Arthur O’Neill recounts how a chance visit to an old church in the Leeds area led to an investigation into Tudor magic

We are very fortunate to have ancient churches because they preserve much of historic interest. I enjoy visiting village churches whenever I pass through a place new to me.

I was on my way to Fairburn Ings bird sanctuary a few years ago when I came across the ancient church of All Saints in Ledsham village, which is about a mile from the roaring traffic of the Al and to the N of Castleford in West Yorkshire. The church stands on quite a prominent mound and the village road has to squeeze round it, causing a fairly hazardous couple of bends for today’s traffic.

The church guide, published by the West Yorkshire Archaeology Service, says that it is thought to be the oldest church, if not building, standing in the county. It has, understandably, been the focus of much scholarly interest and the Journal of the British Archaeology Association has provided a forum for discussion on the architecture of the Anglo-Saxon doorway in the church tower1. In this publication, Dr. Faull discusses a previous article from another journal (which is proving very elusive to obtain), and before going on to discuss the tower doorway, quotes one Prof. N. Bailey, who believed that the carving of the imposts of the chancel arch could “be paralleled in seventh-century ecclesiastical work in Spain and France, notably at Jouarre. This suggests that the original stone church on this site was extremely early and of considerable importance, probably relating to a monastery in the vicinity. The two pieces of stone decorated with interlace work, now built into the north wall of the church, probably represent fragments of carved stone crosses from a cemetery associated with the Anglo-Saxon church”. The article then goes on to discuss how much of the doorway in the tower is original, after Curzon’s 1871 restoration, and how faithfully the Victorian masons copied the floral designs.

The suggestion of a very early monastery nearby seems to have been overlooked by recorded history. Close to the church is Ledston Hall Chapel, now part of Ledston Hall. It is thought that it was built at some time between 1170 and 1230, the former date being the martyrdom of Thomas Becket, to whom the chapel was and still is dedicated. The latter date is of a charter granted by the Priory of St. John the Evangelist, Pontefract. According to the pamphlet available in the church, Ledston Hall, Chapel of St. Thomas Becket, the charter “records an agreement between the Prior and Germanus the clerk, son of Adam the Chaplain of Ledston, who offers to surrender to the Priory a portion of land which he had from his father and promises that if made a priest he will ‘celebrate in the chapel of St. Thomas the mass for the dead in which they (the monks) are bound”‘.

There seems to be no mention of an earlier Anglo-Saxon monastery, as the evidence found by Professor Bailey would suggest.

The pamphlet mentioned above goes on to tell us that before 1066, Ledston had belonged to Earl Edwin Morcar, brother-in-law of King Harold. ‘Earl Edwin, the first lord (of Chipsech, Ledstune and Berewick) of whose identity we have any knowledge‘, lived at Ledstune. After his rebellion and death William the Conqueror gave the estate to Ilbert de Lacy. Then in 1092 Ilbert’s son, Robert, gave Ledston and half of Ledsham to the Priory he had founded at Pontefract. This was a Cluniac order imported from the monastic schools in Normandy.

It would seem the area had religious significance over a very long period of time. The Church guide, apart from telling us that the building begins in the late 7th or 8th century and much of the Anglo-Saxon architecture is still extant, mentions that “there is a re-used stone with a butcher’s cleaver carved on its surface. It is part of the side of a Roman Altar.” Perhaps the site is even older as a place of worship, but it is known that the Romans had found this area quite important.

A second pamphlet sent to me by the churchwarden2 says that a dig was carried out by Leeds University (no date given) which “established that Belgic settlers had occupied the high ground to the North well before the coming of the Romans… a catalogue of objects in a local museum c.1820 mentions among other things a Roman tile found at Ledston. From its characteristics the tile was adjudged to have been part of a tesselated pavement, of a kind used in connection with the headquarters of a Commander in Chief. Such evidence bears witness to Ledston’s role as a bridgehead at the northern edge of a long causeway on the important route to York”. Sadly the contents of the now defunct museum “have long since dispersed”.

There is, or was, a colliery nearby which was called Ledston Luck. It was alongside the A656, which appears to follow the course of an old Roman Road. When I enquired about the name I was told that when the pit first opened, the officiating dignitary wished the colliers luck and so it became part of the name.

This sounded a bit thin to me, especially as objects called ‘lucks’ (such as the Edenhall Luck) are known to exist, but I could find nothing other than the first story to account for the name in this instance.

I was also interested in the names of Ledston and Ledsham and wondered if there was a link with the nearby city of Leeds. In reply to a letter in which I posed this question, the churchwarden, Mr R Mathias, said that the names seem to be derived from “the region of Leodis”; the Old Boys Association for Leeds Grammar School is still referred to as Old Leodensians.

