John Billingsley shares a site that once offered – and may yet – a unique but vulnerable glimpse into the prehistory of North Africa, and local serpent worship

The ancient site of Slonta,1 in NE Libya, is one unlikely to be seen by western tourists for some time to come, if ever. I was lucky enough to see it in 2010, on a guided tour a year before the rising that toppled Col. Gaddafi. The tour was ostensibly for the magnificent Roman and Greek remains in the country, like Leptis Magna and Cyrene, but at my request the guides made a special excursion to this small but remarkable indigenous sacred site, which I had only heard of a few days before through exhibits at the Jamahiriya Museum of Libya in Tripoli.

When we arrived, it was unimposing – a rusty notice, a locked gate, and a chain-link fence around it which was easily scaled by the tour guides, who, despite the lock, opened the gate from inside! It was clearly off the map as far as its official status went, though it had been restored in 1993 following collapses caused by heavy rain.2 For the same reason, there must surely be concern over its survival through not just the civil war, but also the activities of post-Gaddafi Islamists – especially as the remains contain copious human and animal imagery likely to date from pre-Islamic indigenous Libyan Berber culture.

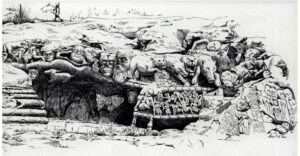

Slonta is in the village of Aslanta Lasamisis, in the province of Cyrenaica, about 40mls from the Hellenic city of Cyrene; the ancient village lay on routes between the interior and Greek settlements, including from Derna to Berenice (modern Benghazi). The site is situated near a spring in an area of limestone. While its original date is unknown, a central column base indicates some Classical influence at some stage in its history, though there the Classical resemblance ends. Part of the site is a low cave, more of a recess, which was once enclosed in a space that may have been a larger cave now collapsed, or a roofed structure (See Fig.1 for a reconstructive impression, and Fig. 1a for site as it appeared in 2010), perhaps best called a grotto. It is assumed to have been a Berber funerary site.3 However, its Arabic name, El Tesuira, means ‘picture gallery’, and gives a clue to the site’s unique characteristic – a panoply of imagery that is thought by many, despite indications of Greek influence in the column base and discovery of Bronze Age coinage, to be a unique record of Libya’s pre-Greek culture. Libyan archaeologists in the 1990s, however, concluded it dated from the 2-4th centuries CE on the site of an earlier temple to a serpent divinity stretching back to the 4-5th century BCE.4

Fig. 1 Reconstruction (after J-C Colvin)

Fig. 1 Reconstruction (after J-C Colvin)

Fig. 1a General view in 2010

Fig. 1a General view in 2010

The principle image depicted is a giant snake, which according to the Museum explanations is thought to be a native Libyan totem; its remains can still be seen in what was presumably once the north side of the grotto (Fig. 2). Pliny the Elder remarked in his Natural History that the prehistoric Psylli tribe were thought to be immune to snake bites, as well as having the ability to counteract the venom; the immunity (and presumably healing skills) derived, it was said, to their custom of exposing babies to poisonous snakes.5 Over time, I guess that is indeed likely to produce immunity through those that survived bites… Descendants of the Psylli still lived in the area in Pliny’s time.

Fig. 2 The great serpent (after Haimann 1886)

The snake was clearly ascribed significant cult status in Libyan prehistory, and the indigenous snake goddess is thought to have been called Lamia6 (which was also the name of a Libyan queen famed for her beauty and cruelty). The Gorgon Medusa – she of the serpent hair and the petrifying gaze – seems also to have originated in Libya and was probably modelled on Lamia (or her mythical reputation); this way, the story of Perseus slaying Medusa becomes a Greek narrative of dominance, which simultaneously emphasises the fearsome nature of the ‘other’. Greek myth also links the legendary beauty with the horrific transformation by alleging Athene turned Medusa into a snake-haired monster after she slept with Poseidon in one of Athene’s temples. Wikipedia has it that “The 2nd-century BCE novelist Dionysios Skytobrachion puts [Medusa] somewhere in Libya, where Herodotus had said the Berbers originated her myth, as part of their religion“.7 The Medusa’s reputation spread widely and lived long, largely through the use of her image as an apotropaic device on Greek shields and pan-Classical buildings; 70 Medusa masks were found in the Severan Forum in the magnificent Roman city of Leptis Magna on the Libyan coast, perhaps underscoring her local reputation (Figs 3 & 4).

