. The maledictioun of God, that lichtit apon Lucifer and all his fallowis, that strak thaim frae the hie hevin to the deip hell, mot licht apon thaim. The fire and the swerd that stoppit Adam far yettis of Paradise, mot stop thaim frae the gloir of Hevin, quhill thai bere and mak…

Young, a Carlisle-born artist, was the lead artist appointed to Carlisle’s Millennium Gateway Project. His brief was broad, essentially being asked to respond to the character of Carlisle and its history. He is from a Border reiver family – between him and his wife they have “six family names linking us to the Reivers”4. Young produced three concept books for the project. As a full-time sculptor, he has had an interest in locating his artwork in appropriate settings. So the ‘Cursing Stone and the Reiver Pavement’ became located at an important time in a location of cultural and historic significance, which is still a site of civic importance. A criticism is that there is no information provided to explain its purpose and for many passing by it is difficult to comprehend. Young believes that this lack of explanation is acceptable; “works of art communicate in their own way…a ‘definitive’ plaque can be a crutch…”5. The artwork is purposefully multi-layered, allegorical and open to interpretation, yet some elucidation of its purpose can be reliably expressed. There is a certain physicality of movement in the sculpture from the direction of Tullie House Museum towards the Castle. This movement is incorporated into the pavement, which is inscribed with reiver names and flows wave-like towards the Cursing Stone. The names begin to fade on the pavement in the vicinity of the Stone, which is sited where the subway emerges into the light. This is where the main aspect of the Castle is first seen and where many of the reivers were imprisoned. The Castle and the Cursing Stone can be seen as representative of secular and spiritual authority. The Castle was the seat of law and order at the time of the reivers, while the curse was issued by ecclesiastical authority. The setting of the artwork evokes images of a people bound and imprisoned by both the words of an excommunication and the stone walls of a Castle. Young acknowledged the historic context but also pointed out the contemporary context of the Castle as County Record Office, with the interest in genealogy – symbolic of the future – and Tullie House Museum as memory – symbolic of the past.

This artwork has acquired an aura of darkness due to a campaign by a small but vocal minority, all from the Christian community; without this campaign, to have the sculpture removed or the curse revoked, there would have been no news story and no media interest. Carlisle City Council was accused of commissioning a piece of ritual magic capable of ‘spiritual violence’, masquerading in the guise of art. It has been stated quite correctly that the Cursing Stone’s inscription invites the tourist and the visitor to participate in an occult ritual. To read the curse, they must walk around the stone in an anti-clockwise direction – widdershins, or withershins, meaning a direction contrary to the course of the sun, a practice well documented in occult circles and “some Christians believe the power of the curse has been maintained”2 by this ritual. It has to be said however that it was never consciously intended by the artist or Carlisle City Council to create a sculpture that would recreate a form of occult ritual.

The Bishop of Carlisle, the Rt. Rev Graham Dow, has given vocal support to the campaign, “backing local Christians who believe that the curse exerts a malevolent influence”1. The Bishop has dismayed local councillors by disclosing his intention to invite the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Glasgow to bless the stone in a ceremony of exorcism, lifting the curse invoked by his predecessor, stating that he believed that the curse still contained ‘spiritual power’. Dow has said “I understand that it is a piece of history and it is reasonable for it to be known about, but the words have power and inasmuch as the curse wishes evil on people it should be revoked…If it has to stay I would prefer a blessing to offset it. We can’t treat it as just a joke. People have differing views about spiritual power and its capacity to do evil, but I am sure that it is a real force”1. The spiritual premise of Bishop Dow’s words are perennial and have a resonance throughout the world’s faiths.

Bishop Dow’s comments support the claims of the Rev Kevin Davies, the vicar of Scotby and Cotehill with Cumwhinton, who famously blamed the curse for the outbreak of foot and mouth in the region. Mr Davies has called the curse “a violent piece of spiritual language”. The outbreak of foot and mouth is only one manifestation offered as evidence of the spiritual malevolence of this curse. Bishop Dow’s invitation to the Archbishop of Glasgow to exorcise the curse was originally extended by the previous Bishop of Carlisle (Ian Harland), who initially supported the stone until the Cumbrian Christian magazine Bound Together campaigned against it. However, the Cardinal Bishop of Glasgow, Thomas Winning, has since died of cancer. The Bishop of Lancaster, John Brewer, is another high-ranking dignitary to have condemned the Project because of its perceived association with the occult. He also died of cancer shortly afterwards6.

