Many stones around Britain bear the name ‘pennystone’, and have often been explained as plague stones. John Billingsley (with a little help from Robin Hood) cures these stones of their ague

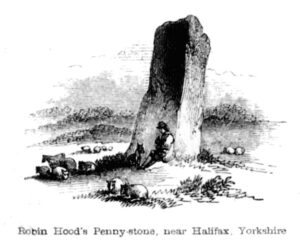

Near Halifax in W Yorkshire, on Midgley Moor, and at one time on a hillside at Wainstalls, you could find large boulders called Robin Hood’s Pennystone; both were said to have been tossed over the Calder valley from Sowerby by Robin Hood1.

Robin Hood’s Pennystone, Midgley Moor

Possible depiction of the Warley Robin Hood’s Pennystone from the 18th century.

A little to the N of these, on the edge of Haworth and overlooking the village, is Penistone Hill. Perhaps it once had a boulder on it, maybe 4 or 5ft across, like the Pennystone in Kirkmabreck in Galloway, Scotland, under which, it was said, some treasure was likely to be found.

Over near Blackpool, at Singleton Thorpe, a Penny Stone was to be found outside the door of the Penny Stone Inn; it was said to be the sole remnant of a Druidical stone circle2. There was an iron ring in the Singleton Thorpe boulder, to which customers could tether their horses3.

There are, or were, many other pennystones to be found in the North of England and Scotland, and a diligent search of place-name records, looking at a small range of variant spellings, will reveal them.

What are these Penistones? Some are spelt Penny-Stone, the penny with the stone; others are spelt in a way, Penis-stone, inviting a more salacious interpretation by those people with too much Freud on their minds, too literal an imagination or an obsession with associating things that are taller than they are wide with the phallus. I am tempted to say that I think we needn’t bother with this interpretation – but I wouldn’t bet against there being a phallic folk-tale locally told about some Penis-stone, somewhere.

I used to think – thanks to Jessica Lofthouse – that these penny stones were remnants of trading sites.

Plague stones: left, Kirkstall Abbey Museum. Leeds. Right: Ackworth, W. Yorkshire

The Plague Stone at Eyam, Derbyshire, where the plague claimed 260 lives in 1665-66

The idea was that when plague afflicted a village, traders would not come into the infected town, but stop on the outskirts at a designated place, usually a stone with a convenient basin in its crown. This basin would be filled with vinegar, and transactions made at a safe distance – no shaking hands on this deal – and then any money changing hands was deposited in the vinegar as a disinfectant. Not much use if the plague was coming in from outside in the form of fleas nestling inside bales of wool, as is supposed to be how the plague came to Eyam in Derbyshire, but it was better than nothing. Such stones could also be called Plague Stones, understandably. There’s one at Giggleswick, N Yorkshire, helpfully explained by an inscription, ‘Plague 1666’. Halton on Lune and Brookhouse near Caton, in Lancashire, have such stones, too. A number, like the Giggleswick Plague Stone, were cross bases – the basin is the hole for the vanished cross shaft, which naturally implies the tradition postdates the Protestant iconoclasm of the 16th and 17th centuries, and of course crosses would often stand at village boundaries3a. At Mitton Green such a cross base is known as the Vinegar Well in an obvious allusion to this custom. But when Lofthouse blithely declares “Penny Stones, Plague Stones: synonymous”, is she right, or is she being, shall we say, a little enthusiastic, careless, perhaps? 4

Well, there may indeed be some overlap. In S Yorkshire, on the banks of the River Don, is a town called Penistone. There’s no record of a penny stone there as such now, but in 1273 a market charter was awarded to a lost manor of Penisale5 – though this sounds like a mediaeval predecessor of Poundland, could this market charter have grown up around an informal market? That is pure speculation on my part, and I really do not know.

But Lofthouse is not the only one to merge plague stones and penny stones so easily, and I suspect in the 19th and early 20th centuries this may have been a common supposition.

Coins in basin atop the Midgley Pennystone

Coins in basin atop the Midgley Pennystone

An existing custom at Churn Milk Joan on Midgley Moor – of taking any money you find atop the stone and replacing it with an equal or greater amount from your own pocket to assure you of good fortune – is clearly in inspiration a trading custom, similar to the plague practice, though here imported inappropriately to a standing stone over 6ft tall. I used to assume, like others before me, that this must be a plague stone custom, migrated around the moor from Robin Hood’s Pennystone – similarly inappropriate as a plague stone, however, because of its location and distance from township and trackways; but now I believe that the Pennystone name and the Plague Stone custom, in their popular association, were more likely the joint inspiration for some person unknown who concocted the Churn Milk Joan ritual, i.e. the custom was probably a moralising diversion for children brought up to the moor by their parents, as the moor was locally considered to be health-giving for ailing children. The moral of the custom was ‘as long as you give as good as you get in exchange, you’ll be assured of respect and good standing’ — a good thing to teach your kids.

