By John E. Palmer, 2024

Springendal is a protected nature reserve near Hezingen, in the province of Twente in the Netherlands. In April 2019 two metal detectorists (1) searched on terrain belonging to Staatsbosbeheer(Forestry Commission) and found some gold coins which they were unable to interpret or date. After consultation they decided to duly report their finds to the authorities.

The Free University of Amsterdam initiated an excavation, achieved by archaeologists with the Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed (State Agency for Cultural Heritage) on the site of discovery which is situated on a high moraine, but this needed to be postponed due to the Covid-19 pandemic. During the autumn of 2020 and 2021 several detection surveys were conducted by ten archaeologists and 5,400 square metres of soil was examined and every feature documented. Flint artefacts, some burnt, which may be associated with transformation by fire and ritual deposition, from the Neolithic Funnelbeaker culture (about 4300–2800 BCE) and late Mesolithic came to light.

Interestingly, four straight rows of post holes were recorded, these were oriented east–west and aligned to a large granite glacial erratic situated at the east. At the post holes were discovered gold and silver coins and more gold was found deposited at a stone (2) (most of the coins are tremisses and sceattas – one coin is a pierced Roman denarius). The stone was buried, probably in the middle of the 19th century.(3) It resurfaced during the excavation, and it still remains at its original site.

The stone appears to have been sited at a an ancient crossroads or tracks; these disappeared tracks are marked on a map of 1830 and are thought to hark back to the early medieval Merovingian period. In the vicinity are several round barrows. To the Germani, crossroads held a deeper significance and were believed to be places where spirits meet and hence such were deemed to be appropriate places for divination.

The granite stone, focus of the Saxon alignment. Photographed on film by the author, July 2023.

The entire alignment of post holes was 30 metres long (98,4252 feet); the four segments are offering sites presumed to have been set out in periods of ten years. This pagan Saxon sanctuary or ‘fanum’ was established in the sixth century CE and was used into the seventh.

In Britain a votive altar stone from Housesteads, removed from Hadrian’s Wall, is inscribed with a text which mentions Thingsus (god of the Thing, of justice) and the serving cavalry of the Germanic Tuihanti. These are the Tubanten, and it is assumed they came from the region of Twente.

Missionaries including Liudger knew about the pagan Saxon tradition of offering gold at places of their devotion; it is recorded that in the year 784 Liudger went to Friesland where he destroyed and robbed Saxon sacred sites, and he returned with a cart laden with gold. The missionaries never proceeded beyond conquered lands and were protected by the Frankish army. The Saxons resisted conversion and under their ‘duke’ (leader) they fought the army of Charlemagne. At Verden he ordered the beheading of 2,000 Saxons daily, and duke Widukind implored him to stop killing his people, saying he would accept the new religion.

In a news message issued in February 2022 by the State Agency for Cultural Heritage and published in every newspaper and archaeological journal in the Netherlands concerning the excavation at Springendal, there were references to ‘a row of posts, possibly affixed with holy signs or a Woden’s head ’.(6) The latter assumption appears to have been derived from an old Saxon baptismal promise, (7) by which the converted disavows the deities Woden, Donar and Saxnot.

Being aware that a finding a Woden’s head would be extremely rare indeed, I contacted the State Agency. I was put in touch with Mr de Kort; he conducted the excavation at Springendal. He said the Woden’s head was an invention by his colleagues. I asked what exactly was found then. He replied there stood a row of 17 post holes. The orientation was about east–west of this row of post holes. At the eastern end of the row of posts is a large erratic stone, buried in a ‘recent’ pit. Jewellery was deposited around this stone. The coins were found north of the row of posts or against the posts or in the post holes.

I pointed out the east–west orientation sits straight on the Equinox. Surprised, he exclaimed: ‘What?!’

Articles published after completion of the excavation, written by J.W. de Kort and professor B. Groenewoudt,(4)(5) make no mention of an alignment to the equinox. None of the numerous official bodies involved with the results of the excavation make reference to it either.

