Cognitive maps and other inherited understandings can illuminate historical landscapes with a phenomenological focus

The presence of memory accretes to locations – not for nothing do we describe places as ‘our familiar haunts’, for at any one time a place is composed of layers of itself. It haunts itself… from what we see now, to what we have seen in the past that lingers like a ghost in the memory, and to what others have done to the place in the more distant past – manifestations, often ruinous and fragmentary, of its own spectral memory. Such investigations and subsequent explorations lie at the heart of alt-antiquarianism, which embraces not just archaeology but folklore and human experience of liminal events. Anecdotal evidence is nonetheless still evidence when examining how places work and our synaesthetic responses to them.

Through our particular lens, we see the legends and connotations attached to specific places as manifestations of people’s interpretations of those places – through later stories and placenames, or through the other end of the telescope, such as allowing stories and placenames to suggest how previous generations saw these places. Take Tuel Lane in Sowerby Bridge, for example – a very ordinary road, as you see. So what made people link The Devil – from which Tuel is derived – with this road? We may have lost the legend, but the name remains to speak of past associations. Similar placenames abound. Such otherworldly or supernatural associations speak of the character of a place, the psychogeography of a previous generation and a previous culture that we may access, albeit imperfectly, through its naming.

Folklore everywhere declares that we humans and creatures are not alone on or in this planet. A bewildering array of entities are rumoured to live alongside us – elves, fairies, pixies, boggarts, hobs, lobs, trolls, brownies, spectres, etc. – and while there are local variations and preferences for nomenclature, they all display their own characteristics. It isn’t for us to question, patronisingly, the objective realities of these beings, but to listen to those who have affirmed their existence, and then assess at what level they manifest meaning and significance.

Tuel Lane, Sowerby Bridge

Our perceptions of those characteristics may tell us something about how people felt about a place which namechecks such entities. We have to see them as metaphors for the place that bears their name. Tuel Lane, for instance, suggests a certain dark potential. Or take some fairly common placenames – Fairy Hole, Boggart Hole and Hob Hole. You don’t have to subscribe to Victorian literary misconceptions of fairies to appreciate that we are talking of places that are essentially different in character and kind. A broadly coherent set of locales tell us where such beings are customarily perceived. Fairies versus boggarts, for instance: You would be best advised not to have much to do with either, but boggarts are generally that much tricksier and – at best – mischievous than fairies, while hobs had their helpful side. Look, typically, for fairies in dells – like Healey Dell in Rochdale – for boggarts under bridges and stones, on moors and in dark places, like Manchester’s Boggart Hole Clough once was, and for hobs near where people dwell, such as Hob Hole Cave at Runswick.

The placenames tell us – and the people who knew the names in their district – something about the nature of that place, and an understanding which, by the act of naming, became implicitly agreed upon by the local community. Names and narratives, thus, are a key to local cognitive maps, the phenomenology of past generations who were more rooted in their landscape and familiar with its various ambiences: they offer what we might call loric archaeology, historical psychogeography.

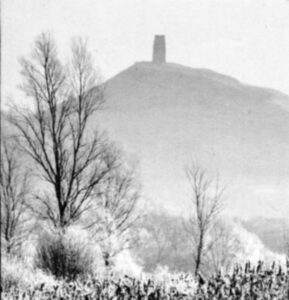

Place legends are, naturally, even more descriptive. Stoodley Pike is best known today as a 19th-century peace monument, an obelisk between Hebden Bridge and Todmorden incorporating Freemasonic principles. But the legends of the headland on which it stands predate the obelisk. And both past and contemporary place-lore and literary works about it have an under-narrative implying a local perception that the hill there is hollow – and inhabited.1 Like Glastonbury Tor is said to be a portal to the otherworld realm of Annwn, inhabited by the companions of Gwyn ap Nudd.

Or legends of otherworld entities may offer a warning. At Rothbury in Northumberland, for example, are two neighbouring hills, Lordenshaws and Simonside. The former is riddled with prehistoric remains and evidence of human activity – Bronze Age rock art and burial mounds, an Iron Age hillfort – but no significant folklore has been recorded from subsequent generations. Simonside, by contrast, has no prehistoric remains – but is characterised by legends of ann unpleasant tribe of supernatural being, the duergar, who presented a real threat to those venturing on the hillside, particularly at night. In other words, the folklore warns mortals off the hill. The question is why?; could it be just a dark and dangerous place, particularly at night? Were there some nefarious this-world activities going on which people needed to be scared away from? Or could it be the remnant memory of a sacred and tabooed place, proscribed for mundane activities, but alluded to in the ritual sites of Lordenshaws just below Simonside? The modern folklore, again, may be indicating an ancestral local psychogeographic sense.

