Our series of self-guided walks continues with Capricorn (Dec. 22-Jan.21 approx.).

You will need the Ordnance Survey 1:25000 South Pennines map. Please note that routes and their condition were accurate at their time of survey, 2018-2020; updates may be made at later dates.

Please be alert to any other quasi-affirmations of Capricorn as you walk!

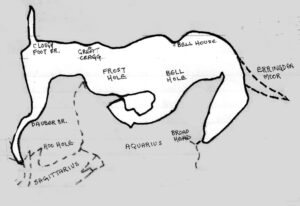

Capricorn is one of the more elusive figures in the zodiac, presenting two different potential outlines within the same area, and bearing the same posture. Our Capricorn is a butting beast rearing out of Cragg Vale on to Bell House Moor, tucked into the folds of the Aquarian eagle.

The first version to emerge from the map, in 1979, was a beast of stolid form, long in the hindleg, thick in the shoulders and neck, with a large head on Erringden Moor; the ‘ghost’ of a horn marked out by the official lines of paths on the map, but hard to find on the open moor itself, suggested a unicorn – a beast that does stand in for Capricorn in other British landscape zodiacs. By the time of the second complete circuit of the figures, in 1991-2, a slighter figure more like a goat with a shorter hindleg, long slim neck and small head with a hint of a small horn[i] lowered into Bell Hole, had begun to seem more likely, and by 2018 this was the option that was seeming to assert itself on the ground.

The ambiguity of form is mirrored in Capricorn’s celestial constellation image, too, in which it is a goat with a fish’s tail – an act of shapeshifting that derives from a myth of the god Pan escaping the monster Typhon by jumping into the River Nile, turning his lower parts into a fish. Perhaps there is an echo of that legend here, with Capricorn’s hindquarters in the Cragg Brook, and its head tucked into the wetland nature reserve of Broadhead Clough – if Pan were to be found anywhere, it would be here, so this is something we might look forward to at the end of the walk.

We start the walk at Dauber Bridge, on the Cragg Road just outside Mytholmroyd. There is a choice of routes here; the line of the Capricorn goat follows the Cragg Brook upstream, and you can choose either the riverside walk or the road walk. The decision probably rests on the seasonal conditions and weather – the riverside walk will inevitably have muddy patches, while the road also follows the river, if not as closely, but is dry and comfortable walking.

To access the riverside path, go up the concrete track from the bridge to a footpath post marked to Parrock Clough, and follow the sequence of paths up to Clough Foot Bridge.

By road, you continue up the Cragg Road to the footpath at Higher Clough Farm, and walk down through the buildings on a metalled track to the bridge. Here the riverside and road paths join, and we continue on up the lane. Where it bends to the right, the goat’s tail continues in the wooded space between the river and the field, extending to the next bridge at Spa Wood – the site, incidentally, of Cragg Spa, centre of Spaw Sunday celebrations on the first Sunday of May during much of the 19th and early 20th centuries, when people would come to drink the sulphuric waters of the spring, made more palatable by licorice.

The lane, which marks the goat’s back, follows a straightforward course up to Lower Cragg, when signs direct you off the motor lane and up on to the old footpath beside a stream – a lovely little path, but it can be muddy. It comes out (and rejoins the motor lane) at Higher Cragg. Note here the spiral carved on the stone quoin at the gate – traditionally a charm against fire.

From Higher Cragg the route becomes an earthen track again, still climbing steadily. When you reach two gates, take the stile by the wooden gate on the left, and continue on up. You will come to a gate, from which you can look back over your route, to Cragg Vale, to Mytholmroyd, and fragments of the Libra, Scorpio and Sagittarius figures, or across the valley beside you to Aquarius.

The goat’s back changes to shoulder here, and continues up an ancient sunken track, as directed by an arrow; however, the sunken track is blocked off by fencing, so though it’s unmarked by a yellow arrow, go through the gate and walk along the top of the track towards the farm you can see in front of you. At the end of the field is a stile, followed by a stream and boggy patch that you must cross towards the farm.

And so we come to Bell House, a place of some historical notoriety in a form that has more than a tinge of Capricornian correspondence in the sign’s close association with materialist activity. This was the home of David Hartley and his wife Grace, leaders of the Cragg Vale Coiners, and the headquarters of their local but nationally influential counterfeiting ring. For around five years, 1765-69, counterfeiting of gold moidore coins was proceeding at such a scale that even the national economy was affected – upper Calder Valley people had probably never seen so much gold, and despite brutalities and murders, the gang had considerable public support. The man responsible for ‘minting’ the gold, David Hartley, received the sobriquet ‘King David’, but ended up at the end of a rope in York; this ‘king’, who presided over a highly Capricornian operation, came to rest in Heptonstall churchyard, in the royal sign of Leo.[ii]

From Bell House, take the concreted track and shortly branch off on a footpath to the right; this takes you towards the moor, above the cwm-like wooded depression of Bell Hole.

At a marker post, you have another choice; a sunken track leads off to the left, and this would form the neck of the more stolid horse-like figure, stretching up to a meeting of tracks on the open moor where a right turn will begin to draw the head. If you prefer this version of Capricorn, take this sunken path – but it peters out in a hundred yards or so, so you will have to follow the line until you may catch a path leading off to the right (on the moors, paths on the ground do not always match paths marked on the map), towards the field walls you see in the distance, and then back across the rather boggy moor towards the top of Bell Hole. Accuracy to the outline is not essential, of course, and looping across the moor in this vicinity and returning to the top of Bell Hole will certainly see you in the head of this alternative version of Capricorn.

But as I have suggested, a more sprightly goat-like figure appears to be taking prominence on the ground, and if you are following this figure, then note but ignore the sunken track and follow the path on as it rounds the tip of Bell Hole; as it does so, you are following the goat’s neck, and you come to a post marking a footpath down a steep slope into Bell Hole. This is where the goat’s head begins, belligerently lowered into the woody hollow. Follow the path down and around, and you are walking in the delightful wetland nature reserve of Broadhead Clough. If Pan should be found anywhere in the Zodiac, this, I feel, is one if the likeliest places – and appropriate, too, for a goat-footed god.

The stretch of path from the moor to the markpost offering a choice of routes is contiguous with a wing of the Aquarius figure, which veers off to the left here; our Capricorn path continues straight on, with the stream close beside us, and where the stream comes closest to the path is the tip of the goat’s nose. From here on the line of the foreleg and the belly are the same, following the path through Frost Hole – another appropriate name, perhaps, for the first of the winter signs – though the belly, as with the hindquarters, prefers to follow the stream down towards Cragg Vale. Exiting the wood, however, the track straight ahead roughly follows the same line, and you follow it until you return to Dauber Bridge.

First published on this website December 30, 2023. Please refer back to main article: https://northernearth.co.uk/walking-myth-into-place-the-damned-zodiac/

[i] Horniness of some kind is certainly implicit in the vicinity: in Benjamin Myers’ novelisation of the Cragg Vale Coiners, The Gallows Pole, the lead figure of David Hartley is driven by a vision of strange supernatural stag-headed men on this stretch of moorland, and he told me the idea came not from his own imagination, but from an informant whose mother had seen such figures on the moor [pers. comm. 2018].

[ii] See Steve Hartley, The Yorkshire Coiners: The True Story of the Cragg Vale Gang (Amberley 2023) or John Marsh, Clip a Bright Guinea: The Yorkshire Coiners of the 18th Century (Robert Hale, 1971) for a full treatment of the Cragg Vale Coiners.