I pointed out to Mr de Kort that according to the De Temporum Ratione, written in England by the Venerable Bede (673–735) the Anglo-Saxons brought sacrifices to the goddess Hreda (Old English Hreda, glory or fame) and Eostre, equating Hredmonath with March and Easturmonath with April; Eostre is goddess of the east, of the dawn, and she gave her name to Easter.(8) This date is calculated according to the first full moon after the spring equinox. The associated rites would be concerned with celebration of spring. This might have involved flowers and dancing on May Day, adding the feast which became assimilated into Christian Easter, and Easter fires were lighted on hills during spring festivals, which occurred in the territory of the northerly Germanic peoples.(9) Both Hreta and Eostre appear to be aspects of Mother Nature in her young and vernal dress.(10)

Along with the gold and silver coins, the excavation at Springendal revealed fragments of gold jewellery, a possible indication that women took part in depositing offerings at the alignment to the goddess of dawn.

Plan of the alignment excavated at Springendal. The black dot (S120) marks the stone. Reproduced from Goud voor de goden. 2023. State Agency for Cultural Heritage.

While Mr de Kort appreciated the astronomical information, he expressed his surprise at the backlash of emotional reactions these sorts findings generate in professional archaeological circles, as also from wider society, both in a positive and negative sense.

It is likely the offerings at Springendal were conducted at the spring equinox. At that time the sun rises exact in the east and sets exactly in the west, and the daylight is of the same duration as the night. At the equinox the shadows of a vertical standing post at sunrise and sunset form a straight line. In illustrating the concept of the gnomon, the late Keith Critchlow used a photograph depicting two indigenous Borneo tribesmen measuring with a stick the shadow of a post to establish the length of the midday shadow over the year.(11)

‘Orientation gives direction and is the vital factor in ensuring the effectiveness of a holy place,’ wrote Critchlow.

The equinox was a key date in Christian theology and while the equinoctial orientation can be found in some early churches, this was not to last; it became irrelevant and it was finally disregarded.

During the excavation Mr de Kort found some more post holes beyond the aligned east–west rows; however, these other holes had been ‘shaved short’ apparently during recent agrarian activities. He began to draw short several parallel lines with an angle of 47 degrees in which he saw an ‘observatory’, with which I disagreed; he assumed these lines indicated midsummer sunrise – I corrected this to summer solstice sunset. I think it is unlikely these medieval people constructed an astronomical observatory.

One requires both foresight and backsight to set out intentional alignments such as are found associated with the agrarian cycle fused with the cosmology which engendered the construction of prehistoric monuments. I remarked that the human inclination for the straight is universal, and that we could be witnessing one of the very last alignments; the knowledge derives from very ancient traditions, harking back to the Neolithic and Mesolithic, and in the Low Countries symbolic solar alignment exists in the layout of post holes encircling round barrows.

The literature catalogue in Goud voor de goden lists two of my publications in England.(12)(13) De Kort asked for a copy of my book, The Blue Stones: An Investigation of Judicial Stones in the European Middle Ages.(14) I then donated a copy of the book to the library of the State Agency for Cultural Heritage; he remarked the book has ‘no publisher’ (sic) and I heard no more about it. Usually when a library accepts a donation, notice of this will be duly sent to the donator and some libraries register the donation in their annual report.

Only later De Kort said that he found my book interesting and all the time he had it on his bureau. When I read Goud voor de goden, I found de Kort had introduced in its pages specific judicial terminology which only now became prominent in Dutch archaeology, including Thing/Ding place, assembly place, maalstede and other toponyms associated with judicial proceedings; many such places were associated with ancient monuments and specific stones. De Kort was convinced – ‘toponyms indicating an assembly or judicial site should be taken into consideration’ – but he opted to mask the source of this insight.

That Ding/Thing sites were surrounded by a vibond (holy bond) he borrowed perhaps from my book, although this circular character of a vibond is irrelevant to the linearity of the Saxon alignment under discussion. De Kort omitted to state that demarcation specifically by hazelrods and the vibond was used at northern Thing sites and in Greece.

De Kort appeared to have amused himself by recording my information concerning the equinoctial alignment into micro lettering, and finding on his computer other sources of reference for the judicial themes throughout in a bid to avoid listing my book. No explanation was forthcoming, and as old Plato expressed it, ‘silence implies consent’.(15)

I am critical of erasing all traces of monuments in excavation; de Kort told me ‘archaeology is destructive’, while I believe the consolidation of the outlines of excavated important monuments could save for posterity much of our rapidly disappearing ancient cultural heritage, which would be responsible in view of the State Agency for Cultural Heritage he is working for. Only saving barrows in protected nature reserves is not enough, and reflections concerning numinosity when excavating human remains ought to be taken more seriously.