Councillor Judith Pattinson told the BBC’s Today programme in a pointedly blunt response that the curse was just “words very nicely engraved into a huge lump of granite. It is a wonderful thing for visitors to come and have a look at – a fine piece of art”. A similar response came from a council spokesman who stated that the Council took Bishop Dow’s concerns seriously, but “we do not regard the stone as evil. We regard it as a work of public art”1.

There does seem to be some justification for this response. The full text of the curse has been in print for the last 30 years as an appendix, ‘The Archbishop of Glasgow’s ‘Monition of Cursing’ against the Border reivers’, in the widely-read Steel Bonnets7. David Clarke, Senior Curator & Collections Manager of Tullie House Museum, has informed me that ‘part of the curse has been reiterated many times daily over the past ten years in the audio-visual presentation at Tullie House – all without evident concern’8.

The ‘cursing stone’ was only one of many proposals in the Carlisle Millennium Project. The Christian campaign also accused the Council of trying to introduce pagan and occult symbolism into what should be a celebration of 2000 years of Christianity. Bound Together has been one of the main campaigners. The elders of the Council were also charged with introducing ‘dark elements’ into the Project – a pyramid and the City’s Millennium logo, a 2nd century pagan god. The glass pyramid was a key element in the original plans for the Millennium Gallery development. This proposal fell through due to local political protest. David Clarke suggests that the reason for this was very likely more “innate conservatism…and a failure to accept new and radical architecture, rather than religious views…”; its inspiration was not influenced by religious motives. The City’s Millennium logo was a graphic created by a local designer for promotional purposes which Clarke states was “…rather abstract – any connection with pagan gods was extremely loose, and certainly never expressed consciously”. He states that these themes were originally introduced to the Project to “recall genuine historic finds which show that a ‘spirit of place’ was important to earlier peoples”, not to promote paganism9.

Disturbingly, evidence is again provided showing that it can be “no coincidence that those who have boldly opposed the Project have come under sustained attack by the enemy”10. These seemingly latter-day Christian martyrs were businessman David King, a leading campaigner against the pyramid, who became seriously ill with a brain tumour, and the Rev Robert Ireton, who condemned the use of the pagan god as the Millennium logo and also became seriously ill6.

There is an irony apparent here: the Cursing Stone and Reiver Pavement, incorporating the symbolism of darkness and light, is being accused of representing the forces of evil by some of the Christian community. Prior consultation with the Church did take place and Young did research the theological position on Church doctrine. Young, in attendance with the Director of Development, met the then Bishop, Ian Harland, the Dean and the Rev Pratt, who “outlined their concerns, which came mostly from Leslie Irvine and the press”11. According to Irvine, both the Bishop and Pratt “were asked for their guidance whilst the stone was on the drawing board and offered no resistance to it”10. The concerns of the Church were that Christianity was not suitably represented in the Project, which was a celebration of the Millennium and 2000 years of Christianity.

Young was also invited to address a meeting of Church elders from various denominations in Penrith. He gave a considered response based on research into theological doctrine, quoting from works by The Reverend Dr Walter Brueggemann, Professor of the Old Testament, and Matthew Fox, an ordained priest since 1967 and described as a “liberation theologian and progressive visionary”. Brueggemann suggests that “neither blessing nor cursing in the Bible is spiritualized or religious”; rather, both “were concerned with the socio-economic, political and material welfare of the community”12. To Young this seemed to be the intent of both Archbishop Dunbar and many of the contemporary Church leadership at the meeting who “held a similar view”. The blessing was as important a component as the curse to the Project, but “never seemed to arouse anywhere near the same interest as the curse”13. It was not part of the original plans to place a blessing in the Millennium Gallery, but a solution was reached, with Young being asked to work with the Rev Pratt on a blessing to be eventually positioned on the pumphouse door in close (spiritual) vicinity to the Cursing Stone.

