King Arthur has made his mark on Britain’s landscape, and not surprisingly left his name on numerous ancient sites. Here, Dave Weldrake considers Arthur’s relationship with Round Tables and maidens…

Arthurian place names

A lot of time and effort has been spent on trying to site the battles of King Arthur. (See for instance Alcock 1971, Ashe 1980 and 1987). The options are far too many and the evidence too scanty to make firm pronouncements. However, such researches tend to be based upon what, for lack of a better term, might be referred to as pseudo-history (Nennius and Geoffrey of Monmouth, for instance). Little account seems to have been taken of places suggesting an Arthurian connection by their name alone. This is in contrast to Robin Hood placenames, which seem to be much better documented (See Dobson and Taylor 1989).

The majority of the non-literary sources for Arthurian placenames can be divided into two groups, both of which can be paralleled elsewhere. The first group are those which make Arthur and his contemporaries out to be giants, capable of throwing huge rocks from one place to another. One example of this sort of tale comes from Sewingshields on Hadrian’s Wall, where Arthur is said to have thrown a boulder at Guinevere, who turned it away with her comb. Another is from Manchester, where Sir Tarquin, one of Arthur’s enemies, threw a huge rock at some of his opponents. This rock was later used as a plague stone, indentations in its surface being used to contain vinegar (Hardwick 1872). The same gigantic size has also been bestowed on Robin Hood in places too. He is, for instance, supposed to have flicked Robin Hood’s Pennystone, a huge glacial erratic on Midgley Moor (West Yorkshire), off the toe of his boot! It appears that heroes must always be larger than life.

The second group of stories features the sleeping knights, usually presumed to be Arthur’s warriors, although this is not always explicitly stated. The story of the wizard of Alderley Edge is well known – largely thanks to novelist Alan Garner – but there are also supposed to be caverns of sleeping knights under Richmond Castle (North Yorkshire) and Sewingshields Crag (Northum-berland). Again this type of tale can be paralleled elsewhere, both in the British Isles and abroad. Thomas the Rhymer is supposed to be sleeping under the Eildon Hills in Scotland, for instance, and Arthur himself is supposed to sleep on under Mount Etna (Hole 1948).

However, there is a third group of monuments bearing an Arthurian tag for which there would seem to be no close parallel. These are the ones which carry the name King Arthur’s Round Table or just The Round Table. The name clearly suggests a connection with the hero but its nature is not clear. The places themselves are disparate in nature and, as far as I know, no story to account for the Arthurian connection has survived.

The Round Table Sites

Geoffrey Ashe (1980) identifies five of these Round Table sites: Bwrdd Arthur (Arthur’s Table) on Anglesey is a hill fort; Bwrdd Arthur in Clwyd is a circle of holes cut into a hillside, presumably another prehistoric feature; the amphitheatre at Caerleon; an earthwork at Stirling Castle; and Mayburgh in Cumbria. In the latter case Ashe seems to be in some confusion, for he describes what seems to be the Mayburgh henge monument itself, whilst King Arthur’s Round Table is in fact a separate henge feature some distance away. There is also a second badly robbed circle associated with this group of monuments, the Little Round Table (R. W. E. Farrah, ‘Mayburgh Henge: a sacred space odyssey’, NE 85). I suspect that this list could be substantially lengthened. In A History of English Field Names, the aptly named John Field notes “Round Table occurs in Easington (Staffs), in Beausale (Warks) (Le Round Table 1554), in Ecclesfield (The Round Table Meadow 1660) and in Rotherham”. A couple of hours with the publications of the English Place Name Society also brought up a prehistoric cairn in Westmorland.

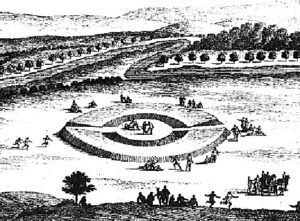

An 1833 ground-plan of maiden castle in Dorset (William Barnes)

Tournament Sites

One line of reasoning to account for the Round Table placenames is to suggest that they are places where tournaments imitating the acts of Arthur and his knights took place. This line of argument is developed by Jennifer Westwood to account for the names of both Pendragon Castle near Kirkby Stephen and for the Cumbrian Round Table itself. The castle was built by Robert de Clifford in the 1200s, but popular tradition ascribed its construction to Uther Pendragon, the father of King Arthur. Locally it would seem to have been judged an act of folly:

Let Uther Pendragon do what he can

The river Eden still runs as it ran

Westwood suggests that “he may have adopted the name ‘Uther Pendragon‘” during the Round Table tournaments and the castle acquired the name as a result. The Cumbria Round Table, she suggests, may have been the site of one of Clifford’s jousting tournaments. The explanation seems improbable, as Uther was not one of the Round Table Knights, but Arthur’s father, and I would suggest that an alternative be sought elsewhere.

In effect such reasoning as Westwood’s offers a similar argument to that used to account for the frequency of Robin Hood placenames in areas well outside the outlaw’s traditional haunts: Robin Hood was popular at May Day games and it is from this that we get the numerous Robin Hood’s Butts (examples in Cumberland, Herefordshire, Shropshire and Surrey) and Robin Hood’s Wells (two examples in Wharfedale alone). It might also account for the greater frequency of the Robin Hood placenames compared with Round Table ones. Anyone can go out on a May morning and pretend to be an outlaw in the greenwood, but going off fully armoured on a horse is the prerogative of the rich.

