Robert W E Farrah suggests an archaeo-astronomical interpretation of a carving on a lintel-stone at the Parish Church Of St Margaret And St James, Long Marton, Cumbria.

Long Marton is a fell side village in the Eden Valley below the Pennine fells on the E side of the R Eden, some 5km (3.11m) N of Appleby, the old county town of Westmorland. The village’s ancient name is Mereton, ‘homestead (ton) by the mere’. The mere can still be seen after prolonged rain, when the water meadows flood alongside Troutbeck, which flows through the village between Marton Hall and the Church to the Eden.

The church is dedicated to St Margaret and St James. The earliest part, comprising the nave and half the chancel, dates from c1100 CE. The nave and W half of the chancel, with all its original wall, may give Long Marton the distinction of being the second oldest in Cumbria (Winterburn, 1983:17). There are signs of Saxon workmanship in the church, although it was probably built under Norman supervision. It has been suggested that a wooden church existed before the present one, indicated by the extreme irregularity of the existing fabric (Cory, 1880). The Church is located upon an elevated terrace above the valley of Trout Beck, about ½km (0.31m) S of the present village.

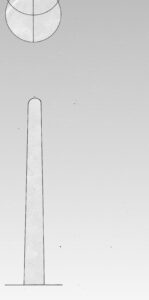

The church has several features of interest, the best two documented being the two tympana, one over the S entrance and the other over the original W doorway; both are probably Saxon. But it is the incised carving on the lintel over the S window of the chancel which is of interest here and which I suggest is of particular importance to archaeo-astronomy (Figs 1 & 2). A mysterious ‘high authority’ has suggested that this carving depicts an astronomical event related to a standing stone; if so, then it constitutes the earliest known record of a celestial event at a megalithic monument, pre-dating William Stukeley’s earliest documented observation of the midsummer sunrise above the Heel Stone at Stonehenge “where the sun rises, or nearly at the summer solstice”. This article presents evidence in favour of an astronomical interpretation of the carving and to support and substantiate the claims of the ‘high authority’ (See below). If this is so, then the lintel carving is evidence of an awareness of megalithic astronomy continuing into historical times – a unique record from antiquity in its depiction of a solar/lunar rise or setting in conjunction with a megalithic monument.

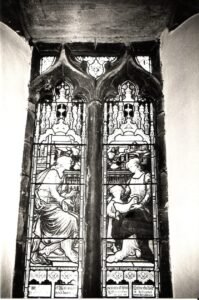

Winterburn’s description of the lintel, published in a parish booklet, is the only one extant:‘The lintel stone in the S wall of the chancel is carved with an obelisk rising from the ground, represented by a straight line towards a double circle. It has been suggested that it symbolises sun-worship and the fertility of the soil, and that it is Phoenician in origin. It seems likely that it came from the nearby Roman fort Bravoniacum (Kirkby Thore). The area of Burwen Hill has produced many Roman finds since the 17th century’ (Winterburn, 1983:25). The lintel of red sandstone is above a double light of stained glass, which has a dedication to Ann Heelis, wife of Rev. Edward Heelis MA, rector of the Church 1833-1874. The window was erected by their 20 grandchildren in 1886. The double circle is incomplete, due to the lintel being recessed into the wall. The appearance of circularity is also evident in a closer inspection of the double circle’s measurements. It was ascertained that the diameter of the almost complete circle varies from 200.2-206.17mm. The variance of 12.7mm can be accounted for by the groove made by the cut of the tool used in the carving, which varies from 3.17-9.52mm. The accuracy suggests the use of either a template or compass prior to execution. What remains of the upper circle is enough to show that this circle must have been larger than the lower one, measuring 209.35mm where it meets the wall. The vertical axis of the lower circle (which is also that of the upper circle) directly above the menhir-like depiction is 9.52-12.7mm off-centre. The carving seems to suggest a sun or moon rising or setting above a standing stone (Fig 3).