Churn Milk Joan

Churn Milk Joan

Indeed, I think it’s perfectly safe for us to ditch entirely the allegation of Plague Stones and Penny Stones being synonymous, because there is quite simply a much easier and more reasonable explanation.

In 1539, citizens of Halifax made complaint that there were locally “contrary to the King’s Acts, certain that doth play at the pennistone, the which is an unlawful game, and pulls down men’s walls and breaks their stones”6. This one 16th-century allusion spills the beans – pennistone was a game, played with stones. Jeremy Harte alerted me to the word pennystane in Scots dialect, meaning ‘a round flat stone used as a quoit’, and it also appears in Geordie dialect; Sir Walter Scott used a ‘pennystone-cast’ as a measure of distance in Guy Mannering and Heart of Midlothian. At South Leith Kirk Sessions in 1610, the spoilsports forbade ‘public playing… on the Sabbath days, such as playing at bowls, at the penny stone, archery, golf’7.

But how was it played? It was a member of the quoits family, but much more informal. Quoits is an ancient game, thought to be related to discus throwing, but with the additional feature that the missile is thrown at a mark. True quoits is played with an iron disc, or ring – the former, with a disc, is a measure of straight-and-true accuracy, as it is thrown to hit the mark; the latter, with the ring, is a more subtle kind of throw, as it should not just reach the mark, but settle itself upon and around it.

It could be dangerous – in 1409 a 9-year-old girl at Laverstock, near Salisbury, sitting 12ft beyond a mark set up for a game, was struck by a 1lb iron quoit thrown too hard by a local carpenter; it cut through her scalp and exposed her brain, and she was out cold for an hour and a half – long enough for the carpenter to run to Salisbury Cathedral and claim sanctuary there and pray for the child’s life. She did in fact recover, which did no harm at all to the priests’ insistence that prayer works8.

It wasn’t just health and safety that made Edward III and Richard II proscribe quoits in favour of archery, though – it was because quoits was thought to be a bit, well, common; as Strutt says, writing around the turn of the 19th century, “It seems always to have been, as at present, a game chiefly popular among the working classes, although it admits of much dexterity, skill and judgement”. He describes the game – briefly, here – as two iron pins being driven into the ground a certain distance apart; the contestants stand at one and cast their quoits at the other, reckon up the tally of hits or near misses, then do it the other way, and so on until a result is reached. Gambling would undoubtedly have been involved – the winner would have won something to make it worth the time and effort.

If there were no iron quoits to hand, then horseshoes were a very good alternative; and if there were no horseshoes to hand, well, depending on where you lived, there might just be stones, and here we recall the Halifax complaint of the unlawful game that pulls down men’s walls and breaks their stones. Now Henry VIII was, unlike his predecessors, not so much concerned about how couth or otherwise it was, nor about the gambling taking place amongst the poorer classes, but about the vandalism that some of his subjects were getting up to – in his Witchcraft Statute of 1542, for instance, seeking out buried treasure was forbidden, because such activities had “dygged up and pulled downe an infinite nombre of Crosses within this Realme”. Such monumental concern was of course not always displayed towards religious houses, however, in his reign.

So what we learn from all this is that if you were playing a kind of quoits that involved throwing stones at a mark, and you were playing for money, then you were probably playing pennystone – an informal and inexpensive version of the game for which the material lay plenty to hand all around, and that you could set up at a moment’s notice. As Strutt says, quite likely to be popular amongst working men.

But if you were in an area without ready stone, and you had no iron to hand, either, what were you to do? A related game is penny-prick, common in the 15th century at least – “The game consisted in throwing at pence, which were placed on pieces of stick… with a piece of iron”9 and is also referred to in 1311 as halfpenny prick10, which indicates a certain inflationary trend before another mention in 1419, when the London Liber Albus decreed that “no man play…for silver at no unlaufull game”, citing ‘coytyng with horsshon’ (quoiting with horseshoes) and ‘penypryk’. A missile in penny-prick could be anything – iron, as we said, but also throwing a knife at the penny on a peg was common.

We can take an obvious diversion here and note the use of the word prick – which means in several dialects, and in the occupational jargon of thatching, a peg, i.e. a sharp piece of wood; and used more broadly, anything sharp or pointed, like a thorn or splinter, the origin of getting your finger pricked. And the association of this dialect form of peg with the slang for a certain male body part is self-explanatory and unnecessary to explore further here!