Figs. 3 & 4 Medusa inthe Severan Forum, Leptis Magna

Around the snake and scattered all across the walls of the grotto and outside are an astonishing number of other carvings (Fig. 5), mostly human, including several bodiless heads (though this is referred to as the ‘severed head’ motif, there is no indication that the heads shown are actually severed, as such), and animals such as pigs – one other local name for the site is the Pig Grotto (Fig. 6 & 6a) – cattle (Fig. 7), a lion, and probable (in view of the degradation of the carvings) deer, dog, crocodile and horse. Several of the human figures close to the snake may be interpreted as making offerings or prayers, reaffirming the assumed divine status of the serpent.8

Fig. 5 Carvings in the grotto

Fig. 5 Carvings in the grotto

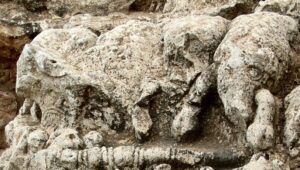

Beside the inner recess, one group of four beasts is generally accepted to be of four pigs or boar (note that one of Haimann’s sketches in Fig. 5 depicts one of them more like a big cat, while his other sketch shows damage already occurring). The barred base they stand above may be a table, and a crowd of humans are in attendance, apparently themselves on some kind of dais with legs (See Fig. 5), leading some to interpret it as a sacrificial feast event;9 yet the animals seem possibly aggressive and some of the people decidedly uncomfortable, so others prefer to interpret it as an attack by the beasts. There is, alas, insufficient basis for any reliable inference, and without comparable sites of that period a definitive answer will be elusive.

Figs. 6, 6a

The swine relief, 1880s & 2010

The swine relief, 1880s & 2010

Fig. 7

Fig. 7

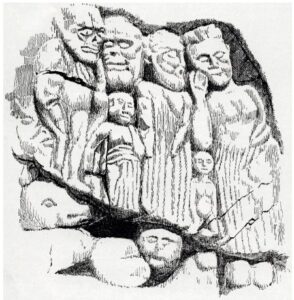

The multitude of human figures – both male and female, adults and children – present a motley range of characteristics and raise similarly unanswerable questions of interpretation. Some hold their hands above their heads – is this a mourning gesture, or an honorific one, or a gesture of fear? Lendering sees fear in many of the postures and expressions10 – if this was a shrine to a petulant snake goddess, would such interpretation be explicable?

Many figures are pressed together in close conjunction, even talking slyly to each other, rather similar to figures in some of Europe’s Gothic cathedrals (Fig. 8) – could these be in a procession, or an attendant crowd? Some of the male figures appear to be naked, such as the figure at what may have been the entrance to the grotto (Fig.1a; note the snake behind sliding towards the innermost recess).

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

Fig. 9

The ‘severed head’ motif is also strongly present, most strikingly at arguably the most liminal part of the sanctuary, the entrance to the recess (Fig. 10); they show striking similarity to archaic heads found across Europe.11

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

The volume of figurative carving here in this tiny, evidently sacred, space is overwhelming; everywhere you look, it seems there is another figure, or a face peering out, or an animal in some posture, or some sort of vignette being performed, or something that is so deteriorated it is impossible now to make out, but which is obviously one more barely penetrable layer of imagery. Interpretations are many; answers few; puzzlement and wonder almost infinite!

The evident deterioration of the carvings between Haimann’s visit in 1886 and my photos in 2010, and the fact that the sanctuary is carved out of limestone shows that the site, once excavated and restored, should have been kept under cover and protected from both elements and vandalism (though admittedly that would probably have meant I would never have been there to marvel at this unique site). It would be interesting to know how this and other Libyan sites (Gaddafi parked military vehicles inside the Leptis Magna ruins) have survived the conflicts so far; and if Slonta, the only known Berber sanctuary of its kind, has been lost, it is a loss to humanity.

Notes

Line drawings after: Giuseppe Haimann, Cirenaica (Tripolitania) Disegni presi da schizzi dell’autore, Milan, 1886. Other images John Billingsley, 2010.

- Recorded as Salantah on the Geological Map of 1977. E. Edward Tawadros, The Geology of North Africa, CRC Press 2011, p390.

- Muhammad, Fadhi Ali. Aslonta Temple. General Authority for Tourism & Handicrafts, Tripoli 2009

- www.temehu.com/Cities_sites/slontah.htm, acc’d 19-1-19.