Imitating the fabled acts of the Arthurian Romances was certainly a favourite pastime among the knightly classes. Edward I, for instance, held a Round Table in 1284 at Nevin in Wales to celebrate his defeat of Llewellyn and the acquisition of the Iron Crown of King Arthur worn by the Welsh Prince. Another Round Table was held at Falkirk in the subsequent year (Pickford 1955). His grandson Edward III was so fond of Arthurian themes that, for a while, he contemplated setting up an order of chivalry based upon the Arthurian cycle. This plan eventually crystallised, without an overt reference to Arthur, into the Order of the Garter. An Edwardian Round Table tournament might therefore have been the origin of the Round Table now housed in Winchester Castle. On the basis of radio-carbon dating Martin Biddle suggests the date of 1290, which was the date of a feast held there by Edward I. This piece of furniture has clearly been refurbished at a later date with a Tudor Rose. This was perhaps carried out for some occasion celebrating the birth of Henry VII’s first son Prince Arthur.

A display of this sort may therefore be the origin of the Stirling earthwork. It is after all adjacent to a castle, the occupants of which may have felt the need for keeping in with the dictates of the latest fashion and would have had the finances to carry it out. It may also be the origin of the Ecclesfield example as there is a moated site nearby. However, the other examples would seem too remote to represent tournament sites and therefore an alternative explanation must be sought.

Stukeley’s 18th century drawing of King Arthur’s Round Table

Stukeley’s 18th century drawing of King Arthur’s Round Table

Mayburghs and Maiden Castles

A clue might be found in the name of Mayburgh itself. According to Smith (1967), the name is derived from the Old English word for maiden. It is therefore another example of the Maiden Castle placename, most familiar from the huge earthwork in Dorset, but which also occurs in Grampian, Durham, and Northumberland (Grinsell 1976) [There is also a Maiden Castle near Low Row in Swaledale, and other Maiden Castles are listed by Jeremy Harte in Cuckoo Pounds & Singing Barrows, Dorchester 1986, pp. 58-63. Ed]. It has been suggested that these features acquired their present names because they were places where women gathered for celebrations and festivities, for instance at May Day. If this is so, it becomes possible that what we have on the Mayburgh/King Arthur’s Round Table site is some form of gender division as to who uses the monuments. The men use the Round Table, the women use the Mayburgh/Maiden’s Castle. Perhaps there were even raids from one to the other. Something of the sort may also be implied in Leyland’s remark about Bwrdd Arthur in Clwyd that ‘there children and young men coming to seek their cattle used to sit and play’ (cited in Ashe 1980, p. 174). Mayburgh too seems to have been used for country sports during the 18th century (Westwood p. 387) and there is also a Mayfield at Ecclesfield as well as a Round Table Meadow.

The antiquity of the name

The question then arises as to what the former name of these sites might have been. Clearly a name such as King Arthur’s Round Table cannot have been given to a feature before the popularisation of the concept in Wace’s adaptation of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain in the mid-1100s. The first recorded usage of Round Table as a placename is not until a good deal later (1540 for the example adjacent to Mayburgh, 1669 for the Ecclesfield Round Table Meadow). Did the association perhaps come with a former placename containing the word king and Arthur added later? Certainly there are examples of anonymous kings giving their titles to prehistoric features. Two example in Northumberland are the Three Kings of Denmark and the Five Kings stone row (Burl, 1995 p. 72). Alternatively the roundness of the monuments could have given rise to the name, but if that is the case, why was the name not more often applied to other circular prehistoric features?

The mystery of the Round Table

Clearly there is a mystery here. Why has the Arthurian tag been applied to these monuments and not to others? Does he replace an older figure here, as presumably he did in the stone-throwing and sleeping hero incidents? If so, who was it? In the final assessment it seems we will never know. This is the real mystery of the Round Table.

Bibliography and References

Ashe, G., 1980, A Guidebook to Arthurian Britain.

Ashe, G., 1987, The Landscape of King Arthur.

Biddle, Martin, 2000, King Arthur’s Round Table.

Burl A, 1995, Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany.

Dobson, R. B., and Taylor, J., 1989, The Rhymes of Robin Hood.

Field, John, 1993, A History of English Field Names.

Grinsell, L. V., 1976, Folklore of Prehistoric Sites in Britain.

Hardwick, C., 1872 (reprinted 1973), Traditions, Superstitions and Folklore of Lancashire.

Hole, C., 1948, The English Folk Hero.

Pickford, G. E., 1955, ‘The Three Crowns of King Arthur’, in the Yorkshire Archaeological Journal Vol. 38.

Smith, A. H., 1961, Place Names of the West Riding of Yorkshire

Smith, A. H. 1967, Place Names of Westmorland.

Westwood, Jennifer, 1987, Albion, a Guide to Legendary Britain

Published in NE91, Autumn 2002, p9-12