By listening to the background hum of folklore we might, in Tilley’s words, “think in the same style” as communities that have preceded us, and perceive a dimension of common sense that is invisible in most history books. Folklore might help us to decipher what makes a place uplifting or sinister, or what makes it liminal or numinous, and how people maintain such perception over time. Place narratives allow us not necessarily history, but the chance to walk in the mindways of our ancestors. As Alan Garner commented “I don’t believe that happened, but I can show you where it happened”.2

Often, these otherworldly perceptions coincide: fairies and wights may be said to inhabit burial mounds – but so what? Well, when archaeologists dig into an ancient sacred site, no one is surprised if it suddenly teems with rain and turns the site to gloop, or someone gets hurt, or recovered artefacts seem to be somehow ill-starred. Even though actual attested events of this sort are far less frequent than the stories, the readiness for such narratives to take hold is telling in itself – about how people feel intuitively about our treatment of place, especially of places ‘stained by time’, as Mark Fisher describes it. Retribution is anticipated (see p.5, ‘Ancestral offence’). This is particularly true of old megaliths, barrows or churches, places of erstwhile ritual, but we also have cases in Scotland and Ireland where disturbing invisible lines of fairy passage will do no one any good.3 Spectral presences – visual, perceptible, auditory or olfactory – turn up where some dark or significant event has taken place in the past, and the place holds the memory until resolution is achieved. Violation or disrespect of a place may rebound or change the atmosphere of that place.

Alternatively, spend the night on certain hilltops, like Cader Idris, or at certain megalithic sites and you’ll wake up either a bard or bonkers, and maybe both. Funeral paths once known by names like Coffin Lane – invariably renamed and sweetened from the 19th century onwards because of changing sensibilities to the narrative of life – impacted on folklore. We may encounter hauntings, or the belief that the passage of the dead across ground hallowed that route as a public right-of-way, creating present-day paths that by dint of custom thereby link the mundane and the otherworld.4 Certain spots in the landscape encode experiences of a different world, of differing potentials within the same frame. Of geography reaching into the psyche. Portals into something behind a veil that, like the Neolithic cursus, occasionally parts at certain spots.

Familiarity with local folklore can give us a glimpse into the psychogeography of previous generations, as the novelist Alan Garner has demonstrated.5 This can in turn sensitise us to the ambiences once present. This is like a mutual underworld quest, and like all true underworld quests, the adventurer should bring something back to this world, this time. Perhaps it may be, as I say, a cautionary event – an experience that catalyses a placename or a legend that says in its own way ‘beware of this place’, or at least ‘don’t be surprised if something happens at this place’, ‘be aware that anyone you meet here may not be straightforward’. These things will persist longest, longer perhaps than an insight into what a place is good for – because don’t we all hold bad memories stronger than good ones?

With folklore and legends attached to locations we are pitched back again into the sense of land and nature as narrative, whether through natural instigation or human intervention. Archaeology came belatedly to the realisation that natural forms such as weirdly-shaped rocks may be of equal importance as built monuments. A simulacrum – perhaps a rock like a face or a horizon resembling a reclining figure – would not be lost on a synaesthetic imagination, and may present itself as a manifestation of a genius loci or anima loci or of a more patronal spiritual overlooker. Even if not seen as manifesting spirit, it could be seen as a point of imaginal reference allowing contact with such dimensions – another metaphor, and a crucial step in narrativising place. And human behaviour could be generated by such an association, leading to a tradition of votive deposits, and even, some suggest, the enigmatic abstract rock art known as cups and rings. As Richard Bradley observed, that is the point at which perception becomes visible in a standard empirical archaeological context: “the significance of a particular location becomes archaeologically identifiable through that activity, and yet there is every reason to think that the place itself had achieved special significance before”.6

The synaesthetic as well as psychic resonance of place lies, I would say, at the root of culture. In historical terms, how a place was perceived and then treated, referred to, developed, clues us in to the development of social structures in a process that eventually leads us to Debordian psychogeography, described earlier in this series.

Forteans and earth mysterians, artists and poets and novelists too, and certainly local traditional storytellers, were probably ahead of the archaeologists in this perception. Amateur researchers can’t hope to apply the same resources or scientific background to investigation that academics can – but when it comes to narrativisation as a way of understanding places of the past as well as present, we’re on more equal terms, and not bound by the unforgiving materialism of empiricism.

Notes

1.John Billingsley, ‘Stoodley Pike’, Northern Earth 153 (June 2018), pp.12-19

2. Q. in Clare Button, ‘See not ye that Bonny Road? Places, haunts and haunted places in British Traditional Song’, in A. Paciorek et al., Folk Horror Revival: Field Studies, 2nd ed., p282; from Celebration: Alan Garner: The Edge of the Ceiling, ITV 5 June 1980.

3. Paul Devereux, Fairy Paths & Spirit Roads, Vega 2003, Chap. 3

4. Devereux, 2003, esp. Chap.2; Haunted Land, Piatkus 2001

5. Alan Garner, By Seven Firs and Goldenstone: An account of the legend of Alderley, Temenos Academy 2010

6. Richard Bradley, An Archaeology of Natural Places, Routledge 2000, p.79

Published in NE160, March 2020, pp.10-13