This meeting was to lead to a slide lecture given by Young at Tullie House where about 80 local Church leaders were in attendance. Young’s impression of this presentation was one of “very good support from some quarters”14. Not all were in accord, though, and there was some inevitable division. The response from Catholics seemed favourable; Young was also surprised by some support from the Quakers and the Church of Scotland. The Methodists were not supportive, but opposition came mostly from Irvine’s Church and some sponsors withdrew their financial support of the Millennium Project as a result. The theological doctrine and the position of the Church is not entirely clear and has not been adequately explained – it is likely that this will remain so. I was warned during my research that attempts to uncover the truth of the debate and piece together the whole story may prove unfruitful. With a conspiratorial air surrounding the Cursing Stone it has been suggested that there has been a ‘battening down of the hatches’ due to the pressures created by the campaign led by Irvine and others.

The evidence of the spiritual malevolence of this curse and the ‘martyrdom’ of those opponents who suffered ‘sustained attack’ is by nature highly subjective. It has been suggested that if the ‘qualifying period’ for an effect to be related to a supposed cause is unknown, then almost anything could be cited as evidence of the curse. There were after all many who opposed the Project who did not fall ill. The curse was invoked specifically against the reivers, so is it possible for divine retribution to be sanctioned upon those innocent of the charges for which the curse was invoked? The associations of cause and effect can be seen to be tenuous and seemingly only acquire a rational existence within the spiritual parameters of a belief system. It may be that the psychological seeds are very likely in the mind of the beholder and grow when supported by a faith system. It is a mindset present whenever we cross the threshold of what is perceived as sacred.

The traditions of ‘retribution’ upon those who desecrate ancient monuments is one such instance. The words of Bishop Dow would I suggest have been understood by those who left behind them the first consciously created monuments in the landscape. The sacred significance of those monuments is suggested to some by the invested labour resource which gave them the permanence of stone. Whether it be Mayburgh Henge15 or the Cursing Stone the same sacred order is present. It cannot be denied that evidence of such spiritual malevolence occurs with regular frequency throughout spiritual time. The claim that the Cursing Stone may renew the resonance of the curse, focused and maintained by the ritual (whether consciously intended or not), at a location where one emerges symbolically from the darkness (the subway), into the light, is entirely supported by occult and esoteric law.

Notes

The sculpture and the actual exhibition in the Millenium Gallery cost less than £0.5 million; the figure of £6.7 million included construction costs of the gallery and subway.

1. Daily Telegraph 11.04.01

2. Daily Mail 6.11.01

3. pers. comm.

4. pers. comm.

5. pers. comm.

6. http://www.b2gether.freeserve.co.uk/newsflash.html, 21/10/2001

7. George MacDonald Fraser, The Steel Bonnets; The Story of the Anglo-Scottish Border Reivers. Barrie & Jenkins 1971

8. pers. comm.

9. pers. comm.

10. http://www.b2gether.freeserve.co.uk/campaign.html – 21/10/2001

11. pers. comm.

12. Fox, M. Original Blessing. Bear & Co 1983:45; & Brueggemann, W. Tradition for Crisis : A Study in Hosea. John Knox Press 1968:69

13. pers. comm.

14. pers. comm.

15. R.W.E. Farrah, ‘The Legend of Mayburgh Henge’, NE91

My grateful thanks to David Clarke, Senior Curator & Collections Manager at Tullie House Museum; Gordon Young, sculptor and lead-artist to Carlisle City Council’s Millennium Project, for their correspondence concerning the issues of the Millennium Project and the Cursing Stone in particular. To Leslie Irving and his ‘Church’ for questioning both the civic and artistic interpretation and focusing on the occult issues of the Millennium Project and the Cursing Stone. To every Icarus who flies too close to the sun to create every wild work of the imagination – ‘in the jingle jangle morning I’ll be following you’.

Published in NE92, Winter 2002, p19-24