Our series of self-guided walks continues with Aries (Mar. 22-Apr.21 approx.).

You will need the Ordnance Survey 1:25000 South Pennines map. Please note that routes and their condition were accurate at their time of survey, 2018-2020; updates may be made at later dates.

Please be alert to any other quasi-affirmations of Aries as you walk!

The Zodiac year begins in the spring, with the sign of Aries. This sign of the ram is ruled by Mars, and reflects its impulsive and assertive energy. It is worth recalling that the hills and valleys hereabouts were the cradle of the changes that brought about the Industrial Revolution, and drove it forward for better or worse; and that the driver of change was the wool and textile industry. Though the textile businesses are mostly gone, sheep are still to be seen on the hills – though it was not the wool of these hardy breeds that went into the local mills.

Lambs are familiar and welcome harbingers of spring in these dour valleys, but less familiar is the lamb of the Hebden Bridge terrestrial zodiac. It sits quietly upon Edge End Moor in Erringden all year round, turning its head to gaze behind its back towards the east.

In British landscape zodiacs, Aries is variously shown as a ram or lamb. The lamb with reverted head, as it appears here, is usually termed the Paschal Lamb, and is a symbol of Easter and of the Knights Templar; backwards-looking beasts are a very common feature in Celtic art[1]. This posture, thus rooted in our cultural heritage, is known from other landscape zodiacs, such as Glastonbury, Kingston-upon-Thames and Cuffley.

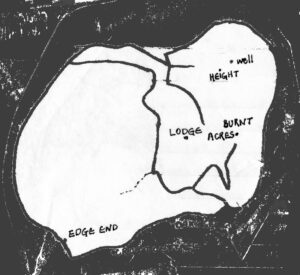

The Erringden lamb sits with a foreleg bent around Parrock Clough. The hindquarters are drawn in to the front legs. The haunch is a rough dome of moorland terrain; both here and the fields that comprise the rest of the figure are used as open grazing land for both cattle and sheep. It is about a mile from end to end, mostly marked in paths and trackways, with fields and earthworks assisting in detail. Some parts have become waterlogged and require care to remain reasonably dryshod.

The exterior lines of the Aries lamb are marked out in public rights of way, but some of these today have become waterlogged or otherwise troublesome. Nonetheless, they can be passed, and the most difficuult section of the walk is at the beginning. We need to summon up the headstrong Aries qualities to tackle the track that leads us on to the figure!

So we join the lamb by taking the footpath that turns left from the canal bridge by Eastwood sewage works. This first part of the walk is rather churned up and muddied by the feet of beasts – perhaps appropriately, as it is leading us on to the hindleg of the lamb. We are in Aries when a path enters from the right. The old path to the left has become a stream; climbing uphill beside it, we pass behind Oaks Farm.

In 1981, in the ruins of an old wall before the house, the tenants found an old carved stone head. Its crude features identified it as one of the archaic heads, often known erroneously as ‘Celtic’ heads, that are have been carved in the upper Calder Valley perhaps more than in any other part of Britain. How old the Oaks head is can only be guessed at; it may be Celtic, but the odds are that it is not. Oaks Farm, however, is a fine olf 17th-century house with a marvellous ogee doorway.

Further up the hill along the hindleg of the lamb is another ancient farmsytead; Cruttonstall was mentioned in the Domesday Book as Crubetonestun, and is one of the oldest homestead sites in the valley. Its name means ‘crooked farmstead’, but the present building is of a standard 18th century form. Recently used as a hay store, its present dereliction dates from a fire that destroyed the roof along with a thousand bales of hay. The blaze occurred on an apt date – March 20th, 1991, which just happens to be the beginning of the cardinal fire sign Aries. After Cruttonstall, we continue along the footpath, and the mound of land that is on our right is Edge End Moor, the haunch of the landcape lamb.

If we take the next footpath on the right, we will go along the edge of the lamb’s haunch, past Edge End farm and down through a corner of Callis Wood to join another trackway. We go to the right, along what is now the Pennine Way, but which used to be an old wool highway between Hebden bridge and Rochdale. The acorn symbol of the long-distance footpath takes us straight on where the motor track ends, but when it turns sharply left at a boggy stile, we pause.

Four paths meet here; straight ahead, the steep embankment runs beside the old wool highway for a time, but the bank predates the old route. It is in fact artificial – it is a deer leap, a relic of the boundary of the Erringden Hunting Park of Norman times. Here, however, the steep cutting seems to enhance the image of the backbone of the lamb, which it marks.

The Park was one of the recreational areas of the de Warennes, lords of Wakefield Manor. A number of placenames on the southern side of the upper Calder valley, as we will find in our zodiac walks, recall the old Park. Hunting parties, appropriately for Aries, were entertained at Lodge, which we shall pass in due course at the heart of the lamb. This was the most westerly part of the Hunting Park, and the boundary between the moor tops and the deer leap is marked by small standing stones. These can be identified by the ‘S’ (Sowerby) or ‘S.R.’ (Sowerby Ramble) incised upon them. Sowerby was actually a township on the other side of Cragg Vale, and these stones came to constitute an outlying ‘island’ of this township within Erringden. The Hunting Park, reserved for the sport of nobility, was highly unpopular with the local inhabitants, and when the last of the de Warenne line died in 1347, extinguishing the park rights, they hastened to tear down the palisades that kept them from the livestock that was -or should have been – an important part of their livelihood.