So we have a description of pennyprick, of throwing missiles at – rather than in quoits, near – a penny balanced on a prick of wood, presumably trying to knock the penny off and equally presumably winning the said penny. The same sort of game, played with stones instead of something sharp, is pennystone. And it was popular enough in the northern parts of Britain to leave its mark in language and landscape.

My personal discovery of the game of pennystone (though not ground-breaking, since it was well enough known to anyone reading the right material, it was instructive in not taking the words of predecessors too much on trust, especially in folklore) struck a chord as soon as I came across it, because after all, the pennystones at Midgley and Wainstalls were said to have been tossed over the valley by Robin Hood. The surviving folklore doesn’t say why, but other folklore does offer an explanation.

Robin Hood in 15th century woodcut

Robin Hood in 15th century woodcut

It tells us that Robin Hood was very fond of a game of quoits or its variations in the north country, and particularly the South Pennines; because it wasn’t just the two Pennystones he is reckoned to have played with: Standing Stone, on the Mytholmroyd-Sowerby road, used to stand in the road outside Bull Green House (which is why it isn’t there now), and was described by Watson as “a rude stone pillar, near six feet high” which Robin Hood “is said to have used … to pitch with at a mark for amusement”11, obviously referring to a solo game of pennystone. And from Blackstone Edge, between Halifax and Rochdale, he threw a great stone six miles into Lancashire, leaving incidentally the imprint of his two fingers and thumb on it, which landed at Monstone Edge and is now called Robin Hood’s Quoit12. It wasn’t just the north, either: Robin Hood’s Butts, in Somerset, are barrows about a quarter of a mile apart, with small depressions in their summit; an 1818 report quoted a local’s attribution of these bowls – “Robin Hood & Little John undoubtedly used to throw their quoits from one to the other; for there is the mark made by pitching their quoits”13. Meanwhile, ‘quoit’ is a frequent element of megalithic place-names, such as Lanyon, Chun and Zennor Quoits in Cornwall, and Pentre Ifan in SW Wales; the quoit here referring specifically to the capstone of a dolmen, but in practice applied to the whole monument.

And so we can deduce that pennystone was a game sufficiently well-known in the Pennines for local legends to grow up citing it, confident that hearers would know what pennystone meant. But time moves on and not all hearers did get the reference; at some point, through prohibition or natural wastage, pennystone grew to be unfamiliar to the early bourgeois antiquarians who laid the assumption with plague traditions, and subsequent writers who took them at their word, and more recently some have seen pennystone as a precursor of a more recent and slightly different Northern traditional game, brassies14.

And we know now that Plague Stone and Penny Stone are not synonymous, and when we come across a Pennystone somewhere, it might just refer to exactly what it says – the bygone pastime of pennystone.

Notes

- Rev. John Watson, The History of the Town and Parish of Halifax, Milner, Halifax, 1789, p.17.

- Which is what the local Halifax historian Crabtree said in 1836 about the Wainstalls Pennystone, though a 1964 excavation by Varley and Gilks found no evidence for such a circle, and Watson’s compendious History of Halifax made no mention of the circle, while referring to the pennystone folklore. ‘A Stone Axe-hammer, Robin Hood’s Penny Stone & Stone Circle at Wainstalls, Warley, near Halifax, West Yorkshire’, Raymond A Varley, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal 69, 1997.

- Jessica Lofthouse, N Country Folklore, p.202

3a. Thomas Brayshaw & Ralph Robinson, A History of the Ancient Parish of Giggleswick, Halton & Co, London, 1932, p150.

- Lofthouse, p.202-203

- John Hislop, An Explorer’s Guide to Penistone & District, Penistone & District Community Partnership, 2006, p.8.

- Halifax Guardian Historical Almanack, 1913, pp.82-83.

- J Harte, pers. comm. 2008.I am grateful to Jeremy for helpful discussions, as ever.

- Joseph Strutt, Sports & Pastimes of the People of England, 1801; pub. Methuen 1903, repub Firecrest, Bath, 1969, p.63-64.

- Strutt, p.312.

- http://www.pbm.com/mailman/listinfo/hist-games

- Watson, p.17.

- Henry Fishwick, The History of the Parish of Rochdale Clegg, Rochdale, 1889, p.538. John Roby, Traditions of Lancashire, Vol.2, L Heywood, Manchester, n.d., p18.

- From The Gentleman’s Magazine Library, ed. G L Gomme, Elliot Stock, London 1885, p.88, with thanks to Dave Smalley.

- According to an undated pamphlet produced c1980s by the Northern Traditional Sports Association. Brassies involved a pair of stone discs about 4″ in diameter, similar to those used for another local pastime, road bowls. Iron and brass discs were sometimes used instead of stone, and the game involves casting into circles rather than at a mark.