The Saxon offering site in Springendal is a beautiful place, there is a sea of yellow tansy with dark wood at the horizon. At the nearby footpath the Forest Commission erected three large three trunks; the middle one is carved with a Woden’s head by chainsaw artist and forester Albert Broekman. Curiously, the three trunks are not oriented towards the east–west alignment but sit at right angles to it. The original Saxon alignment will not be reinstated as the Forestry Commission is ‘rewilding’ the area and refuses permission.

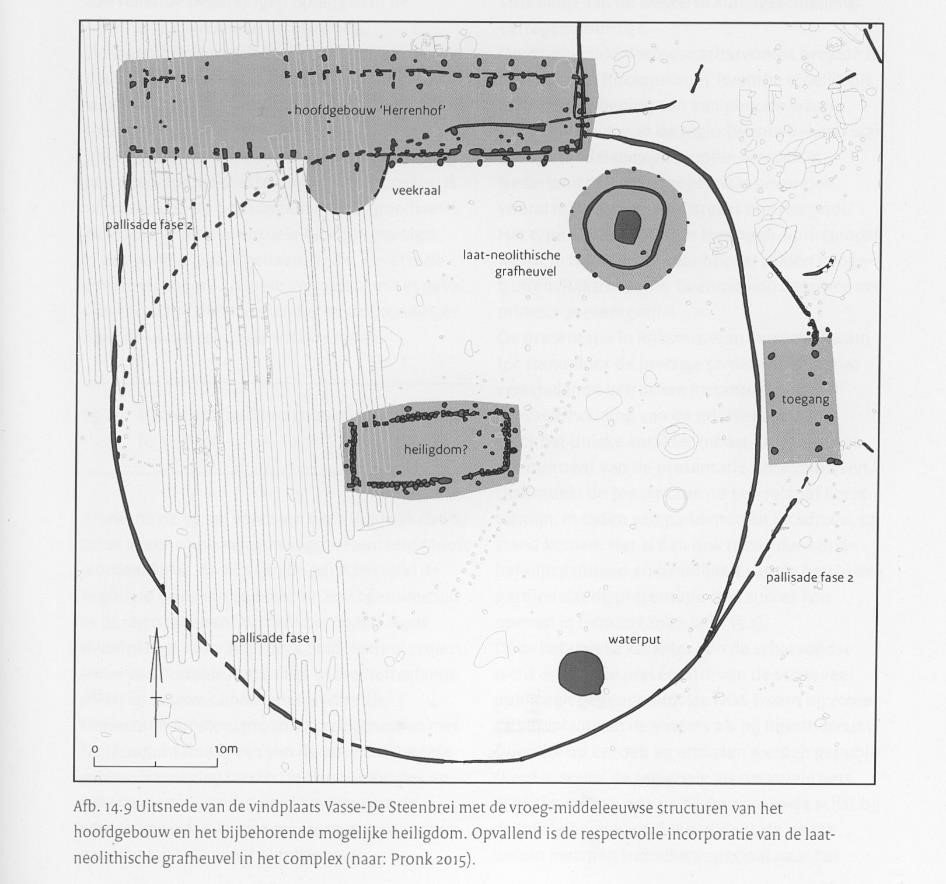

The Saxon nobility which brought offerings at Springendal may have had their residence in the vicinity; several sites of medieval ‘borgen’ (defendable farms) are known near Hezingen. (16) Some 3 km away from Springendal, at Vasse Steenbrei, the post holes of an early medieval ‘herrenhof’(a hof means both garden and court, judicial court) were excavated,(17) which was enclosed by a semicircular stockade, and to the north was a residential quarter with a kraal for cattle. In the middle of the stockade was a rectangular hall or temple or communal building. At the north-east was a round barrow encircled by 14 posts, which might have played a role when justice was spoken. Vasse is situated at lat. 52° 25’ 59.99”. From the centre of the hall could be observed the midsummer sunrise over the barrow; this does not make it an observatory, though it may be a symbolic orientation. The excavators failed to notice that the central orientation of the hall was east–west, symbolically aligning with the gate to the east, where the sun rises.

Excavation groundplan by Pronk (2015) of the early medieval Saxon hof at Vasse Steenbrei. Reproduced from Goud voor de goden, State Agency for Cultural Heritage.