Fig 1. South Window of the Chancel (photo Peter Koronka)

Prof Richard Bailey, co-editor of the Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture’does not agree with the Winterburn description, though he does not recall seeing this particular sculpture when visiting the church. His own view is that the sculpture is a “fragment of a late 12-13th-century grave-cover, recycled into the fabric of the building, probably in the course of the 19th-century restoration. Such grave-covers are decorated with swords, shears, long-stemmed crosses with floriate heads and various geometric shapes” (pers. comm.). He suggests that the lintel fits into this pattern and that the obelisk identified is probably the blade and point of a sword. There is such a decorated grave-cover in the floor of the porch entrance, but it differs from the incised carving of the lintel, having been executed in relief. Bailey also believes that “no reputable ’high authority’ would seriously suggest that sun-worship, soil fertility, still less Phoenicians could be invoked in explanation of this stone” (pers.comm.).

Fig 2. Lintel Stone in South Wall of Chancel (photo Peter Koronka)

Fig 2. Lintel Stone in South Wall of Chancel (photo Peter Koronka)

There is no mention of the lintel in any of the major reference works on local antiquities, though the two tympana are frequently mentioned. This could be because the lintel was not there prior to the major restoration. The restoration plans were drawn up by John A. Cory, a Carlisle architect who provided a complete internal restructuring. The chancel and windows are known to have been a part of this restoration. Permission for this work was granted on 17th March 1880 and it was completed by 21st July, when the Lord Bishop of Carlisle officiated at a celebration service (Winterburn, 1983:20-24). References post-restoration also fail to mention the lintel, perhaps due to duplication of previously published works. Two articles written at the time of the restoration also fail to mention it; the first by the architect himself (Cory. 1880), while the second, by the Rev. Thomas Lees, deals specifically with the two tympana (Lees, 1881).The reason could also be that instead of the sculpture being perceived as unique, as Winterburn suggests, it has been seen, as Bailey suggests, as an unfinished carving deemed unworthy of serious study when finer examples exist elsewhere.

Besides the lintel being mentioned more recently, from notes prepared by this author (Robertson & Koronka, 1992:83), there are only two other known references to the carving; these are held in the County archives at the Cumbria Record Office, Kendal. These are the field notes for the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments which has a sketch of the stone, with no accompanying description or explanation. The Commission’s published volume on Westmorland (1936) does not mention the stone. The other source is a board on which is attached ‘Notes on Long Marton Church’, which presumably used to hang inside the church. It is now in the office together with the parish records (ref: WPR/44/Z14). The authorship and origin of these notes is unknown. They may be from a newspaper cutting; they are undated but must have been written after 1905 which appears in the text. It would seem that these notes are the immediate source of information quoted by Winterburn, although there is a slight difference in description; “The lintel of a window on the S side of the Chancel is carved with an obelisk rising from the ground, represented by a straight line, towards a double circle. Its meaning is a puzzle. A high authority has suggested that it symbolises sun-worship and the fertility of the soil, and is of Phoenician origin. If this is so it may have been brought to its present position from the remains of a Roman camp which once existed in the neighbourhood”. The Roman camp is almost certainly the Roman fort of Bravoniacum at Kirkby Thore, which Winterburn correctly identifies. The intriguing addition to Winterburn is the detail that attributes the interpretation of the lintel carving to ‘a high authority’.

Winterburn’s acknowledged source was the late Martin Holmes, ex-Mayor of Appleby and once private secretary to Sir Mortimer Wheeler, a position he left to become Assistant Keeper of the British Museum. Holmes was a choirboy at Long Marton and remembers Canon Robert William Harris explaining the detail on the lintel to him (pers.comm.). John Harris, the sole surviving son of Canon Harris, remembers his father as the origin of the Winterburn description, but believes he held no great belief in its authenticity. He doubts that his father could have been the true source, as he would have had more faith in its correctness (pers. comm.).

In the absence of any positive documentation it is difficult to ascertain exactly when the lintel was inserted into the window or its provenance. There is mention for instance that “In the secluded churchyard, where “the rude forefathers of the parish sleep”, are many neat monuments, some of which are of considerable antiquity” (Mannex and Co. 1851:174). The possibility that the stone came from Bravoniacum seems to be based on the assumption that the stone is of Phoenician origin, as mentioned in the ‘Notes’. This fort was originally founded by Julius Agricola during his early campaign of 79-80 CE and was rebuilt in stone early in the 2nd century. A unit of Syrian archers are thought to have served here in the 3rd century, as indicated by an inscription on an altar stone bearing the letters ‘N.M.S.S.’, which is thought to translate as ‘a military unit of mounted archers from Syria’ (Southworth, 1985: 176).This has historical plausibility, as it is known that many finds from this fort were dispersed (Ferguson, 1894: 44-45); stone recycling was a common Norman practice.

