Christine Rhone visits a little-known piece of London’s mystical heritage

No need to travel to Poland or Spain – the cult of the Black Madonna is thriving in NW London. Not just one, but two major shrines exist in the borough of Brent. The name of this recently created borough comes from the River Brent, after the Celtic goddess Brigantia. About a mile from each other, one shrine is Roman Catholic – Our Lady of Willesden (OLW), founded in 1931 – and the other is Anglican – St Mary’s Parish Church (SMPC), presumably founded in 938 and featuring an ancient holy well.

No need to travel to Poland or Spain – the cult of the Black Madonna is thriving in NW London. Not just one, but two major shrines exist in the borough of Brent. The name of this recently created borough comes from the River Brent, after the Celtic goddess Brigantia. About a mile from each other, one shrine is Roman Catholic – Our Lady of Willesden (OLW), founded in 1931 – and the other is Anglican – St Mary’s Parish Church (SMPC), presumably founded in 938 and featuring an ancient holy well.

There is a whiff of rivalry and obfuscation between them. At one time, the Catholics prominently featured the Anglican holy well on their website, but without giving its location. On my first visit to OLW, I fully expected to see it there. The holy water dispensed at OLW is not from a holy well, but is ordinary water that has been blessed. In reply to my query, a priest told me that OLW hopes to drill another holy well nearer to it, mentioning the etymology of the placename Willesden as ‘hill of the wells’ and fund-raising efforts. To be fair, both churches did take part in an ecumenical procession in honour of the Black Madonna in 1980.

The shrines possess three statues of the Black Madonna, two in OLW and one in SMPC (there may be more that I did not see). The main Madonna in OLW, carved in 1892, comes from an oak branch that grew in the churchyard of SMPC. The statue, whose skin and clothing are a deep caramel colour, stands high on a shelf in a separate Mary chapel amid a vast painting of foreshortened angels flying in a turquoise heaven. In 1954, which the pope declared a Marian year, parishioners carried this statue in procession to Wembley Stadium and crowned her in solemn ceremony before 800 pageant performers and 94,000 spectators praying rosaries together. Her travelling days are over, however. For security reasons, she is now fixed in place on her shelf.

The shrines possess three statues of the Black Madonna, two in OLW and one in SMPC (there may be more that I did not see). The main Madonna in OLW, carved in 1892, comes from an oak branch that grew in the churchyard of SMPC. The statue, whose skin and clothing are a deep caramel colour, stands high on a shelf in a separate Mary chapel amid a vast painting of foreshortened angels flying in a turquoise heaven. In 1954, which the pope declared a Marian year, parishioners carried this statue in procession to Wembley Stadium and crowned her in solemn ceremony before 800 pageant performers and 94,000 spectators praying rosaries together. Her travelling days are over, however. For security reasons, she is now fixed in place on her shelf.

The 1892 ststue of Our Lady of Willesden

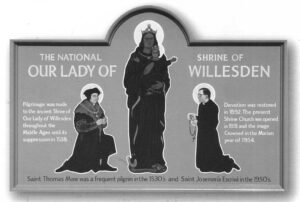

For processions, the church has a second statue of polyester resin made sometime in the 1960s or ’70s and painted a shade of burnt umber. This Black Madonna stands by the main altar for extra display during Marian months and on special occasions, such as the 50th anniversary Mass of the pilgrimage to Willesden of St Josemaría Escrivá, the founder of Opus Dei. A large painting beside the front portal of OLW shows this saint together with St Thomas More as regular pilgrims to the shrine, in the 1950s and 1570s respectively. More made his last pilgrimage to Willesden just a week before his arrest and ensuing execution (His pilgrimage was, of course, to SMPC).

The processional statue of Our Lady of Willesden

The SMPC Black Madonna, the colour of double espresso, is a big limewood sculpture by Catharni Stern. The Madonna is seated, holding the Christ child, whose arms are outstretched. Blessed by the Bishop of London in 1972, it stands prominently before the chancel and opposite the holy well, a modest garden-style fountain with a tap and basin. Visitors can freely take the water, which is also available in labelled bottles.

Otherwise, the two shrines are very different. The earlier one is SMPC by a good millennium. King Athelstan the Glorious gave ten manors to ‘Willesden cum Neasden’ in 938. This date presumably marks the founding of SMPC. The first written mention of the church dates to 1181. Tradition tells of an apparition of the Blessed Virgin in the churchyard. Pilgrimages to the church to see the Black Madonna and to drink from the healing waters – said to be beneficial for the eyes – appear on record by 1475, although they probably began earlier. The agents of Henry VIII entered the church in 1538 and removed the Black Madonna to Chelsea, where it was burnt in a great bonfire. Destroyed were images of Our Lady of Walsinghan, Ipswich, Caversham, Penrhys and others.