There is however a few degrees difference with the east–west orientation, as if the draughtsman was not acutely aware of the difference between wavering magnetic north and geographic north, as was formerly not uncommon among Dutch state archaeologists. The obvious accuracy of the east–west alignment of the Saxon offering site at Springendal is of striking equilibrium.

Notes and comments

(1) The metal detectorists are Martin van der Beek and Gerben ten Buuren. Archaeologists with the State Agency for Cultural Heritage view them as ‘hobby archaeologists’.

(2) Goud voor de goden (Gold for the gods), Investigation of a cult site from the early middle ages in the nature reserve Springendal near Hezingen (municipality of Tubbergen), with large folded maps to scale, by J.W. de Kort, B. Groenewoudt and S. Heeren (et al – 20 authors are listed). Published in the Dutch language by the Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed, Ministerie van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap. (State Agency for Cultural Heritage. Ministry of Education, Culture and Science). Amersfoort, 2023.

(3) De Kort, (personal comment) repeated in Goud voor de goden.

(4) O Wodan aanvaard mijn offer. (‘O Woden, accept my offering’), article by J.W. de Kort, field archaeologist at the State Agency for Cultural Heritage, and professor Bert Groenewoudt, landscape archaeologist at the same Agency, and Stijn Heeren, lecturer at the Free University of Amsterdam. This article appeared in February 2022 in various publications.

(5) Offers aan de goden? (‘Offerings to the gods?’) article by professor Bert Groenewoudt, published in Archeologie in Nederland, Jaargang 6, Deel 1, March 2022.

(6) The original text in Dutch runs: ‘Daarbij werd nog meer goud en zilver gevonden, en sporen die behoren bij een offerplaats. Een aantal palen op een rij, mogelijk voorzien van heilige tekens of een Wodanskop, vormden waarschijnlijk een ontmoetingsplek, waar groepen mensen uit omliggende gebieden elkaar ontmoetten, en daarbij edelmetaal achter lieten.’ Nieuwsbericht (News message) from the Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed, 16-02-2022.

Mr de Kort subsequently commented this was made up by their department of communication, and that the word ‘mogelijk’ (= possible) had disappeared from many newspaper reports. He thought it to be tendentious and amounts to the sensational. He added wryly ‘there are just not yet offerings of innocent children’.

(7) This vow is found in the Codex Palatinus Latinus 577.

(8) Rites and Religions of the Anglo-Saxons, by Gale R. Owen, Dorset Press 1985. While I pointed out this scholarly work by a lecturer in the English Department of Manchester University, this was ignored by the authors of Goud voor de goden.

(9) Teutonic Mythology II by Grimm. The German word Ostern is related to east, thereby Grimm suggested the spring goddess Ostara.

(10) The Lost Gods of England, by Brian Branston, Thames and Hudson Ltd, London, edition 1974. Branston spells the name of the goddess as Hreta.

(11) The photograph is in his book Time Stands Still: New Light on Megalithic Science, published by Gordon Fraser, London 1979.

(12) ‘Ancient Solar Symbolism in the Netherlands’. Northern Earth, issue 76, 1998.

(13) ‘Solar/lunar symbolism on the Rechte Heide (heath), Netherlands’. Time & Mind: the Journal of Archaeology, Consciousness and Culture. 2017.

(14) The Blue Stones. (2019. Hardbound, 369 pages) In my view it is the only comprehensive book about judicial stones and the custumals associated with these stones. I researched the matter of judicial stones for 45 years. I issued it myself in a small edition and I donated copies to national and research libraries. In the UK, the Society of Antiquaries London, the principal research source for archaeologists, and the National Library of Wales, at Aberystwyth, have accepted a copy of my book. It was read by Richard Harrison, a professor of anthropology and archaeology, who opined: ‘it’s an unusual subject, and a large collection of empirical data, covering many different fields and historical enquiry’ (personal communication).

Mr Peter van Beest, co-ordinator of Donations at the Royal Library Den Haag commented : ‘I did not know the idea of the judicial stone and I found no publication about it in any library in the Netherlands’ (personal communication).

(15) In Plato’s dialogue Cratylus, the wording spoken by Socrates is: ‘for I take it that your silence gives content’.

(16) De borg te Hezingen. by H. Woolderink, in: ‘t Inschrien, Vereniging Oudheidkamer Twente, Jaargang 28, nr 1, 1996.

*** * ***