If the lintel does originate from from Bravoniacum, then there are two other possibilities for its presence at Long Marton. The first is Thomas Machell, a Rector of St Michael’s at Kirkby Thore (1677-1698). Machell has been described as the father of all Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquaries. During his incumbency, more of the external remains of the fort were visible and he carried out extensive excavations (Rogan, 1956:143-44). Not only an archaeologist, he was also a conscientious parish priest and an architect credited with several local commissions, such as the Organ Loft at St Laurence’s, Appleby (Rogan, 1956:139). He is known to have had an interest in the parish of Long Marton, for he bequeathed the sum of £20 for the encouragement of a singing master to teach psalmody at the church (Whellan, 1860:756). If the lintel was incorporated when the Ann Heelis window was installed, then it is possible that John Heelis, who was also Rector of St Michael’s, was the principal protagonist. His rectorship (1880-1893) coincided with the installation of the Heelis window in 1886. John was the son of Edward Heelis, vicar of Long Marton (1833-1874) and Ann, to whom the window is dedicated. The Rev. John Heelis and his wife Esther had 11 children, who all contributed towards the window dedicated to their grandmother. While rector, John Heelis wrote a paper on St Michael’s and significantly mentions that “In examining the masonry of the church, one naturally looks for stone bearing the marks of Roman tooling or other indications of having once formed parts of Roman edifices in the neighbouring fortified garrison town of that people” (Heelis,1891:322).

The want of light from the small Norman windows resulted in the remodelling of the chancel and the introduction of larger windows. The windows in the S chancel date from c1350. John Cory’s Plans and Elevations of the Church “shewing proposed repairs in the part coloured”, indicate that only the stonework of the windows on the N side of the chancel were subject to restoration (Cumbria Record Office. Kendal. Ref; WPR/44/144). The Faculty of 3rd April 1880 issued for the restoration gives licence “to replace Tracery in such windows as have been deprived of it and reglaze the same” (Cumbria Record Office. Kendal. Ref; WPR/44/147). Some of the stone of the chancel window lintels does have a cleaner, fresher appearance than the respective stone of the windows, suggesting a more recent restoration.

This about exhausts investigation into the sources and possible provenance of the lintel.

Archaeo-astronomical interpretation

The only interpretation of the lintel other than Bailey’s is that of the ‘high authority’. We need to ask why that ‘authority’ related it to sun-worship and fertility and whether this makes sense with what is known concerning megalithic astronomy – does the carving depict a unique event familiar to megalithic astronomy?

The only interpretation of the lintel other than Bailey’s is that of the ‘high authority’. We need to ask why that ‘authority’ related it to sun-worship and fertility and whether this makes sense with what is known concerning megalithic astronomy – does the carving depict a unique event familiar to megalithic astronomy?

The double circle immediately above the ‘obelisk’ is the only feature reminiscent of a celestial body on the carving which gives substance to our ‘high authority’s’ suggestion of sun-worship. A single circle would have been a more rational representation, unless the motive of the double circle was to suggest movement. If the circles are interpreted as celestial, then such movement can only mean a rising or setting. In this context it is interesting to note that the top incomplete circle has been carved larger. The vertical line bisecting both circles seems to align central to the obelisk, a feature unnecessary to the carving of the circles. But if we interpret the circles as celestial, it could serve to emphasise the circles’ alignment with the obelisk. If this interpretation is correct, then the carving could be seen to represents the rising/setting of the sun/moon in alignment with a standing stone, a familiar phenomenon in archaeoastronomy.

