(ill. Davina Ware)

In 1972, walking up Glastonbury Tor, I was talking with a chap who, like me, had just hitch-hiked into town. As we approached the tower, he started talking about leys, which he’d just read about. For some reason, the topic sparked off something inside me; the next day I headed home and telephoned Garnstone Press, to place an order for the books he recommended − The View Over Atlantis and The Old Straight Track. A lot has happened in the field since then, and as our other contributors have suggested, not all of it makes much sense; and working through tracks and UFOs and ‘energies’ and grids has brought me back to a simpler notion.

Let me put it hypothetically and simply. Imagine you are in a trackless landscape, and you need to go somewhere – not necessarily anywhere specific, just away from where you are, and hopefully somewhere supportive of livelihood. You may set off in the easiest direction – perhaps following a valley – and see where it takes you. You may have some inner urging or hunch. Or you may pick a point in the distance – most likely a high hill, since they tend to be the most visible points in a landscape – and decide to aim for that. Sometimes something in the heavens might provide a bearing.

So off you go, always orienting yourself on this target or maybe just following your senses if it drops out of sight, and aiming to minimise the journey and its hazards. So you try and keep to a direct route, and in time you get there, and hopefully find it satisfactory. Perhaps you return to where you came from, or you stay there, or you move on elsewhere, again picking a route from the trackless surrounds. You’re meeting other people along your journey, and you swap stories – news of settlements, of water and food sources, of how they travel through the landscape.

Let’s say you decide to stay at the mountain, because the land is good and fertile, the water clear, the climate acceptable, etc., and the animals you hunt seem to like it there too. But you have kin back where you started, so from time to time you visit them, and they visit you, and some join you. And other people hear there’s a settlement and good water, and head for it on their travels, because after all the mountain is a good orientation point.

When people reach your mountain they find that your people are giving thanks for locating a good place to live, and as it was the mountain that drew you there, it is the mountain that receives your acknowledgment, as well as being the nearest place to the heavenly gods, if that is how your people construe the world. But it’s a mountain, not the kind of place you visit every day, and not accessible to all, so your people have built a shrine at its foot among the community to ease the necessity of expressing gratitude and increase the regularity of tribute. These become your two primary holy places – the near, in the community, stands for acknowledgment in the now, and the summit receives the thoughts that are sent to another dimension. Travellers making a safe arrival customarily give thanks at the near site. A service infrastructure builds up around this spot.

The journey to your mountain or back and forth from your roots takes more than a day, so stopping places where again there is good water and shelter become known and established, and the journey becomes refined to take the most direct route. Sometimes you need help ascertaining the way, so markers or series of them have been established to direct passage through these uncertain passages. Over time, a route will become composed of short sections oriented to different intermediate markers, and will interact with other journeys. Where such tracks old and new intersect, perhaps someone might settle at the cross-roads, a venue for trade, information and refreshment – the beginnings of another service infrastructure.

Some travellers are by now, for various reasons, orienting their journeys on ‘your’ mountain and its welcome, via these convenient nodes en route, building up an infrastructure of routes, stopping places, crossroads and settlements, both temporary and permanent. Mark-points have been appearing along the trails, and little shrines springing up, sometimes associated with a visible but distant destination, sometimes with the departure point, sometimes with the place itself, and sometimes just for the sake of safe travel. Frequently these stopping points are at springs or wells, sheltered spots with a secure ambience, or high places where the route can be seen more clearly – and sometimes they are at cairns and mounds, for some travellers will die on the road and must be buried according to custom and materials available. Some are remembered and visited by later travellers. These mark-points were significant places. The significance and meaning that builds fosters the sense of the sacred, the pattern underlying human existence.

Gradually, as the years and centuries pass, and more people travel between communities or places where certain natural resources are available, these scratched marks of passage over a trackless landscape – desire paths as we might call them now, the shortest feasible routes linking a variety of places and settlements that we want to go to – develop into a network of established routes. The underlying character of this ur-network is a web of straightish tracks, because they make better sense than circuitous wandering.

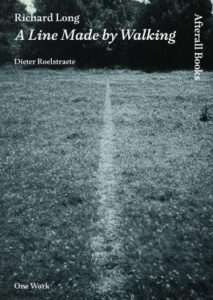

Straightish is probably the best we can hope for, because in practice “journeying on foot ‘is never merely a matter of getting from one point to another'”1 – obstacles have to be steered round, and wayfarers need to gather provisions on their way, and they can’t expect the requisite flora and fauna to await them in their path. So the line of passage inevitably goes for a little wander before returning to the line sighted on the next markpoint – like the cover of Watkins’ The Ley Hunter’s Manual implies (see p.8).