In punishment for having housed not just one, but two ‘idolatrous images’, SMPC had to pay an annual fine for more than 350 years. In 1902, the vicar stopped making payments. A small Madonna was reinstated some years later, superseded by the sculpture of 1972. In 1996, access to the holy well was moved from outside the church to within its walls.

The SMPC churchyard, an ancient burial site, has recently undergone a major operation to transform its formerly wild dilapidation of fallen tombstones and shrubberies into a tidy park. The stones and the dead no longer sleep in the benign neglect of dreaming grassland. By a busy roundabout on the way to Wembley, SMPC looks much like an English country church with hollyhocks and a 15th-century bell tower somehow surviving not far from central London. Its 1150 Norman baptismal font is one of the oldest in Middlesex. The well-trodden pilgrim’s route followed the Harrow Road (now the northern boundary of the Notting Hill Carnival route) and along Le Chercheway, now Church Road.

Until well into the 19th century, the church vestry remained the seat of all local government, providing relief to the poor, maintenance of the highways, law and order. A wall monument of 1913 commemorates the last survivor of the Company of Moneyers and their Apprentices, who struck coins in the Royal Mint, work done by several prominent local families. In the late 19th century, Prime Minister William Gladstone attended SMPC services regularly.

OLW is a Romanesque-style church in Harlesden that opened in 1931, a National Shrine for the Catholics of England. It has a strong Spanish connection. Land for the church, in an excellent location near the Jubilee Clock, became available after Fr John Mulcahy, parish priest from 1920-40, made a special pilgrimage to Lourdes to petition Our Lady for ground for a new church.

In 2008, I heard an OLW priest speak from the pulpit about the founding of the church in 938, but without mentioning that the date applies to SMPC, a mile away. I had doubts that many members of the congregation (if any) were conscious of this discrepancy. But in the words of Michael Dames, “Myth eats history”. And does it really matter? It may matter a bit, because accuracy here would indicate closeness between the Anglicans and the Catholics that some people might find uncomfortable.

The Anglicans had the original shrine, but the Catholics were first to restore the cult of the Black Madonna of Willesden. In the 19th century, great waves of Irish Catholics arrived in the parish, through immigration and the building of the railroads. Neighbouring Kilburn was said to be another county of Ireland. Masses began to be said openly around 1885 and at the turn of the century, parishioners were processing the Madonna through the streets, a practice ill-received by the locals. The Anglicans reinstated the cult of the Black Madonna in 1917. Today the Catholics enact a Black Madonna street procession every October. The Anglicans make a local pilgrimage to their own shrine in May or in July.

Many theories surround the history and provenance of the Black Madonna. Hundreds of such statues survive, mostly in S Europe. Some say that she is a descendant of the Great Mother goddesses like Isis, whose power is lunar and cyclic, encompassing both life and death. Her black colour is compared with the face of Kali, the Hindu goddess who dances in graveyards wearing a necklace of skulls and waving a sword. Others say that her blackness relates to the verse from the biblical Song of Solomon, “I am black, but comely, oh ye daughters of Jerusalem”. Only some Black Madonnas, however, have any other specifically African characteristics. Often, the sites connected with the Black Madonna are near sacred mountains and holy wells, as though bonded to the elements of earth and water (many will have heard of the Romany festival of Saintes-Marie-de-la-Mer, where a black statue of Sarah-la-Kali is ritually immersed in the sea). Still others say that the Black Madonna is simply a variation from the later Middle Ages, either sculpted in ebony wood from the East, or turned dark by time and candle soot.

The Black Madonna remains mysterious. While investigating her Willesden shrines, I had a strong intuition that an alignment (or a suggestion of one) may exist somewhere around them. Out of curiosity, I consulted Chris Street’s Earthstars. In the 2000 edition, the location of OLW falls within the area Chris calls ‘mark point 9’, which he simply labels “Church in Harlesden”, on his Horsenden Hill Axis. I later learned that his 2010 work incorporates SMPC as a markpoint on both his extended London Stone line and his Mary line of London.

Oddly, although the foundation of OLW is not ancient, the site for the church did apparently materialize as though in answer to a petitionary prayer. And while SMPC is ancient, it is located very near a temple of recent foundation, the Neasden Hindu Temple or Sri Swaminarayan Mandir, which housed a statue of Ganesh that apparently drank milk miraculously on 21 September 1995.1

Note

- On this date, the same miracle reportedly occurred simultaneously in temples all over the world, signifying the birth of a Great Soul…

Sources

Nicholas Schofield, Our Lady of Willesden: A Brief History of the Shrine and Parish, 2002.

Chris Street, Earthstars: The Visionary Landscape, 2000. (See p.74

Chris Street, London’s Ley Lines: Pathways of Enlightenment, 2010 (See pp.173,183)

K.J.Valentine, Our Lady of Willesdon: An Account of the Medieval Shrine, 1988.

Cliff Wadsworth (ed.), The Church of St. Mary, Willesden: A History and Guide, Willesden History Society, 1996.

Published in NE129 ((Spring 2012) pp.12-15