- Jona Lendering, www.livius.org/articles/place/slonta/, acc’d 19-1-19; Muhammad 2009, p.31.

- Lendering, www.livius.org/articles/place/slonta/; https://www.temehu.com/Cities_sites/slontah.htm

- Barbara G Walker, The Woman’s Encyclopaedia of Myths & Secrets, Harper & Row 1983, p.527.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medusa, acc’d 19-1-19.

- Muhammad 2009, p.26.

- Muhammad 2009, p.21.

- www.livius.org/articles/place/slonta/

- See John Billingsley, A Stony Gaze, Capall Bann 1998.

Published in NE156, March 2019, pp.17-21 https://northernearth.co.uk/subscription/

Following: Update

A Middle Eastern Serpent Goddess?

John Billingsley wonders if he can spot parallels between ancient carvings in Libya and Palestine

Too often we run news articles about prehistoric remains being defaced or destroyed in the name of Islamic religious bigotry cancelling pre-Islamic cultures (in the same way as our own Christian, especially Protestant, fundamentalists have done to UK heritage). So what would ISIS and Taliban mentalities have made of a head dug up by a farmer in Gaza, Palestine? The 9″ limestone head is crowned with a snake ‘crown’, and is locally said to be a representation of the Bronze Age goddess Anat, dating to about 4500 years ago. Some countries, following Egypt’s long-standing example, are increasingly recognising the value of archaeological and historic depth in their own sense of self, and the words of the farmer who found it are welcome: “We thank God, and we are proud that it stayed in our land since the Canaanite times”. The director of Qasr el-Basha museum, where it is now displayed, echoed the point: “This is the Palestinian people and their ancient Canaanite civilisation”.1 As Hamas, Palestine’s militant rulers, have their own history of destroying Canaanite remains and ancient Greek artefacts, this may be a hopeful sign; of course, it cannot be seen separately from Gaza’s own political predicament in the Palestine-Israel contestation.

Anat, also known as Anath, was a Canaanite/Semitic war goddess known for her fierce temperament and also for her role in freeing the god Ba’al from the underworld. She was however not known for her affinity with snakes, as far as I have been able to ascertain, and indeed Ba’al was said to have especial enmity towards snakes, which further complicates any association.2

So the serpent’s-head cap would appear to me anomalous; does the Gaza figure really represent Anat? Or might it be more closely related to the figure depicted in the mysterious prehistoric Libyan site of Slonta?3 There are potential similarities between the Gaza image and the face at the head of the snake at Slonta, though the Gaza image is ‘crowned’ by the snake whereas at Slonta it is vice versa. Or might the two be avatars of each other, sharing certain attributes of a Middle Eastern Bronze Age conceptualisation?

The Slonta figure has been identified locally (tentatively, owing to the site’s uniqueness) as an indigenous Libyan Bronze Age queen called Lamia.4 Her biography looks a little more promising, though unpleasant. As she had had a relationship with Zeus, Hera killed her children. Unable to exact revenge on the gods, she took it out on human children (an attribute inherited by the malevolent Greek demons also known as lamia) − the beautiful woman she was became a hag, and a “shape-shifting snake with a woman’s head”.2 Lamia also became associated with Medusa of the serpentine hair and petrifying gaze, who may have originated in Libya and may also be an avatar of Lamia. Prehistoric Libya appears to have accorded significant cult status to the snake, and at Slonta several human figures appear to be making offerings to the serpent. The central serpent and head composite design is oriented dynamically towards a dark cave populated with disembodied heads, quite possibly an underworld allusion.

At this remove, there is only so far such speculation can take us; but in my view, though no Palestinian academic is likely to hear it, insights into this new-found Gazan cult artefact may possibly be gleaned from Libya rather than Anat’s heartland.

Notes

- Times, 28-4-22. Smithsonian Magazine 9-5-22, www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/palestinian-farmer-digs-up-4500-year-old-goddess-sculpture-180980055/.

- Standard Dict. of Folklore, Mythology & Legend, Funk & Wagnall.

- John Billingsley, ‘Riddles in the Land of Medusa’, NE156, March 2019, pp17-21.

- See, e.g. Robert Graves, The Greek Myths 1, Ch.61, who does suggest in passing a link with Anat.

Published in NE170. December 2022, pp.24-25