This sketch should outline a scenario familiar to those leyhunters that still apply Watkinsian principles, and it suggests that aligned trackways arose from simple wayfinding habits. Today, we would call such patterns desire paths or lines, and are most familiar in urban and local settings. Think of a church – the religious and social hub of a community, and the most visited building in the mediaeval village. Why, then, are so many paths – trackways and corpseways – aligned on churches? Maybe because they’re the quickest way to a much-frequented place? And perhaps because the church tower is the most visible thing in the landscape, and easier to walk straight towards. The micro-scale of the modern desire path illustrates the pattern of development of any straight track, including the macro-scale routeways that originated in the distant past and which we often now study as leys.

This is what artist Richard Long had to say: “[Watkins] is fascinating. I’m not not interested in all that stuff, but it’s just not where my work comes from… lines are the easiest thing to do, in the wilderness. You go from a stone, to a bush, to a tree, to a rock, to something on the horizon. It’s all about alignment. As a human being, I bring them to the landscape…”2

* * *

Were the people of this ur-network of routes following innate energies in the land? Probably not – they followed something far more reliable, their eyes. But you never know. In the early days of antiquarian dowsing, after reading Guy Underwood3 and about energy lines in The Ley Hunter, etc., I took my rods and pendulum out and about in the Colchester area, where I lived. I found that some of the most powerful Underwood-style spiral ‘blind springs’ occurred at the main entrances of Woolworths and Tesco. Of course, the chancels and altars of churches returned strong responses (but sadly Woolworths trumped St Botolph’s Priory). Other powerful responses, interestingly, came from the desks where friends who were writers and artists worked.

Mulling over these responses, it began to seem, to me at least, that where people concentrate their thoughts or passage, it seems to leave a trace that dowsing can pick up on. As earth mysteries plunged into the energy line debate, I began to wonder whether we weren’t putting the cart before the horse. Then I heard in the 1980s of Dragon Project experimenters mentally projecting a ‘line’ randomly across the King’s Men circle at the Rollright Stones. A number of people were then asked to dowse for any energy lines, and to place a small wooden marker where they got a response. Afterwards, Paul Devereux told me, “it was dramatic to see how about 70% of the markers clustered along what we alone knew was the thoughtform line”.4 As the energy debate moved through an increasingly Byzantine, even Borgesian, array of constructions both local and global, the question of ‘what came first’ became both more relevant and less addressed.

I came to think that in general, and in themselves, the old straight tracks and the networks that we, from Alfred Watkins to Graham Robb5 and ourselves, might uncover really aren’t anything esoteric or that much out of the ordinary, except in that they are vital arteries in the ongoing and necessary human relationship with the sustaining Earth, and our economic and political relationships with each other. They likely came about as secondary not primary phenomena in the same way that we cut a corner by walking straight across a greensward on the way to the shops, creating a desire line that others help to make into a path.

And I have come to suspect that any energy these older long-established tracks have, anything that can be dowsed or intuited along these old tracks, is also largely secondary, a residue from the emotions and presences engendered by frequent passage. Here we might consider an extension of the concept familiar in the science of magnetism, remanence; in our case an imprint following protracted usage rather than a quality or energy inherent in the place. Remanence can relate also to the place-memory hypothesis of some psychic researchers. My experience in Colchester and the Dragon Project’s thought-line experiment suggest that usage and directed attention have the potential to leave a trace. It’s a similar idea to magic or visualisation – an action done with will and directed attention will have an effect. Route-making fits the criteria.

This is no more mystical than life itself. Energy, ephemeral term that it is, with no intrinsic meaning, is a secondary interpreted phenomenon arising from our activities, our imaginations and our inner leanings – something we impart to (or take away from) a place simply by being there and acting upon it. It is all around us, not constrained in straight lines, but concentrated at points – not pearls on a thread, but more like dew drops on a web.

And that’s why in my opinion we should take our old friend Alfred at face value; but go back one step from his basic trackway notion to the idea that they were rudimentary desire paths, a natural disposition when no other path was available. Leys today have become like variety packs of highly-flavoured potato crisps, where even the flavours are cooked up in the imagination. Alfred Watkins would have preferred plain crisps, I feel. Plain crisps are closer to the real nature of the potato, and to desire.6

The cover to Alfred Watkins’ The Ley Hunter’s Guide; desire lines to remanence?

Alfred Watkins in the field (Davina Ware)

Notes

1. Tuck Po Lye, q in Tim Ingold, Lines: a brief history. Routledge 2007, p76

2. British Archaeology, Sept/Oct 2017, p12

3. Guy Underwood, The Pattern of the Past. Museum Press, 1969

4. Paul Devereux, pers. comm., 23-11-17 Published in NE164, June 2021, pp.26-29

Published in Northern Earth 164 (June 2021), pp.26-29