The High Authority

It is unlikely that the identity of the ‘high authority’ will ever be definitively known, but the description of the lintel carving as symbolising ‘sun-worship and the fertility of the soil and is of Phoenician origin’ suggests certain affinities with George Watson. A subtitle on the cover of his publication concerning the astronomy of the ‘Long Meg Druidical Circle’ refers to the monument’s ‘Adaptation to Sun-Worship’ (Watson, 1900). The ‘Notes on Long Marton Church’ held in the County archives at the Cumbria Record Office in Kendal also date to soon after Watson’s publication. It is likely that Watson’s combined interest in church orientation and prehistoric astronomy would both enable and qualify him to be described as a ‘high authority’, able to understand the meaning and significance of the lintel stone. It is clear from his ‘Prefatory Note’ to his paper on ‘The Orientation and Dedications of Ancient Churches in England and Wales’ (Watson, 1898), that Watson was a resident of Penrith. Besides looking at church orientation on a national level, approximately half of this paper considers churches local to the diocese of Carlisle. In ‘Table 2 – Orientation of Churches in the Diocese of Carlisle’ he lists many fell-side parish churches, including St. Margaret and St James at Long Marton (Watson,1898.6). It is likely that Watson visited the church during his research into church orientation and saw the lintel stone, which he interpreted according to his research at Long Meg and Her Daughters. The latter was published in 1900, two years after the church orientation work; Canon Harris‘s incumbency at Long Marton commenced in 1903. Presumably Canon Harris’s knowledge and interpretation of the lintel carving was either taken from the ‘Notes’ which might have hung in the church during his incumbency, or was received more personally from the previous Rector, Frederick St. John Corbett, whose incumbency (1896-1903) coincided with both the Watson publications. If one megalithic stone was to be chosen as a depiction of the carved ‘obelisk rising from the ground’ then it would surely be the tall slim outlier of Long Meg, which “rising…towards a double circle”, Watson would have recognised as reminiscent of the winter solstice sunset at that monument.

References

TCWAAS= Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Archaeological & Antiquarian Society

Cory, John A. 1881. ‘A Historical Account of Long Marton Church, as shown by its Masonry’, TCWAAS Old Series, Vol. V.

Farrah, R.W.E. 2001. ‘Mayburgh henge : A Sacred Space Odyssey’. Northern Earth 85.

Farrah, R.W.E. 2006a. ‘Castlerigg – By the light of the Silvery Moon’. Northern Earth 105.

Farrah, R.W.E. 2006b. ‘In Ancient Moonlight’. Northern Earth 106.

Farrah, R.W.E. 2008. A Guide to the Stone Circles of Cumbria. Hayloft.

Ferguson, Richard S. 1894. A History of Westmorland. London.

Heelis, Rev. John. 1891. ‘Kirkby Thore Church’, TCWAAS Vol. XI.

Hood, S and Wilson, D. 2002. ‘Long Meg Midwinter shadow path’, TCWAAS 3rd Series, Vol. II.

Hood, S and Wilson, D. 2003. ‘Further Investigations into the astronomical alignments at Cumbrian prehistoric sites’, TCWAAS 3rd Series, Vol. III.

Hood, S. 2004. ‘Cumbrian stone circles, the calendar and the issue of the Druids’, TCWAAS 3rd Series, Vol. IV.

Lees, Rev. Thomas. 1881. ‘An attempt to explain the sculptures over the South and West Doors of Long Marton Church’, TCWAAS Old Series, Vol. V.

Robertson, D & Koronka P. 1992. Secrets and Legends of Old Westmorland. Pagan Press/ Cumbria County Council Library Services.

Rogan, Rev. John & Birley, Eric. 1956. ‘Thomas Machell, the Antiquary’, TCWAAS, New Series, Vol. LV.

Southworth, James. 1985. Walking the Roman Roads of Cumbria. Robert Hale.

Watson, George. 1898. The Orientation and Dedications of Ancient Churches in England and Wales. R. Scott, ‘Observer’ Office, Penrith.

Watson, George. 1900. ‘The Long Meg Druidical Circle near Penrith, Cumberland: a suggested theory of its geometrical construction, and adaption to sun-worship. Penrith.

Whellan, William. 1860. The History and Topography of Cumberland and Westmorland. Pontefract, London and Manchester.

Winterburn, G.H. 1983. ‘Long Marton – A History of a Cumbrian Fellside Parish and its Early Norman Church’. Priv.

Published in NE126 (Summer 2011), pp.16-21