Our vantage point at the crossing of paths also affords us a clear view of Stoodley Pike, without doubt the major landmark of the upper valley. The site is of ancient notability, marked as a cairn on Jeffery’s 1775 map of Yorkshire and Carey’s 1794 map of England. The cairn was supposed to be the grave of a warrior, and responsiibility for its upkeep rested on the shoulders of the occupant of Stoodley homestead. If this duty were neglected, it is said that doors would bang and other poltergeist or boggart activity would occur. These were not the only mysterious happenings aspociated with Stoodley Pike. Flames or lights were also sometimes seen around the stones -indeed, its visibility for many miles around would make it an excellent beacon site – and another tale relates that in foggy conditions a door opens innto the hillside.

Despite this aura of strangeness, the site was chosen for the construction of a cairn in 1814 to commemorate peace following the Napoleonic Wars. Indeed, a human skeleton was found while digging the foundations, which lends credence to the presence of a burial cairn there. The foundation stone was laid with full masonic ritual, and blood was shed upon the site in an incident claimed to be accidental, but suspiciously reminiscent of traditions relating to foundation sacrifice; as Savage tells it, “a youngster perched on his father’s shoulder leant forward to see all that was going on, and was touched accidentally by the Tyler’s sword, and blood flowed freely”[4]. The 1814 monument was 113 feet tall, with 150 steps inside leading to a windowed chamber furnished with a fireplace, as if to keep up with the flames of legend. Standing at an altitude of 1300 feet, it would have been a fine and comparatively cosy vantage point for viewing the sun rise or set over the valleys and moors.

The strangeness of Stoodley was not yet done, however, for this monument to peace collapsed in 1854, on the very day that the Russian ambassador left London, signifying the imminent onset of the Crimean War. A replacement monument was in place, however, by 1856, and that is what we see today. At 120 feet, it is a little shorter, as well as slimmer, than its predecessor, and lacks both chamber and fireplace.

Our path, however, turns away from the heights, to the right and alongside a dry stone wall. We are still following the line of the haunch. The depth of the track indicates long use, and it takes us through to Higham. From here we can see how different in character the front and back of the Aries lamb are; the rough terrain of Edge End Moor and the country we have been walking through contrasts with the fields of the rest of the body, through which we are next headed. The track continues downhill to Lodge Farm, the old hunting lodge, and becomes a new concrete road. This crosses the lamb’s bent foreleg at Parrock Clough (the name ‘Parrock’ means ‘sheep-fold’) and the clough and another gully visible across the field are the outlines of this foreleg. The road takes us almost to the foot of the hill, but at that point we turn left and go back uphill beside the dry stone wall and above Burnt Acres Wood. A track branches off to the left towards the ruined farmstead of Burnt Acres, a name which indicates the surrounding fields were claimed by burning off the woodland. This place-name occurs only once in the Zodiac, and it is apt that once again we should have the element of fire making an appearance in the fire sign Aries.

The track is running through the neck and jaw of the lamb[5], and to our left, between the track and the buildings of Higham and Lodge, we can see the line of the stream and field boundaries that mark the outline of this part of the lamb’s body. Our track meets up with another near Height Farm; the section to the left can be taken as the line of the lamb’s mouth, but we turn right and follow the track, through the lamb’s head, past the farm. Just after it turns sharply left, we can look over the wall to see a well trough, brimming with clear water. This is located almost as if to mark the eye of the lamb. This is the only place in the Hebden Bridge Zodiac where a notable feature occurs at the eye of a figure and it is entirely appropriate that this should be found in Aries, as this zodiac sign has a special correspondence with the head and eyes. It is also perhaps significant to note that folklore often credits wells with eye-restorative properties, though whether this can be true of Height’s well remains untested!

Beyond here, we come to the woodland of Stoodley Glen; at the top of the slope a dry-stone wall divides field from wood and outlines the head and shoulders of the lamb. The path along the wall will lead us back to where we began the walk, along the top of a precipitous slope; the views over the valley from here may not always be for the faint-hearted or vertiginous, but are a magnificent end to the Aries walk!

[1] Megaw, Ruth & Vincent. Celtic Art, Thames & Hudson 1990, passim

[2] History & Antiquities of the Ancient Parish of Halifax

[3] Joan Savage, Stoodley Pike, p.21

[4] Joan Savage, Stoodley Pike, p.21

[5] Along this stretch, when leading a gyuided walk of about seventeen people, a lamb detached itself from the flock and ran over to greet us. While its mother stood and bleated at a safe distance, it insisted on having its head scratched by the group. Such unsheeplike behaviour could, we felt, surely only occur on the Aries figure – and indeed, did not happen on any of the other zodiac walks!