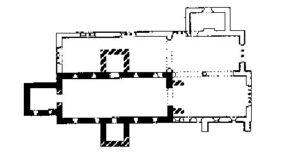

Ledsham Church

Ledsham Church in the early 8th century (from guidebook)

Ledsham Church in the early 8th century (from guidebook)

I was quite surprised, on entering the church for the first time, to see the amount of statuary on tombs, but then found that the church and incumbents had been given many endowments over the centuries from the local aristocrats in nearby Ledston Hall.

My eye was drawn to a table tomb in a dark northern corner, which had an unusual effigy. It was of a woman wrapped head to foot in folds of cloth, which I presumed was her burial shroud. At her feet was an even stranger object which I could barely make out in the gloom. It appeared to be a small representation of the upper half of a woman. The tomb belonged to a certain Lady Mary Bolles (or Bowles). The church leaflet gave her life history in brief and becoming interested I contacted Wakefield and Leeds reference libraries3.

Ladv Marv Bolles

Lady Mary was born in Ledston in 1579, presumably in the hall, and baptised on June 30th. Her father died when she was fourteen, supposedly by witchcraft from one Mary Pannal who lived in the village. Poor Mary Pannal was the last woman to be executed for witchcraft (at York, I believe), yet a nearby hill is named after her. Lady Mary was married twice and had two children to each spouse. She was awarded a baronetcy in her own right by Charles 1 in 1635. This was the first of only two instances where a woman was granted such an honour.

She lived through the Civil War, fulminating greatly when the Parliamentarian troops ‘requisitioned’ her bedding, but saw the restoration of Charles II before dying at the age of 83 on May 5th, 1662. She lived in Heath Hall near Wakefield for most of her life but retained an interest in Ledston. There is a seat in Ledston woods where it is said she often sat.

There were rumours about Lady Mary dabbling in the black arts, which would not have been dampened by the terms of her will. In this she requested that her bowels be removed and buried in nearby Kirkthorpe Church whilst the rest of her remains were to be buried six weeks later in Ledston Church. During this period she provided enough money for the provenance to keep together in one place all relatives, friends and servants, “and to that purpose all her fat beves [beef cattle] and fat sheep to be disposed of…” together with “…two hogsheads of Wine or more… and that several hogsheads of Beer be taken care for…”. She also provided £700 for “cloth Silke and Stuff for mourning for the gentlemen, and as much of the fine cloth as will make Cloaks only for the more ordinary sort, and as much of the Silke and Stuff as will make Gowns for the Ladies and Gentlewomen according to their respective Qualities”. She gave £400 to be spent on her funeral “and to all the Strange Poor who should come above 16 years of age, 6 pence apiece, and those under, 3 pence apiece.”4

Her remains must have been embalmed and I have no information where her body was kept during the six weeks or if indeed the terms of her will were carried out. There is a tradition, according to the church leaflet, that her ghost continues to haunt Heath Hall, with a suggestion that her wishes were ignored. She died in the White Chamber and it is said that she occasionally appears there and on a winding staircase that ascends to the roof. She also apparently flits along the coach road outside Heath Hall and in the adjacent fields.

Her shade appears in Ledston Hall too and those who have ‘seen’ her receive the impression of a “tall imposing figure in black, with a drapery drawn in folds across her breast”4. Apart from the colour this is rather like the effigy on her tomb. It was said that in order to lay her ghost a ‘familiar’ was carved in alabaster and placed at the feet of her effigy in order to hold them down.

Some say that the familiar represents Mary Pannal, which would be a delicious touch, but in all probability the figure is derived from the Witham family crest, which is described as “out of a ducal coronet a demiwoman, hair dishevelled holding in dexter hand a gem ring”4, which is remarkable in itself. The ‘familiar’ is considered as having been carved at a later date than the effigy, which adds fuel to the rumour of its intended purpose.

The original position of the table tomb and effigy was found to be quite inconvenient to a later incumbent, as it was within the communion rails. He organised some workmen to move it to a corner, whereupon “the church door opened unexpectedly, admitting a heavy gust of wind that blew dust round about the church for a few seconds – then all was still again”4. A second tradition avers that, “there was smoke issuing from her tomb and a sound of rattling”5. Notwithstanding, the table tomb was moved and now occupies a dim corner of the church.

Lady Mary seems to have been quite a character; yet if it wasn’t for her effigy, her memory would reside only in the dusty tomes of reference libraries.

There must be many such tales and legends woven around the life of our ancestors whose remains are remembered in stone and tablets in the time-capsules of our ancient churches.

Notes

- Faull, M L. The Decoration of the S doorway of Ledsham Church Tower’. Journ. Brit. Arch. Assoc. 139, 1986, pp143-147.

- Wheler, G. Ledston Hall, a Short History.

- Both staffs were extremely helpful, as was the churchwarden of All Saints and local historian John Gilleghan whom I contacted by e-mail. I am grateful to all of them for their help.

4 Taken from the church pamphlet, Lady Mary Bolles.

5 pers. comm, John Gilleghan

6 Peter Ryder, Mediaeval Churches of West Yorkshire, WYAS 1993

Published in NE87, Autumn 2001, pp16-20